Meu SciELO

Interface - Comunicação, Saúde, Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1414-3283

Interface (Botucatu) vol.5 no.se Botucatu 2010

Collective welcoming: a challenge instigating new ways of producing care

Acolhimento coletivo: um desafio instituinte de novas formas de produzir o cuidado

Acogida colectiva: un desafio instituente de nuevas formas de producir el cuidado

João Batista Cavalcante FilhoI,i; Elisângela Maria da Silva VasconcelosII; Ricardo Burg CeccimIII; Luciano Bezerra GomesIV

ICoordination of the Núcleo de Promoção da Saúde (Health Promotion Nucleus), Health Department of the State of Sergipe. Rua Francisco Rabelo Leite Neto, 670, apto. 202. Atalaia, Aracaju, SE, Brazil. 49.037-240 <joaoaracaju27@hotmail.com>

IIMunicipal Health Department of Recife

IIITeaching and Curriculum Department, School of Education, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul

IVHealth Promotion Department, Universidade Federal da Paraíba

Translation from Interface - Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, Botucatu, v.13, n.31, p. 315-328, Dez. 2009.

ABSTRACT

Within the challenge of implementing a form of welcome in which the team of healthcare workers would be made comprehensive, and would be thus in relation to users, a team of professionals from the family health program has proposed collective welcoming. This is a meeting space between workers and users that is focused on their health needs. Within this creative space, active work becomes stronger in relation to normative acts and, through communicative acts, transforms tension into understandings. There is a search for a metastable balance in which work is reconstituted in the light of each new challenge, thereby building relationships of greater solidity and providing learning for new ways of producing care.

Keywords: User embracement. Interdisciplinary healthcare team. Brazilian national health system. Primary healthcare.

RESUMO

No desafio de implementar uma forma de acolhimento que integralizasse a equipe de trabalhadores de saúde e estes com os usuários, uma equipe de profissionais do programa de saúde da família propõe o acolhimento coletivo, um espaço de encontro entre os trabalhadores e usuários, tendo por objeto as necessidades de saúde destes. Neste espaço criador o trabalho vivo ganha força na sua relação com os atos normativos, e por meio de atos comunicacionais transforma tensionamentos em entendimentos. Há a busca de um equilíbrio metaestável onde o trabalho se reconfigura diante de cada novo desafio, construindo relações mais solidárias e proporcionando aprendizado de novas formas de produção de cuidado.

Palavras-chave: Acolhimento. Equipe interdisciplinar de saúde. Sistema Único de Saúde. Atenção primária à saúde

RESUMEN

Ante el desafio de implementar una forma de acogida que integre el equipo de trabajadores de salud y estos con los usuarios, un equipo de profesionales del programa de salud de la familia propone la acogida colectiva; un espacio de encuentro entre trabajadores y usuarios, teniendo por objeto las necesidades de los usuarios. En este espacio creativo el trabajo vivo gana fuerza en su relación con los actos normativos. Por medio de actos comunicantes transforma tensiones en entendimientos. Hay la busca de un equilibrio meta-estable donde el trabajo se re-configura delante de cada nuevo desafío, construyendo relaciones más solidarias y proporcionando aprendizaje de nuevas formas de producción de cuidado.

Palabras clave: Acogida. Equipo interdisciplinario de Salud. Sistema Único de Salud. Atención primaria a la salud

INTRODUCTION

The Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS - National Health System) was instituted in Brazil by the 1988 Federal Constitution after a historical process of organized struggles around the movement of sanitary reform, synthesized by the argument that "Health is a right of all and a duty of the State". Since then, the SUS has been constructed in an attempt to implement principles such as: universality of access, healthcare equity and integrality, decentralization of sectoral management, regionalization and hierarchization of the services network, and popular participation with the role of social control.

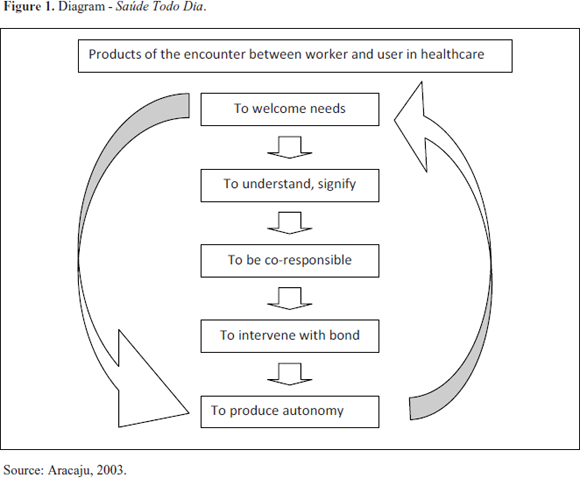

The proposition of Programa de Saúde da Família (PSF - Family Health Program) as a strategy to consolidate the SUS has happened from 1993 onwards and has been elected as a priority to reorganize the healthcare model, in the sense of reversing assistance models centered on the production of procedures destined to the cure of diseases, which have the hospital as their privileged place, towards models centered on care provided for individuals, considering their socioeconomic and cultural context and having, as their privileged place of action, the territory in which they are. The management strategy of the health sector that is being implemented in the municipality of Aracaju (Northeastern Brazil) was called Saúde Todo Dia (Health Everyday) and has been under construction since 2001. In its theoretical guiding model, Saúde Todo Dia has, as the object of its policies, the health needs of individuals and collectivities, and it considers health work as an encounter between users and workers in which the worker recognizes the users' needs, such as the right to health. The nature of the encounter between users who have health needs and workers who recognize these needs is the production of a process in which there is the welcoming of the other, the understanding and signification of his singularities and offer of health knowledge, enabling the professional to promote continuing interventions (bond) and to be accountable for the result of these interventions. The technical-assistance design of Saúde Todo Dia can be represented by the diagram of Figure 1.

In the project Saúde Todo Dia, we find that the implementation of welcoming was the first intervention on the working process. This intervention was fundamentally directed at the primary care network. The proposal of welcoming documented in the project was of amplifying the population's access by means of the substitution of the criterion "line" for that of "need duly qualified by health professionals". According to the project, based on welcoming, users should have access to a set of actions that are more adequate to their health needs.

Since its implementation, many formats of welcoming have been experienced by the health professionals of the municipality of Aracaju. A healthcare team faced the challenge of implementing a form of welcoming in which all its members contributed with their views, aiming to welcome the health needs of the enrolled population and making therapeutic projects emerge without disciplinary or meritocratic frontiers, working in a between-disciplinary perspective (Ceccim, 2006).

This essay configures a case study with a qualitative analysis of the practice of the healthcare team facing this challenge in the midst of PSF, choosing the collective welcoming as the format of this working process. We - the doctor and nurse of this team - used participant observation and conducted focal groups with the team, users and medicine students linked with the team in their education process.

We believe that the focal group is the means to make points of view and emotional processes emerge, allowing the apprehension of meanings that are difficult to be captured by other means. In the interaction, perceptions and meanings are constructed within the group, which would not happen in individual interviews (Gatti, 2005).

The participants, informed about the research methods and objectives and about the guarantee of the voluntary nature of their participation, signed a consent document, allowing the utilization of the information provided that anonymity was ensured. For this study, we conducted three focal groups: one with users (G1), another one with students (G2), and the third with professionals of the healthcare team (G3). Approximately three hours and twenty minutes of dialog were transcribed. The names, when cited, were purposefully replaced by fictitious names. To G1, we randomly chose two users present in the collective welcoming and invited on each day of the week, totaling ten invited users, of whom six attended the group session. G2 was composed of the four Medicine students who participated in the collective welcoming in their education process, as part of the Public Health internship of Universidade Federal de Sergipe. In G3, the following team members participated: doctor, nurse, nursing assistant and four community health agents.

In the groups that were conducted, we assumed the role of group mediators and participants. Far from being impartial, we believe that, being part of that group of healthcare workers, we should participate in their reflection and construction of syntheses.

By means of the bibliographic review, we attempted to discuss the concepts of welcoming and the tools to evaluate its caregiving nature, with the aim of amplifying/qualifying the capacity of reflection on our reality and of structuring the experience as a militant action, so as to contribute to the defense of life and the real implementation of the SUS.

What is welcoming?

To analyze collective welcoming, it is necessary to investigate what has already been produced intellectually about welcoming. With a large and recent theoretical contribution and due to the varied activities performed at healthcare units, the word welcoming ends up carrying a polysemy, acquiring countless meanings, "souls", senses. We do not aim to find a definition for welcoming, as the reflections on the theme, when compatible, become complementary and, viewed together, are essential for structuring our praxis.

In a class given in the specialization course in Public Health of the Centro de Educação Permanente em Saúde de Aracaju and Universidade Federal de Sergipe in 2005, Emerson Merhy approached welcoming as a "non-place", the encounter between healthcare worker and user, in which the latter tensions the entrance into the healthcare network, trying to show that he deserves to receive care. There is an appeal by means of communicative acts so that a certain need is considered (Merhy, 2005).

A health professional suffers the influence of many normative acts, but the co-existence between these normative acts and the communicative ones is not resolved in the level of assistance rules or protocols. It requires analyzing certain territories, like that of power and that of communicative relations. One of the solutions would be bureaucratizing this relationship1 consecrating the rules, which can open or close the public spaces to users, in the same way that it can allow or hinder the performance of communicative acts and, thus, deny or offer a form of care.

Teixeira (2005), in a discussion about the question of integrality, views welcoming as a network of conversations. The author states that the different conceptions of integrality depend on what the different technical-political projects intend to integrate, in the sense of combine into a whole. This question would focus on the "worker-user relationship that takes place in the services, to which the strongest desires of integration are directed"2 (Teixeira, 2005, p.91). It would be necessary to integrate the voice of the other in this process, overcome the monopoly of the diagnosis of the needs of the other by professionals or certain health professions.

In addition, Teixeira states that the substance of health work is conversation, in which people work with an object that is necessarily relational, shared by all the present players. Thus, the author understands the care network as a network of conversations that permeates all the moments of the workers-users encounter and the flows of care. Teixeira argues that welcoming-dialog or dialoged welcoming should be understood as a central attitude in the living work, in act, and that it should be guided by moral and cognitive positions that consider alterity, the real insufficiency of the different players, and the need of integration of the present knowledge.

To Merhy et al. (2004), the encounter between worker and user starts a relational process in which the living work, in act, operates. The encounter triggers a process of technological intervention involved in the maintenance/recovery/alteration of a certain way of conducting life. Welcoming also allows arguing about the process of production of the user-service relation in the perspective of accessibility. It would have the power of: building bonds and accountability, provoking noise in the moments in which the service welcomes its user and evidencing the dynamics and criteria of accessibility to which users are submitted; it can produce new dynamics, which institute new lines of possibilities to produce care. It is a chance of transforming the service into a user-centered form, reducing the centrality of medical consultations and better using the potentials of other professionals.

Silva Júnior and Mascarenhas (2006) argue that welcoming has three dimensions: of posture, of technique and of the principles of services reorganization. In welcoming, the issues of subjectivity and individuality, the search for meanings and for what has not been said have weight. Welcoming requires the mobilization of knowledge to provide answers, leading to a posture of enrichment of the therapeutic arsenal, aiming to enhance the interventions. Teamwork is included in this arsenal, but it searches for its articulation, not its alienation. Welcoming opens a dialogic space to extirpate alienation, respects the subject, negotiates needs and rearticulates the services.

Based on our reading and experience, we highlight welcoming as a device to amplify accessibility to the health services; a device that structures the working process centered on health needs; with potential to institute new forms of producing care; as a space of integration of the user's voice in the construction of therapeutic projects; and as integration of professionals and their knowledge with the aim of providing care for the population they assist, in a between-disciplinary perspective, like the one proposed by Ceccim (2006).

Care production and teamwork

Far from trying to exhaust the discussion on health work, we depart from an analysis that extrapolates the operative dimension, as an activity, but, above all, "a praxis that exposes the man/world relation in a process of mutual production" (Merhy, 1997, p.81).

When we problematize health work as health production, we might ask what the health worker produces. Generically, we could answer that he produces health acts, but the question to be answered is: what is his object of action? The way in which the health worker constructs his object of action becomes central to his production of health acts. We argue, following Merhy (2005), that one of the health professionals' necessary competencies is being attentive to the "negotiation" of needs. Negotiation is understood as a dialog or "balance" of the network of conversations between the technical references and lived experiences that define or distinguish the health needs.

Welcoming a need as a health need will depend on the actors on stage, on the construction of the object of action, on the form in which this process takes place and on the possibilities of negotiation. There is no simple answer to this complex situation. This process cannot be managed simply by appealing to the professionals' good conscience, because we would have to tackle the setback of establishing what this good conscience would be and, also, we would have to find a form of selecting the good professionals. What should be attempted and can be guaranteed is the construction of public spaces for the negotiation of needs, ensuring the dispute of the meanings of the professionals' object of action.

Every encounter brings tension to the public space of negotiation; there is an appeal by means of communicative acts so that a certain need is taken into account. If the health professional is tied to the bureaucratized action, is tied to the normative act, he will not consider as his competence the recognition of this space for public dialog, which opens new meanings to his relation with the user. If the worker does not signify this competence of recognizing the movement of social construction of the health needs, he will not be able to welcome them, independently of normative acts and models.

If the health worker produces health acts and his object of action is care, then, care production assumes the character of affirmation of life defense, to the detriment of the production of procedures, which is so necessary to the capital reproduction that is present in the medical-industrial complex, but which is different from accepting life's complexity and frailty.

Many studies (Pinheiro, 2006; Merhy, 1997) point to the crisis of the model that supports the medical-industrial complex, the biomedical model. Users' submission to the professional's will, the medicalizing character, the valuation of biological aspects, impersonal care and the abuse of complementary tests are some of the factors that would point to the foundation of this crisis. "It seems that the explanatory model to the health problems presented by the population does not have similarities to the models used to elucidate diseases - at the same time in which this constitutes the central element of the rationality of medical practice, which is hegemonically exercised in the health services" (Pinheiro, 2006, p.78). Â

The medical-hegemonic work, as it also determines the production of procedures, assumes the center of capital reproduction to the detriment of the defense of life. Ideologically, the consumption of procedures starts to be faced, even by the population itself, as capable of producing care, a power that exists only in the field of ideation. There is a "reductionism of clinical practice, simplifying the idea of healthcare production" (Franco, Merhy, 2005, p.185). The working processes focus on the instrumental logic, to the detriment of more relational approaches.

The complex reality ends up tensioning through lines of flight of the instrumental logic. Merhy (2002) says that if the working process is always open to the presence of the living work in act, it is because it can always be crossed by the distinct logics that the living work can contain. From the moment in which a public space is opened to the negotiation of health needs, one of the logics that may try to tension what is instituted is the user's logic. The communicative acts can fill the space of the encounter between workers and users, and they can make a dialogued therapeutic project emerge from this encounter, a project that uses the knowledge of both players and the multiple technologies that are available in the space, employing creativity and, only thus, producing care.

Franco and Merhy (2005) argue that the challenge to those who work with health is that of constructing health production processes that are able to be consolidated with new references to users, assuring them that a model centered on soft technologies, which are more relational, can provide care in the way they imagine or desire it.

Another relevant datum is that no professional has all the necessary tools to provide care. Teamwork is necessary. To Ceccim (2006, p. 262), "every health professional, due to their condition of therapists, should have, with appropriateness and accuracy, clinical intervention resources and instruments", but this can only be exercised in the perspective of sharing and matrix-based strategies. Merhy (2002) believes that it is vital to understand that the health workers present intervention potentials in the care production processes. These potentials are marked by the specific nuclei of competence of each profession or professional occupation, "associated with the caregiver dimension that any health professional holds, no matter if he is a doctor, a nurse or a (watchman) of the door of a health establishment" (p. 123). The loss of this caregiving dimension can be pointed as another cause of the current serious crisis of the medical-hegemonic model.

We believe that a movement of change is under way and that we are participating in it. This movement is a response to the crisis of the biomedical model. The following are new factors of the clinic in current times: the need to integrate the other in his individual therapeutic project, of knowing the meaning of his sickening process, of integrating his actions and his references of explanation about what he feels and the processes he undergoes, of acting with him in his search for autonomy and happiness.

The integration of the other also crosses integration within the healthcare teams. Professionals alienated from the care production process, in a doctor-centered and procedure-centered model, will hardly recognize themselves as performers of health acts, and will hardly recognize their caregiver potential. Instead of visualizing their role, they perform an act that is simply reproductive, disconnected from the production of the use value of the health product (in this case, health acts), with damage to their transformation through work, to their satisfaction as authors of the working process, as fulfillers of a work (Campos, 2000).

Ceccim (2006) defends between-disciplinarity so that team relations are permanently reconfigured in order to cope with the complex real world of health needs, which struggle to be recognized and cared for. The author proposes between-disciplinarity as a way of understanding multiprofessional and interdisciplinary work, "a place of sensibility and metastable balance3, in which therapeutic practice would emerge as a mestizo clinic or nomad clinic; in which all potentials would continue being updated and balance would be related only to the permanent transformation of oneself, of the surroundings, of work" (Ceccim, 2006, p.265).

This permanent transformation breaks the logics of closed and programmatic agendas. It challenges what is instituted, the resistances. Communicative acts creatively complexify the focus on the reported needs, which sometimes contain much more silences and requests of care (Cecílio, 2006). It is not enough to form teams with professionals from several areas. It is necessary that the knowledge and technologies circulate in the benefit of care.

Placing the caregiver potential, the knowledge and actions of each professional that composes the healthcare team in a space that welcomes health needs, with the objective of integrating this work, is one of the challenges of collective welcoming. Disalienating the role of each one in care production, making between-disciplinary therapeutic projects emerge, circulating looks and desires, is a way of making our work become a daily creative work. In this integration movement, which also integrates users, we are getting close to the space where collective welcoming takes place.

Collective welcoming

The drawing of Figure 2 is a graphical representation that displays the paths to the production of caregiving therapeutic projects using collective welcoming. This would be the moment of the encounter, a creative space.

Users arrive at the Healthcare Unit. Even though the team explains everyday that it is not necessary to arrive right after the opening of the Unit, at seven o'clock in the morning, some of them find it difficult to disregard the history of access to the services in order of arrival. We sit in a circle in the unit's meeting room, all the team workers (doctor, nurse, nursing assistant and community health agents) and users. Eyes and expectations intersect.

We explain the functioning of the Unidade Básica de Saúde (UBS - Primary Care Unit) and talk a little about some problem considered a health problem by the team or brought by the users at that moment. There is no agenda. We discuss a range of subjects, from the increase in violence in the neighborhood to hypertension control, from diabetes to the problem of open pits that cause so much trouble to some inhabitants. The word is given to anybody who wants to use it.

A public space is opened to negotiation/conversation about health needs. We try, in every possible way, to transform tensions into understanding. In this intercessional space, there is the need to integrate the other, the team and the professionals. In this communication web, the communicative acts take place, moving needs that had not been seen before to the category of health needs, which allow seeing beyond the demand that is brought.

After a debate that lasts between thirty and forty-five minutes, depending on the number and participation of users, the approach becomes individual, right there at that room. Each professional welcomes one person at a time. The entire team handles these cases and learn with them everyday, because with the open conversations, one professional solves doubts and proposes answers to another person (professional or user). Different problems are discussed, different interventions and articulations of the work of each professional are proposed. Many times, the answer or the proposed path for the user to conduct his life in not contained in protocols. We find there an instituting challenge, seeing and acting beyond the norms, instituting new ways of providing care.

Serious cases receive immediate attention in the unit's observation room (sometimes, even before the dialogue starts), where there are resources for emergency assistance.Â

Acute cases are those that will be analyzed in a medical or nursing consultation in that same shift, because without receiving assistance in 24 hours they may become more serious. Instructions are given to varied doubts and can represent a calm rest of the day or an immediate intervention. Space is guaranteed for those who want to talk outside the meeting room, in one of the unit's rooms.

The team's agendas, with their structured offers, can be freely accessed by any of its professionals. Each user has the beginning of his singular therapeutic project in the welcoming, and he can be included in any of the offers: consultations with higher education professionals, home visits, programmatic actions. During approximately one hour, with all the professionals involved in welcoming, the users' projects have already begun or are under way. Then, the doctor and the nurse start to assist acute cases and, after them, the scheduled cases.

According to Tesser, Poli Neto and Campos (2007),

[â¦] the more flexible and versatile the professionals, the more diversified and less ritualized their actions, the more mixed people are, working together, the more open and accessible the service is to all types of demands, the more likely the team is to be immersed in the socio-cultural world of its catchment area, to exchange personal and professional knowledge, to perform welcoming in a better way and guarantee the access.

Doctor, nurse and assistant, together with another healthcare team that shares the same unit, ensure the provision of individual welcoming during the whole day. However, it is known that, culturally, the majority of the population of the catchment area seeks for assistance in the early hours of the morning. There is an articulation of the professionals' agenda with the aim of guaranteeing, after the end of collective welcoming: the programmed consultations, actions relating to each nucleus, team meetings, home visits, and health education, distributed throughout the teams' working week. There is also some flexibility in this configuration to ensure joint actions among the professional nuclei.

"I'm here referring to the first qualification course we took about welcoming. At that moment, in the Center for Permanent Health Education, welcoming was a disruption, a disruption of that healthcare user's arrival that used to be that line, arriving at dawn⦠this new system allows that people go out of the healthcare unit after having been heard [â¦]. I participated in the individual and in the collective welcoming [â¦]. In one level of welcoming the patient's demand, today the professionals have already mastered what welcoming means. But another level would be embracing this family to do this welcoming. I consider individual welcoming more efficient in the sense of welcoming the patient's demand. And I consider collective welcoming, this one in which I'm participating for the first time, more efficient in welcoming as a whole [â¦]. I see this in a good way, it's efficient, because collective welcoming eliminates what is unnecessary in welcoming, it is more efficient in providing solutions." (Nursing assistant)Â

Welcoming aims to ensure universality with qualified hearing of everyone that arrives at the healthcare unit. Let necessity define the configuration of offers, and not the contrary. Let responsibility towards the user guide the working process, and not other interests, like the corporative ones. Guaranteeing individual welcoming during and after the performance of collective welcoming complies with this precept, as not all problems should be shared, independently of the reasons. Besides this role, individual welcoming within the team's working process has the perspective of creating a bond with the users that arrive at the unit at other times, even though the unit is open only during business hours, even though this hinders the access of the working class.

With the difficulty in access caused by the limitation of file cards, the users, attempting to guarantee assistance, had to arrive at the line very early in the morning, running the risk of not receiving assistance. Being able to be heard more quickly, due to the fact that the entire team welcomes, and not needing to arrive at the unit at dawn, are extremely valued:

"We used to go there, filled in the card and stayed there many hours. Sometimes, we had to arrive there at 5 in the morning. About three months ago, this stuff of being welcomed at the room [collective welcoming] started. I have nothing against it, we arrive there, you ask what the matter is, due to the problem the person receives assistance right away, doesn't wait until 12 o'clock [noon]". (User)

"I think that it increases the [user's] self-esteem. There is that image that, because I'm poor I have to arrive at 5 in the morning and receive assistance at 8⦠Now I arrive at 8, receive assistance and, depending on my case, at 9 I'm already at home. This increases the self-esteem, gives more quality of life and there's still time to cook lunch!" (Medicine student)

The welcoming is fast because the whole team performs the qualified hearing. As everybody will be heard according to their needs, the flow of users improves. The overload of the entrance door early in the morning, which used to be the responsibility of the nurse alone, now is shared with the other team members:

"Another factor in this kind of welcoming is that we're also sharing some of this load. It's not just the nurse who's assisting alone a line of forty people. When welcoming is performed individually, when the twentieth person comes, of course the nurse is saturated and does not assist the 21st in the way she assisted the first one. When we see many people in the welcoming room, we [healthcare team] look at each other and we know we're going to share that". (Nurse)

"You arrive at the welcoming line and there's a nurse who's going to assist you. That nurse is the one who will decide if you'll go to what you want to consume. What does this population want to consume? Culturally, the medical consultation, because our model has always been centered on the doctor. In that space we have the opportunity to say: now the welcoming is of the team. This takes it away from the doctor. I [the user] seek for welcoming. This healthcare team, together with me, is the one that is going to decide what will solve the problem [â¦]. I see teamwork, it gets away from that stuff of being assisted only by the nurse. Because what can also happen is the nurse being seen as the wicked one in the story, I didn't go to the doctor because the nurse didn't refer me to the doctor". (Doctor)

The collective welcoming's attempt to transform the model, remove the centrality from medical consultations and amplify the potentialities of the professionals who form the team is well explored by Merhy et al. (2004), who emphasize the radical change that welcoming causes in the working process of a Healthcare Unit. The Welcoming Team becomes the center of the activities in user assistance and "the professionals who are not doctors start to use their entire technological arsenal, the knowledge for assistance, in hearing and solving the health problems that are brought by the population that uses the Unit's health services" (Merhy et al., 2004, p.45).

The doctor's social construction as the holder of the knowledge that will be transmitted for the user's cure is one of the barriers to be overcome in order to replace the consumption of consultations by between-disciplinary caregiving therapeutic projects. The social and economic status and the biologicism of health education make the dialog become unequal and do not favor it. The view of health as a commodity, and not as a right, ideologically strengthens the valuation of specialization in health (more expensive product) and of the performance of tests which, many times, are unnecessary (more expensive procedures), not to mention medicalization. The dialog is not considered therapeutic and is viewed as not being efficient in problem-solving. This permeates the entire health education, and is very strong in doctor's education:

"If consultations could be scheduled to everybody, collective welcoming would not be necessary". (Medicine student)

"I think that in some moments it [collective welcoming] is therapeutic¸ sometimes it's only a palliative. If all patients are referred to consultations, there will be no time". (Medicine student)

"I don't like Dr. Silvia because I asked for some tests and she asked me if I thought they were really necessary. Well, my son only likes breasts [maternal milk]. He doesn't even like danone [yogurt]. The child doesn't eat anything. She requested the tests reluctantly. What if he had some serious disease?"(User)

Bringing to light this and other conceptions facilitates dialog. Listening to a patient, informing him about self-limited diseases, and scheduling his return to see their resolution may have a therapeutic and bonding character that is greater than our current means of investigation are able to capture. The inclusion of the other, his voice, the sensation of involvement in the process, the deterritorialization of the health professionals to the circle, circulates, besides knowledge, power, with reflexes on autonomy construction. Collective welcoming becomes an escape from the ideologically constructed image of the health professional, mainly those with a university degree, as the holder of the knowledge to be transmitted instead of shared:

"Before, the doctors were seen only at the moment of the consultation. He was a pop star [laughs]. He entered through the unit's back door, he went out through the back door, he was seen only in the moment of the consultation. Just this [being present in the welcoming circle] already is a great difference for the population". (Nursing assistant)

"[The healthcare workers] treat us well, ask what we're feeling, talk to us politely, if we are in pain we are assisted before long, it's much better. Before it used to be so bad, we waited outside, and waitedâ¦". (User)

The space of the dialog, its comprehension as a place of exchanges and understandings, sometimes is not perceived as such. The scarcity of public spaces of negotiation, the distance between technical knowledge and popular knowledge, the class differences, the valuation of one culture to the detriment of others, social exclusion, are aspects that, sometimes, are not overcome and jeopardize dialog.

The answer given by the team is to guarantee the space of reterritorialization - the professional, the user, the room - verbally, in the collective welcoming. Besides the fact that the team maintains collective welcoming open during the unit's working hours.

"I worry about people's cultural level. Sometimes, they want this differential assistance [individual assistance, in the room] and don't express it in the circle". (Medicine student)

"Many people feel at ease, but many people feel cornered, scared of making mistakes while talking. You know, people from a lower class [â¦] but in my point of view we have to speak. So many people have degrees and make mistakes [â¦] Some don't like talking because they feel shy, scared. But we have to say how we feel". (User)

"If it's necessary, he [the user] shouts, he speaks. Only a minority keeps silent. If he's not enjoying it, he opens his mouth and says so. Here, people have freedom to say what they think, many times, even if it hurts someone else". (Community Health Agent)

"But when we say that anyone who wants to speak in private just has to say so, this is also intimidating. People may think I have some serious stuff [serious disease]. He prefers to schedule a consultation and wait". (Nursing assistant)

The population gathered can express needs of the collectivity, and new voices are integrated into care production. The new therapeutic projects make us learn with the new practices of facing challenges. In addition to more needs, views, prejudices and conceptions come to light.

"Sometimes the person comes here only to schedule a consultation and we ourselves can take the nurse's appointment book and do so. If the person wants to talk to the doctor, we say: wait just a little. And as everybody is together [â¦] formerly, the doctor and the nurse didn't stay together with the user, everybody talking [â¦]. Even he has something that involves more secrecy, he doesn't tell and he tells it individually and he'll be assisted according to his needs. As soon as possible. My area [catchment area] has approved it and I hope it doesn't change in the near future". (Community Health Agent)

"And we learn with each other. Sometimes, a patient has a problem that he doesn't want to tell us and we say: say more or less how it is, wait a minute that I'll talk to the doctor". (Community Health Agent)

"He's already acting like a doctor [laughs]" (Community Health Agent, after the speech above)

We already know more or less which case the doctor assists, which case the nurse assists. When they come to me I already pass them to him. We develop ourselves a lot". (Community Health Agent)

"They [the users] give their opinion about what is happening, if it's good or bad to them in relation to the unit and the community. There they have a greater opportunity, even those who are ashamed of talking". (Medicine student)

"In collective welcoming, a problem of the population becomes more visible. If you see many pregnant adolescents in the collective welcoming, you are going to approach sexual education. So, this welcoming is not the responsibility only of the health agent, it goes to the whole team." (Medicine student)

Health needs determining the team's action. Movement and life to be defended in the construction of caregiving, integrative therapeutic projects, building autonomy. The search for an inclusive Health System and for a working process that brings also the professional fulfillment of the members of the healthcare team.

Provisional synthesis

Collective welcoming as a proposal for the organization of the healthcare team's working process is innovative because it is a space for the integration of the other, users and workers, and also of knowledge. The horizontal dialog with users and the relevance given to their opinions and desires provide the unit with a profile of therapeutic space and integral healthcare, enabling, also, that the professional gets in close contact with the way of living and feeling the needs that are brought to the space by the population.

The greatest challenge of placing oneself in a public space of negotiation is the sensation of lost security that occurs in the search for metastable balance. The search for this balance, this instituting challenge, brings with it new forms of producing and being happy at work.

Even considering the bias of gratitude in the focal group of users, where there is almost unanimity concerning the conduction of collective welcoming, it is possible to feel that the tensions have been reduced in the unit's daily routine, tensions which used to be so frequent before, certainly due to lack of conversations.

The collective hearing conducted in the studied format of welcoming brings one more place of identification of health needs. We argue that it is the health need that should define/institute the offers of a service. Instituting not always means substituting. There are needs and negotiations that only emerge in the individual and more private approach that the collective welcoming can give. Collective and individual welcoming become, then, complementary in the qualified hearing of health needs.

Collective welcoming requires units with good physical space, which is not always a reality of our health system. It also requires professionals who amplify the caregiving dimension of their actions and flexibilize these actions according to the health needs.

The hospital-centered and biologicist education in health has not been preparing professionals with the competence of creating public spaces for negotiation, of working in teams or recognizing, respecting and integrating the other. The defense of life and of the National Health System is one of the changes that these professionals' education must undergo.

Collective welcoming is not a screening. It goes beyond the classification of risks that determines the sequence of actions in favor of the recovery of health. It is not a waiting room. It is a space of encounters where knowledge circulates and it is not only transmitted from the wise to the ignorant. It is not a pre-consultation. It is the integration of workers and users for the construction of individual and collective therapeutic projects considering expectations, theoretical frameworks, desires, feelings and experiences.

Spaces like this are not so common in our healthcare units. There still is much to deconstruct/construct in our ideas so that we are allowed to break the obstacles to dialog and so that this search for balance produces more solidarity and more humane relationships. Sharing this with users and workers has an immeasurable value. Reflecting on our practice brings more clarity and satisfaction with the path we take. Systematizing and sharing this experience by means of this work brings with it the hope of promoting understanding and more reflections on the daily actions of the militant workers, our companions spread across Brazil.

COLLABORATORS

João Batista Cavalcante Filho and Elisângela Maria da Silva Vasconcelos were responsible for all the stages of the production of the paper. Ricardo Burg Ceccim and Luciano Bezerra Gomes were responsible for discussing and writing the paper.

REFERENCES

ARACAJU, Secretaria Municipal de Saúde. Projeto Saúde Todo Dia. Aracaju, SE, 2003.

Aula da especialização em saúde coletiva com Dr. Emerson Merhy em 12/08/05. Aracaju, SE. Videoteca do Centro de Educação Permanente da Saúde, Agosto 2005.

BOUFLEUER, J.P. Pedagogia da ação comunicativa: uma leitura de Habermas. 3ºed. Ijuí: Unijuí, 2001.

CAMPOS, G.W.S. Um método para análise e co-gestão de coletivos. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2000.

CECCIM, R.B. Equipe de saúde: perspectiva entre-disciplinar na produção dos atos terapêuticos. In: PINHEIRO, R., MATTOS, R.A Cuidado: as fronteiras da integralidade. 3º ed .Rio de Janeiro: IMS / Uerj / ABRASCO, 2006. p. 259 - 278.

CECÍLIO, LCO. As necessidades de saúde como conceito estruturante na luta pela integralidade e equidade na atenção em saúde. In: PINHEIRO, R., MATTOS, R.A. Os sentidos da integralidade na atenção e no cuidado à saúde. 4 ed. Rio de Janeiro: CEPESC/Uerj/IMS/ABRASCO, 2001. p. 113-126.

CORDEIRO, H. Descentralização, universalidade e eqüidade nas reformas da saúde. Ciência & saúde coletiva, 2001, v.6, n.2, p. 319-328.

FRANCO, T.B. et al. Acolher Chapecó: uma experiência de mudança no modelo assistencial com base no processo de trabalho. São Paulo: Hucitec,2004.

GATTI, B.A. Grupo Focal na pesquisa em ciências sociais e humanas. Brasília: Líber Livro, 2005.

MALTA et al. Acolhimento: um relato da experiência de Belo Horizonte. In: REIS, A.T. et al (org.). Sistema Único de Saúde em Belo Horizonte: reescrevendo o público. São Paulo: Xamã, 1998. p. 121-142.

MERHY, E. et al. O trabalho em saúde: olhando e experenciando o SUS no cotidiano. 2 ed. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2004.

MERHY, E e ONOCKO, R (Org.). Agir em Saúde: um desafio para o público. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1997.

MERHY, E. Saúde:Â cartografia do trabalho vivo. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2002.

MINAYO, M C S. O desafio do conhecimento: pesquisa qualitativa em saúde. São Paulo:

Hucitec; Rio de Janeiro: Abrasco, 1999

PINHEIRO, R. e MATOS, R A. (Org.). Construção Social da demanda: direito à saúde, trabalho em equipe, participação e espaços públicos.Rio de Janeiro: Cepesc/Uerj/Abrasco, 2005.

SILVA Jr, A.G. e MASCARENHAS, M.T.M. Avaliação da atenção básica em saúde sob a ótica da integralidade: aspectos conceituais e metodológicos. In: PINHEIRO, R., MATTOS, R.A. Cuidado: as fronteiras da integralidade. 3º ed.Rio de Janeiro: IMS / Uerj /Abrasco, 2006. p. 241-257.

TEIXEIRA, R.R. O acolhimento num serviço de saúde entendido como uma rede de conversações In: PINHEIRO, R., MATTOS, R. Construção da Integralidade: cotidiano, saberes e praticas em saúde. 3º ed.Rio de Janeiro: IMS / UERJ / ABRASCO.2005. p. 89-111.

i Addrees: Rua Francisco Rabelo Leite Neto, 670, apto. 202. Atalaia, Aracaju, SE, Brazil. 49.037-240

1 Merhy (2005), accessing Habermas' theory of communicative action, states that this would be the capture of a space that should defend life by the instrumental logic. The communicative act that operates in the relationship in a dialogic posture would be the opportunity of tensioning instrumental reason, in which the rules that are external to the subject dominate, the normative acts.

2 All the quotations were translated into English for the purposes of this paper.

3 We understand metastable balance as ongoing balance, an instituted that calmly opens its door to the instituting that emanates from the relations with the other, and with the complex reality that insists in escaping from being captured. And, for this reason, it moves, modifies, embraces, integrates, welcomes, cares for. The commitment is to the defense of life¸ man's happiness and emancipation.