Meu SciELO

Innovar : Revista de Ciencias Administrativas y Sociales

versão impressa ISSN 0121-5051

Innovar v.1 n.se Bogotá 2008

Recognition and recall of product placements in films and broadcast programmes

Reconocimiento y recordación de los productos exhibidos en películas y en programas emitidos por televisión

Reconnaissance et évocation de produits placés dans des films et des programmes de télévision

Reconhecimento e recordação dos produtos exibidos em filmes e em programas emitidos por televisão

D. L. R. van der WaldtI; L. D. Du Preez; S. Williams

IDr De la Rey van der Waldt is Subject Head: Communication Management in the Department of Marketing and Communication Management, Faculty of Economic and Management Science, University of Pretoria, Republic of South Africa. This article is based on a survey conducted by L. D. Du Preez and S. Williams as part of their honours degree project. Email: Delarey.vanderwaldt@up.ac.za

Replicated from Innovar, Gogotá, vol.18 n.31, p.19-28, Jan./June 2008.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to investigate product placements in films and broadcast programmes regarding recognition and recall of product names. The sample consisted of undergraduate male and female students aged 18 to 24 attending a tertiary level institution in Pretoria, South Africa.

The findings showed that even though there was no perfectly positive relationship between the prominence and recognition of products placed in films, someone watching a film was more likely to recognise a product if it were to be shown audio-visually. It can therefore be concluded that if a product is placed more prominently in a film, the recognition thereof will be higher.

This study can be a benchmark as it is one of the first studies conducted in South Africa regarding the perception of product placements in film.

Key words: Product placements, recognition, recall, film, television, advertising, new media, consumers.

RESUMEN

El propósito de este artículo es investigar la exhibición de productos (product placements) en películas y en programas emitidos por televisión, para determinar el grado de reconocimiento y recordación de los nombres de estos productos. La muestra estuvo comprendida por un grupo de estudiantes de pregrado de una institución universitaria de Pretoria, Sudáfrica. Las edades del grupo oscilaban entre 18 y 24 años, con individuos de ambos sexos.

Los hallazgos mostraron que a pesar de no existir una relación perfectamente proporcional entre la prominencia y el reconocimiento de productos mostrados en una película, un espectador es más dado a reconocer un producto si se muestra en una combinación de estímulos auditivos y visuales. Por tanto, se puede concluir que si un producto se exhibe de manera prominente, su reconocimiento posterior será más alto.

Este estudio puede tomarse como punto de referencia sobre la comprensión de los "product placements", por constituirse en uno de los primeros estudios realizados en Sudáfrica en este campo.

Palabras clave: Exhibición de productos, reconocimiento, recordación, películas, televisión, propaganda, nuevas tecnologías de comunicación, consumidores.

RÉSUMÉ

L'objectif de cet article est d'étudier le placement de produits (product placements) dans les films et les émissions télévisées, afin de déterminer le degré de reconnaissance et d'évocation des noms de ces produits. L'échantillon, un groupe d'étudiants et d'étudiantes universitaires de Pretoria, Afrique du Sud, correspondait à une tranche d'âge de 18 à 24 ans.

Selon les résultats obtenus, même s'il n'y a pas de rapport totalement proportionnel entre la proéminence et la reconnaissance de produits placés dans un film, le spectateur est plus enclin à reconnaître un produit lorsque celui-ci apparaît accompagné de stimulus auditifs et visuels. Ainsi, il est possible de conclure que lorsqu'un produit est placé de façon proéminente dans un film, plus tard il sera reconnu davantage.

S'agissant de l'une des premières études réalisées en Afrique du Sud dans ce domaine, elle pourra servir comme point de référence pour comprendre les « product placements » dans les films.

Mots clé: Placement de produits, reconnaissance, évocation, films, télévision, publicité, nouvelles technologies de communication, consommateurs.

RESUMO

O propósito deste artigo é investigar a exibição de produtos (product placements) em filmes e em programas emitidos por televisão, para determinar o grau de reconhecimento e recordação dos nomes destes produtos. A amostra esteve conformada por um grupo de estudantes de graduação de uma instituição universitária de Pretoria, África do Sul. As idades do grupo oscilavam entre 18 e 24 anos, com indivíduos de ambos os sexos.

As descobertas mostraram que, apesar de não existir uma relação perfeitamente proporcional entre a proeminência e o reconhecimento de produtos mostrados em um filme, um espectador de filmes é mais propenso a reconhecer um produto se este é mostrado em uma combinação de estímulos auditivos e visuais. Portanto, pode-se concluir que se um produto é exibido de maneira proeminente em um filme, seu reconhecimento posterior será mais alto.

Este estudo pode ser tomado como um ponto de referência sobre a compreensão dos product placements nos filmes, por constituir-se em um dos primeiros estudos realizados na África do Sul neste campo.

Palavras-chave: Exibição de produtos, reconhecimento, recordação, filmes, televisão, propaganda, novas tecnologias de comunicação, consumidores.

1. Introduction

A study by Russell (2002: 307) indicates that prominence plays an important role in the recognition and recall of product placements in films because firms spent more than US$1.5 billion on product placements during 2005, followed by Brazil and Australia with a spent of $285 million and $104 million, respectively (ABC Arts, 2006: 1). The advancement of new technological devices as communication vehicles will cause traditional advertising to become less significant (Hornick, 2006: 1). The biggest advantage of product placements is the fact that the message has a wide reach and a long life with declining cost per exposure (Wiles & Danielova, 2006: 3).

Product placements in film, according to Balasubramanian (1994: 2), can be seen as "hidden but paid" messages that include product names, products, or the name of a firm aimed at film audiences via the unobtrusive entry of product identifiers through audio and/ or visual means for promotional purposes.

According to Dodd & Johnstone (2000: 142) and Mc- Kechnie & Zhou (2003: 350), the advent of digital television, the Internet, the growing numbers of commercial radio stations and increased household penetration of internationally broadcast cable and satellite channels, as well as video cassettes and DVD players, have significantly increased the choice of where to place product advertising in a medium. It has also highlighted the need for communicating more effectively with potential consumers. A typical film with international distribution can reach over one hundred million viewers as it moves from box office to video/ DVD to television (Vollmers & Mizerski, 1994: 98). In order to reach this vast number of consumers and to secure competitive advantage among them, advertisers should seek to exploit previously under-used channels of communication. One of these channels is product placement (Dodd & Johnstone, 2000: 142).

Product placements make a significant contribution to the story line of a film, adding realism and credibility, thus facilitating memory (Russell, 2002: 308). There are three ways in which products can be featured in a film, which are identified by Smith (1985: 85): the product itself, a logo is displayed or an advertisement is placed as a background prop.

DeLorme & Reid (1999: 2), Belch & Belch (2001: 459- 460), and Fill (2002: 724) put forward a number of advantages of product placements. The advantages of product placements include: Exposure to the product means that the levels of impact can be high because cinema audiences are very attentive to large-screen presentations. On average, the life span of the film is estimated at three years. When this is combined by the video and DVD rental market and television broadcasting of the feature film, it is extended for a much longer period. The frequency of placement in the feature film relates to the manner in which the product is presented or used in the film, and it could be repeatedly exposed during all the film. Product placements could also be a support for other media. Source association is another advantage of product placements. When film attendees see their favourite film star using the product, the impact of this exposure could be high. The cost for placing products in feature films may range from free samples to millions of ZA Rands. The cost per minute of this form of advertising can be very low in comparison to other media, due to the high volume of exposures it generates. Average recall of products that were placed in feature films showed approximately 38% the next day (Gupta & Lord, 1998, in Belch & Belch, 2001: 459). Bypassing regulations is another advantage of product placements in a feature film. Product placements allow for cigarettes and alcohol manufacturers to expose their products, circumventing these restrictions.

However, according to DeLorme & Reid (1999: 2),

the disadvantages of product placements are that marketers and advertisers have limited control over the product placement process. It includes the inability to guarantee the release date or the success of a particular film, the possibility of a product being edited from the film, the risk of negative or unclear product portrayal in the film setting, the difficulty in measuring effectiveness, and the lack of audience selectivity in the film medium.

From the disadvantages mentioned above, management can easily identify the obstacles that they may be faced with when working with product placements.

2. Research problem and objectives

Little published information exists in a South African context on product placements in films (EbscoHost, Emerald and Science Direct search engines [Accessed: January-February 2008]. Van der Waldt (2005: 13) states that attention should be given to recognition and recall as a focus of future research. It is therefore necessary that marketers determine which product should be placed, where, and in which film, with the intention to increase recognition and recall of these placements in the mind of film attendees. This study was undertaken to investigate the usage of products in films and the perception of males and females in this regard. The researchers aimed to answer the following research questions:

Do film attendees recognise products placed in films?

Do film attendees recall products placed in films?

3. Literature review

3.1 Recognition

According to Dodd & Johnstone (2000: 143), product recognition can be seen as a person's ability to identify a product name in a film. In order to a product to be effectively recognised in a film, it should have a reasonable length of exposure time, as well as having a well-integrated placement such as audio, visual or audio-visual. Product recognition requires an individual to differentiate or discriminate encountered stimuli from a set of extraneous and possibly distracting stimuli (Dodd & Johnstone, 2000: 143). Products, previously demonstrated by others, should have some defining feature in order to it to be recognised.

Products or product recognition depends significantly on the objective and subjective nature of product placements in media such as films as identified by D'Astous and Chartier (2000: 33). The length of time that a product is shown can be seen as objective in nature and depending on the extent to which a product is placed in a scene of a film, and whether the film attendee could or could not miss the product can be seen as subjective in nature. Products can be built into a film indirectly through creative placements such as outdoor billboards advertising the product or through on-set placements where a product is placed in its natural environment, such as a bottle of Pepsi on a kitchen table. This latter type of placements also adds realism to the product and film (Dodd & Johnstone, 2000: 143).

Depending on the stimuli received during a film, a film attendee may or may not identify different products strategically placed within a film. Six major categories regarding differences in the way in which products were placed in films leading to the recognition of them emerged in an analysis conducted by D'Astous & Chartier (2000: 33). It was found that recognition of products depends on subtlety, length, and integration within the scene of a film, personal judgement, product awareness and the verbal announcement of the product's name within the film.

Previous research by Gupta & Lord (1998: 49) has shown that recall and recognition will be higher when a product placement includes both an audio and a visual compared to that of only a subtle visual usage. Prominent visual placement is where a product is easily identified by its position and size and when it is included in a major scene within a film. A subtle visual placement of the product has a limited time of exposure and is often used as a background prop without audio reinforcement. For example, where a vehicle passes a billboard on a highway and one could only subtly see the advertisement flashing in the background.

This research attempted to evaluate the recognition a film attendee had when viewing a product that is placed prominently.

H1: The likelihood of a film attendee recognising a product placed in a film is higher when the product placement is more prominent.

3.2 Recall

According to Aaker (1996: 10), product recall is a person's ability to recollect product names used in a film that has been viewed. It has been found that a film attendee's recall is higher when a product placement is repeatedly vis-à-vis than when it is shown once. Product recall relates to consumers' ability to retrieve the product from memory given the category, and the needs fulfilled by the product as a cue (Aaker, 1996: 10). Hence, cues such as product categories, a purchase or usage of a product or scenes from a film may aid the recall of those products stored within it (Dodd & Johnstone, 2000: 143). It requires consumers to correctly generate the product from memory when given a relevant cue. Product awareness can provide a host of competitive advantages for the marketer. According to Aaker (1996: 174), three distinct advantages are: it provides the product with a sense of familiarity; the salience of a product will determine if it is recalled at a key time in the purchasing process and product awareness is an asset that can be remarkably durable and thus sustainable. One influencing factor can be a person's memory and recall. Repeated exposure of a product within a film plays an important role, and Balasubramanian (1994: 21) emphasises that recall is considered a crucial gauge of a product placement's effectiveness.

Product association is one of many means that a marketer can use to stimulate their products in the mind of a consumer. According to Bovée, Houston & Thill (1995: 248), product associations can be defined as perceptions and images that people link with particular products. Marketing programmes that link strongly create a positive product image, favourable, unique and admirable associations to the product in the consumer's memory (Keller, 2003: 70). The association attached to a company and its products can therefore be key enduring business assets.

Alba & Chattopadhyay (1986: 363) found that a film attendee's recent and repeated exposure to a product increases its salience and thereby increasing his/her product recall. Product salience is seen as the prominence or level of activation of the product in the memory (Berry & Miller, 1998: 3). All human beings are involved in decision-making processes in their everyday life that incorporates memory processes. Atkinson & Shiffrin (1971: 84) state that incoming information from the external environment travels via the sensory memory into the short-term memory (STM). Salient information is then passed to the long-term memory (LTM) where it can be stored during several minutes or many years (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1971: 84). A film attendee has a greater probability of STM recall if the exposure is recent, whereas the more frequent a film attendee is exposed to the stimulus over time, the greater the chance of recall via LTM.

H2: Repeated exposure to product placements within a film will increase a film attendee's recall.

4. Method

Non-probability convenience sampling was used to select 18 to 24 years old students, at a tertiary institution in Pretoria, South Africa. Respondents were chosen at random, being those students who attended a specific lecture that was on a predetermined date. A sample size of 223 responses realised. The respondents were shown 11 film clips of well-known films. Once these clips had been viewed, they were requested to complete the questionnaires allocated to them. The researchers were present throughout the data collection process, so that queries could have been answered and this was done without intentionally provoking bias. The film clips shown as well as the questionnaires that were completed were all conducted in English.

The use of scenes in a film clip had been selected to help stimulate recall and recognition in the minds of the students. Examples of various products were included in the clip. The first clips shown to the respondents came from the film How to lose a guy in 10 days. The product name is Coca Cola (duration: 36 seconds). The setting is at a refreshment counter at a basketball game. The story: A man runs to the refreshment counter and orders a Coke with no ice. The salesman pitches all the specials offered with Coke. The man gets frustrated and repeats that he wants a Coke with no ice, pays and takes the already poured Coke from the salesman and runs back to the basketball game.

The second product name is People Magazine (duration: 15 seconds). The setting is in a bathroom. The story: A man turns the water on in the shower while conversing with a lady who is seated on the toilet lid. The People magazine is shown from a magazine rack behind her, next to the toilet.

The second film clips came from the film S.W.A.T. The product names are McDonald's and Dr Pepper (duration: 24 seconds). The setting is at a traffic department. The story: Man sitting at a reception desk in the traffic department eating a McDonald's meal. The meal and a Dr Pepper are openly displayed on the desk in front of the man.

The third film clips came from the film Gone in 60 seconds, where Porsche featured (duration: 20 seconds). The setting is in an automobile dealership. The story: Three men drive to the dealership and forcefully enter the display room. They break open the Porsche key storage compartment and proceed to steal a silver coloured Porsche. Relevant non-verbal variable: Breaking open a branded key box and stealing a Porsche. The brand name, Jack Daniels also featured for 30 seconds in a bar setting. The story: The bar lady pours a tot of Jack Daniels, places her hand on top of the bottle while conversing with another man. The man pays for a customers drink and leaves the bar. The customer proceeds to ask for his drink, the bar lady instead drinks it herself.

Kate & Leopold is the fourth film clips that the respondents were exposed to. In the scene Gillette Foamy and Colgate were shown for 31 seconds in a bathroom setting. The story: A man reads the instructions on the bottle of how to use Gillette Foamy shaving cream. He proceeds to follow the instructions.

The fifth clips came from the film What Women Want. In this scene, various products were shown, such as: Anti-wrinkle cream, mascara, moisturising lipstick, bath beads, quick-dry nail polish, at home waxing kit, Wonder Bra, home pregnancy test, hair volumiser, pore cleansing strips, Advil, pantyhose, Visa Card (duration: 22 seconds). The setting is in a boardroom on a table. The story: A lady explains the contents of the beauty kit that each member in the boardroom has in front of them. While she is mentioning each item in the beauty kit, each member analyses the relevant contents.

Just Married was the sixth film clip that the respondents were exposed to. Two scenes were selected. The first was in a bedroom, where Nike was prominent (duration: 10 seconds). The story: A man is busy studying at a desk in his room, while a dog continuously pulls at the man's pants showing his Nike shoes. The second scene featured Pepsi (duration: 21 seconds) in a lounge setting. The story: A man and his father are talking in the lounge with a Pepsi being displayed in front of them on the table.

The seventh clips came from Swordfish. Three scenes were selected depicting Heineken, Smirnoff Vodka, Marlboro cigarettes, Nokia and Yellow Cab. Heineken (duration: 16 seconds) was shown in a "trailer" home setting. The story: A lady opens the fridge in the "trailer" home to take out a refreshment. She proceeds to take one of the many Heineken beers in the fridge and opens and drinks it. Smirnoff Vodka and Marlboro cigarettes (duration: 22 seconds) in a lounge setting. The story: A lady speaks to her former husband over the telephone while smoking a cigarette and pouring herself a glass of Smirnoff Vodka with an empty box of Marlboro cigarettes lying on the table. Nokia and Yellow Cab featured for 16 seconds in another scene on a merry-go-round. The story: A little girl is sitting on a merry-go-round using her Nokia Mobile telephone to call for the number of a Yellow Cab.

The eighth clips, that contained a number of various products, is the film Bend it like Beckham. Playstation, Vodafone, Ford, Amstel Beer, Master Card, and Adidas featured for 36 seconds in a soccer stadium setting. The story: A soccer tournament is taking place, where T-shirts, sponsored by Vodafone, are worn by the soccer players as well as the spectators and the rest of the logo's are found as advertising banners surrounding the soccer field.

In another scene, Lucozade Sport, Adidas and Reebok were shown for 11 seconds in a training session on a sports field. The story: A coach wearing a Reebok sweater is training soccer players. He walks towards a lady sitting in the grand stand above a Lucozade advertising banner and the lady who takes over the exercises is wearing an Adidas top.

Two Weeks Notice was the ninth film clip in which the GQ Magazine was shown (duration: 15 seconds) at a formal business function. The story: Two ladies approach a man and proceed to ask him to sign the GQ Magazine. The last film clips came from The Italian Job. The Mini Cooper was shown in one scene for 16 seconds in an automobile workshop. The story: A man is approached by another who offers him money to open up a storage container that contains Mini Coopers.

Specific products at different prominence and intensity levels were included to test whether this affected the respondent's perception of product placements in film. Lights in the venue were dimmed in an attempt to simulate the cinematic experience.

5. Results

Scenes from the above films were viewed by respondents with the aim of determining the respondents' ability to recall specific products placed therein. "Fake" products were intentionally placed in the question to test the respondents' ability to recall the actual products within the clip.

5.1 Product recognition

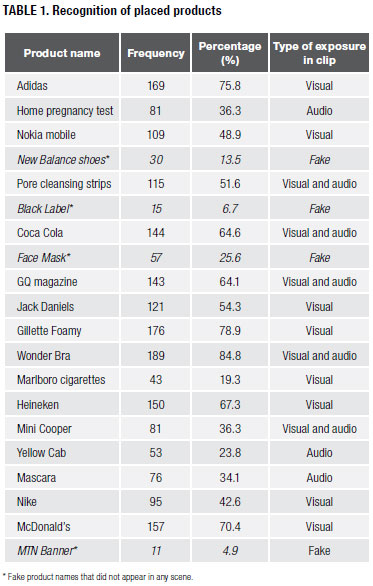

Recognition is determined by how prominent a product placement is in a film scene. This was determined by placing products in two separate categories, namely, prominence and subtlety. Prominence was described as a product being shown audibly and visually, whereas subtlety was described as a product being shown either audibly or visually. In Table 1, the percentage recognition by the respondents is shown for the various products.

The fake product names that did not appear in any scene represented a relatively low percentage of recognition among the respondents. The names of products that were only audible received relatively low percentages as opposed to those products that were visible and those that were both audible and visible to the respondents.

5.2 Product recall

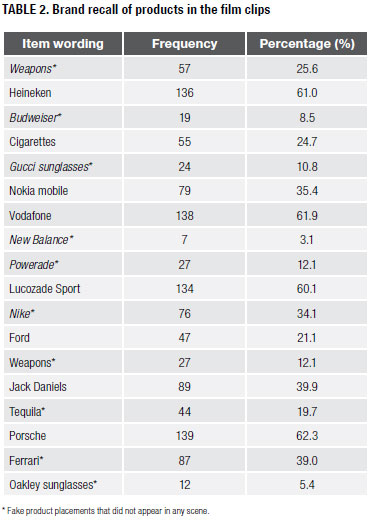

Recall was tested by the ability of the respondents to remember the product names that appeared in scenes from the film clip. Table 2 includes product names that were given to the respondents and they were then asked if they could recall/remember it. The table consists of product names that appeared in the above mentioned film clips.

Sixty one percent of the total respondents recalled viewing Heineken in the film clip, which represented a relatively high percentage of recall among the respondents. This product was repeatedly shown in the film clip. The respondents (27.4%) recalled viewing "cigarettes" in the film clip, which represented a very low percentage of recall among the respondents. This product was repeatedly shown in the film clip. Thirty five percent of the total respondents recalled viewing Nokia mobile in the film clip, which represented a relatively low percentage of recall among the respondents. This product was only shown once off and not repeated in the film clip.

Nearly 62% of the respondents recalled viewing Vodafone in the film clip, which represented a relatively high percentage of recall among the respondents. This product was repeatedly shown in the film clip. Sixty percent of the respondents recalled viewing Lucozade Sport in the film clip, which represented a relatively high percentage of recall among the respondents. This product was repeatedly shown in the film clip. The respondents (21%) recalled viewing Ford in the film clip, which represented a very low percentage of recall among the respondents. This product was repeatedly shown in the film clip. Although the brand name Nike did not appear in the film clip, 34% mentioned that they recall the brand name.

Nearly 40% of the respondents recalled viewing Jack Daniels in the film clip, which represented a relatively low percentage of recall among the respondents. This product was repeatedly shown in the film clip. Sixty two percent of the respondents recalled viewing Porsche in the film clip, which represented a relatively high percentage of recall among the respondents. This product was repeatedly shown in the film clip.

6. Hypotheses testing

A 0.05 level of significance was used in the hypotheses testing.

H1: The likelihood of a film attendee recognising a product placed in a film is higher when the product placement is more prominent.

As there was a relationship between product placements being more prominent and being less prominent, it could be defined as a one-tailed hypothesis. Recognition was tested on whether the item was only shown visually, only mentioned audibly or both audibly and visually in the scenes in a film clip.

H2: Repeated exposure to product placements within a film will increase a film attendee's recall.

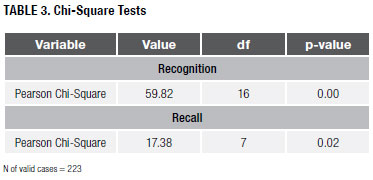

The formulation of this alternative hypothesis stated that there was a relationship or correlation between variables. As there was an increasing relationship between repeated exposure of product placements and that of an attendee's recall, it could therefore be defined as a one-tailed hypothesis. The non-parametric Cramer's V test was considered for this hypothesis to test the strength of the relationship between the repeated exposure of product placements and that of an attendee's recall. As this method only tests for the strength of the relationship, a Chi-Square test had to be conducted to determine the significance level of the variables. As the variable repeated exposure falls into the category of nominal data only a non-parametric test could be used and, for the purpose of this study, the Cramer's V and Chi-Square tests were selected. The Cramer's V test was used to test the strength of the relationship being measured and as it is a non-parametric test no assumptions have to be met. Table 3 depicts the results of the Chi-Square test measuring the two-tailed p-value for the recognition of products as well as the recall thereof within film clips.

There is a significant relationship between the prominence of a product and a film attendee's recognition of a product placed in a film as the p-value was calculated to be 0.00 on a 95% confidence level. There is a significant relationship between repeated exposure of a product and a film attendee's recall of a product placed in a film as the p-value was calculated to be 0.00 on a 95% confidence level.

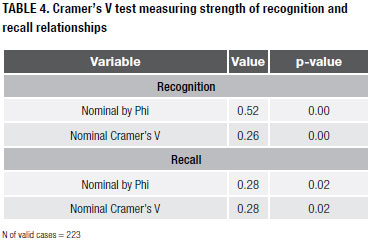

The Cramer's V test measures the strength of relationships. In Table 4, the results for the strength of recognition of product placements as well as recall in the film clips are illustrated.

If the Cramer's V value is 1 there is a perfect relationship between the variables, but this test showed a value of 0.26 and therefore the relationship is relatively weak. The p-value of the Chi-Square test was shown as the significance value for the Pearson Chi-Square from the table above. This value of 0.00 needed to be converted to the appropriate one-tailed p-value, as this hypothesis is directional. To increase the accuracy of the calculation below, the full p-value as calculated in SPSS was used. Since the one-tailed p-value of 0.00 was smaller than the significance value of 0.05, the null hypothesis can be rejected. As shown above in Table 4, it can be concluded that there is a significant relationship between the prominence of a product and a film attendee's recognition of a product placed in a film. It can also be concluded that the strength of the relationship is not very strong as the Cramer's V value was 0.26. The Cramer's V statistic is a measure of the association between 2 variables and takes on values between 0 and 1; with 1 indicating perfect association. It can therefore be concluded that the strength of the relationship is not very strong as the Cramer's V value was 0.26 (Kanfer, 2007: personal E-Mail).

This test showed a value of 0.28 and therefore the relationship is not strong. The p-value of the Chi-Square test was shown as the significance value for the Pearson Chi-Square from the table above. This value of 0.02 needed to be converted to the appropriate onetailed p-value, as this hypothesis is directional. The resultant p-value is 0.01 and is smaller than the significance value of 0.05. The null hypothesis can be rejected and it can be concluded that there is a significant relationship between the repeated exposure of product placements and that of an attendee's recall. The more often and the longer that an attendee is exposed to the product the better their recall and recognition.

7. Limitations of the research

The survey was limited to the products shown in scenes of a film clips that was compiled from ten wellknown feature films that attracted and many young respondents within the given age group. Random selections of brand names that are familiar and used by this target group were selected as stimulus material. A larger sample with specific target characteristics can be considered from numerous other films. The ordinary class situation was not a true experience of the cinema theatre, and the short film clip was also not experienced as a feature film. As a result, the respondents could have been more attentive towards product recognition and recall.

8. Conclusion and recommendations

New technologies, integrated marketing communications and social trends are likely to cause product placement to increase. To fully analyse these changes and implement marketing strategies thereof, benchmark studies are needed. In that context, the present research might establish a benchmark regarding perceptions of product placements with regard to product recognition and product recall of products placed in a film. The findings show that even though there is not a perfectly positive relationship between prominence and recognition of products placed in films, a film attendee is more likely to recognise a product if it is shown audio-visually than if it is only shown either audibly or visually. Film attendees' ability to recall a product is shown to be more likely, if the product is repeatedly shown throughout the film than if it is only shown once. The relationship between recall and repeated exposure is not perfect, but it is positive. The following recommendations can be considered.

Marketers can place their products in films to increase film attendees' awareness and recognition, but as it was found that there is not a very strong relationship between recognition and prominence of products in films, recognition does not necessarily increase in proportion to whether the product is placed audibly, visually or audio-visually. A product is more likely to be recognised if it is prominently shown through audio and visual means.

Marketers can place their products repeatedly in films to increase awareness and recall of film attendees, but the number of times the product is repeated does not necessarily indicate the number of times the film attendee will recall it. A product is more likely to be recalled if it is shown repeatedly than if it is only shown once off.

For future research, marketers should take into consideration that only a few factors were discussed in this study to determine a film attendee's perceptions of product placements within films, namely, product recognition and product recall. Marketers can break the clutter of advertisements in traditional media, by strategically placing products in new, more unconventional media as to complement the marketing strategy. Product placement as a solo marketing effort with little integration into the IMC strategy of the organisation is worthless. It is recommended that marketers could also include the following variables to broaden the investigation of this topic thereby having a deeper understanding in this regard:

- Realism could be investigated to determine whether product placements make films seem more realistic, as well as the cinematic experience more true to life.

- Product awareness could be more specifically focused on with the intention of shedding more light of the perception film attendees have with regard to product placement in films as a captive audience with little influence from external noise.

- The impact of product placements in the escalating mobile media usage should be investigated.

- The rise of citizen-generated media on Youtube, product placement based sponsorship of citizen media is going to be an issue for marketing, legislators and academics to pursue further.

- A larger and more heterogeneous sample can be used which is more representative of the South African population. A sample that will include more ethnic groups can be considered as a main variable in a study surrounding the perception of product placements in films. All age groups should be considered with the aim of determining different perceptions that specific ethnic groups have towards product placements in films. This is paramount in a country with more than 11 official languages and more than 23 distinctive and homogeneous cultural groupings.

- A film attendee's intention to purchase a product once it has been viewed in a film can be explored by researchers as to detect the causal impact of the exposure to the product and the purchase thereof.

- Brand salience is another factor that can be included in future surveys.

Bibliographical references

Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building strong products. London: the free press.

Alba, J. W. & Chattopadhyay, A. (1986). Salience effects in product recall. Journal of Marketing Research, 23(4), 363-369.

Atkinson, R. C. & Shiffrin, R. M. (1971). The control of short-term memory. Scientific American, 224, 82-90.

Balasubramanian, S. K. (1994). Beyond advertising and publicity: hybrid messages and public policy issues. Journal of Advertising, 23(4), 1-21. Retrieved June 14, 2004, from http://weblinks1.epnet.com/citation.asp?tb=1&_ua=%5F2&_ sid+92317498%2D8

Belch, G. E. & Belch, M. A. (2001). Advertising and promotion: An integrated marketing communications perspective (5th ed.). New York: mcgraw-hill.

Berry, L. & Miller, S. (1998). Product salience versus product image: two theories of advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research, 12(2), 1-11.

Bovée, C. L., Houston, M. J. & Thill, J. V. (1995). Marketing (2nd ed.). London: McGraw-Hill.

CBC Arts Online. (2006). Product placement report. Retrieved August 30, 2006, from http://www.cbc.ca/story/arts/national/2006/08/20/productplacementreport.html?ref=rss

Cohen, N. (2006). Virtual product placement infiltrates TV, news, games. Retrieved August 18, 2006, from http://www.ecommercetimes.com/story/48956.html/

D'astous, A. & Chartier, F. (2000). A study of factors affecting consumer evaluations and memory of product placements in movies. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 22(2), 31-40.

Delorme, D. E. & Reid, L. N. (1999). Moviegoers' experiences and interpretations of products in fi lms revisited. Journal of Advertising, 28(2), 1-30. Retrieved March 6, 2004, from http://weblinks3.epnet.com/citation.asp?tb=1&_ug=dbs+buh+sid+33E64EB3%2DB13D

Dodd, C. A. & Johnstone, E. (2000). Placements as mediators of product salience within a UK cinema audience. Journal of Marketing Communications, 6,141-158.

Ebscohost. (2008). Accessed January 13, 2008, from http://0-ejournals.ebsco.com.innopac.up.ac.za/Home.asp

Emerald. (2008). Accessed January 13, 2008, from http://0-www.emeraldinsight.com.innopac.up.ac.za/

Fill, C. (2002). Marketing communications: contexts, strategies and applications (3rd ed.). London: Prentice Hall Financial Times.

Gould, S. J., Gupta, P. B. & Grabner-Kräuter, S. (2000). Product placements in movies: a cross-cultural analysis of Austrian, French and American consumers' attitudes toward this emerging, international promotional medium. Journal of Advertising, 29(4), 41-58.

Gupta, P. B. & Lord, K. R. (1998). Product placement in movies: the effect of prominence and mode on audience recall. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 20(1), 47-59.

Hornick, L. A. (2006). The evolution of product placement: consumer awareness and ethical considerations. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://eidr.wvu.edu./eidr/documentdata.elDR?documentid=4542-8k-/

Kanfer, F. H. J. (2007, august 28). Cramer V (personal e-mail). Department of Statistics, University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Keller, K. L. (2003). Strategic product management: building, measuring and managing product equity (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: prentice-hall.

Mcdaniel, C. & Gates, R. (2001). Marketing Research Essentials (3rd ed.). Cincinatti, Oh: South-Western College.

Mckechnie, S. A. & Zhou, J. (2003). Product placement in movies: a comparison of Chinese and American consumers' attitudes. International Journal of Advertising, 22, 349-374.

Nelson, M. R. & Mcleod, L. E. (2005). Adolescent product consciousness and product placements: awareness, liking and perceived effects on self and others. International Journal of Consumer studies, 29(6), 515-528. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://0-www.blackwell-synergy.com.innopac.up.ac.za/doi/full/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2005.00429.x

Russell, C. A. (2002). Investigating the effectiveness of product placements in television shows: the role of modality and plot connection congruence on product memory and attitude. Journal of Consumer Research, 29, 306-318.

Schejter, A. M. (2004). Product placement as an international practice: Moral, legal, regulatory and trade implications. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://www.web.si.umich.edu/tprc/papers/2004/304/productplacementtprc.pdf./

Sabinet. (2008). Accessed february 7, 2008, from http://0-search.sabinet.co.za.innopac.up.ac.za/

Science Direct. (2008). Accessed January 16, 2008, from http://0-www.sciencedirect.com.innopac.up.ac.za/science?_ob=BrowseListURL&_type=subject& subjColl=14& zone=brws&_acct=C000005298&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=59388& md5=6dcfe4cc6b2182dfdade5ff066154ef0

Smith, B. (1985). Casting Product for special effect. Beverage World, 104, 83-91.

Source Watch. (2006). Product placement. Retrieved August 28, 2006, from http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=Product_placement

Van der Waldt, D. L. R. (2005). The role of product placement in feature films and broadcast television programmes: an IMC perspective. Communicare, 24(2), 1-16.

Vollmers, S. & Mizerski, R. (1994). A review and investigation into the effectiveness of product placement in films. In K. W. King (ed.), The Proceedings of the 1994 Academy of Advertising Convention (pp. 97-101). Athens, GA: University of Georgia.

Wiles, M. A. & Danielova, A. (2006). The impact of product placement on firm market value. Retrieved September 1, 2006, from http://kelly.iu.edu/marketing/