My SciELO

Horizontes Antropológicos

Print version ISSN 0104-7183

Horiz.antropol. vol.3 no.se Porto Alegre 2007

Extreme messianism. The Chabad movement and the impasse of the charisma

Enzo Pace

University of Padova – Italy

Replicated from Horizontes Antropológicos, Porto Alegre, v.13, n.27, p.37-48, Jan./June 2007.

ABSTRACT

The article deals with the social construction of the charisma of the seventh leader (rebbe) of the Jewish Chabad movement, Menachem Mendel Schneerson (19021994). The comprehensive analysis of the charismatic carrier of the leader shows the process by which the spiritual power of Schneerson moved from a classical (according to Weber) interaction between charisma and a community that recognizes this power to a identification of his figure with the Messiah. Schneerson and the Chabad movement actually represent an effort to modernize one of the two tendencies present in the Chassidic tradition concerning the figure of Messiah: in contrast with the idea that considers not predictable the arrival of Messiah, Chabad, particularly because of the Schneerson's charisma, believe the advent of Messiah imminent. The task of the leader consequently is to pay attention on the premonitory signs of the forthcoming event. The identification between charisma and Messiah in Chabad movement represents a case study of extreme messianism that means a real impasse to solve and rule the question of succession of charisma after the death of the Rebbe.

Keywords: charisma, messianism, Chassidic tradition, Ultra-orthodox Judaism.

RESUMO

Este artigo trata da construção social do carisma do sétimo líder (rabino) do movimento judaico Chabad, Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-1994). A análise compreensiva da carreira carismática do líder mostra o processo pelo qual o poder espiritual de Scheneerson deslocou-se de uma clássica (de acordo com Weber) interação entre carisma e uma comunidade que reconhece esse poder pela identificação da figura de Schneerson com o messias. Scheneerson e o movimento Chabad realmente representam um esforço para modernizar uma das duas tendências presentes na tradição chassídica concernente à figura do messias: em contraste com a idéia que considera não previsível a chegada do messias Chabad, particularmente por causa do carisma de Schneerson, acredita que o advento do messias está iminente. A tarefa do líder conseqüentemente é prestar atenção nos sinais premonitórios do evento futuro. A identificação entre carisma e messias no movimento Chabad representa um estudo de caso de extremo messianismo que significa um real impasse para revolver e regular a questão da sucessão do carisma depois da morte do rabino.

Palavras-chave: messianismo, carisma, judaísmo ultra-ortodoxo, tradição chassídica.

They said the Messiah was coming, and many members

of the Chabad religious movement believed it and

arrived at the Tel Aviv basketball stadium to greet him.

Their Messiah is supposedly the late Rabbi Menachem

Schneerson… According to some, if all the Jews of

Israel kept two full Sabbaths, then the Messiah would

show up. I think we have a long wait.

(www.chabad.org)

The messianism as idea-typus

The subject of my paper is messianism as a type of socio-religious action within the context of modern Judaism. As a concept, messianism often takes the form of a collective movement based on religion. It is therefore a symbolic resource mobilized by collective subjects in the process of constructing their own identity and in order to ensure their social success. From the sociological viewpoint, two of the most interesting aspects of the messianic phenomenon are the identity and organizational performances of the religious movement. From this perspective, messianism comes within Weber's ideal-type of charismatic action, since it presupposes the appearance of a virtuoso of social redemption, i.e. a subject able to interpret the waiting for change. Because he has yet to come and be recognized, it is of no importance whether this figure is still faceless or a flesh-and-blood person. In sociological terms, messianism is an organized way of believing that creates real, effective social bonds, in alternative to the constituted social order. Here, we are only marginally interested in reviewing the notion of messianism as such; rather what interests us is to attempt to measure the social effects it produces, when it becomes the chief concern in a system of belief. We prefer to see it here as a means of communication which is gradually changing within a socio-religious movement into a fully-fledged collective narrative. For instance, if the Messiah has already come or his arrival is imminent, a movement that believes in this proposition tends to transfigure the particular into the universal, going beyond the distinction between the life of the individual and that of society, including everyday life, in order to create moral and religious unity. Thus, even when it points to a belief in the world to come, messianism helps reformulate social bonds here and now; in a word: it creates society. The problem for sociologists is therefore to discover through investigation and analysis what type of social order is established: the model of authority experienced, the social relations set up, the interactive rituals and lastly the social outcome produced by organizational performances (both in terms of reproduction of the organization which the messianic movement gives rise to and in more practical terms, e.g. the mobilization of human and financial resources). We will concern ourselves here with a particular case: the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, which forms part of the Chassidic (mystical) branch of modern Judaism (dating back to seventeenth century central and eastern Europe).

Two currents in Jewish Messianism

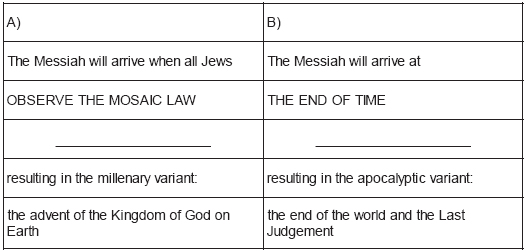

Before briefly outlining the characteristics of this movement with its headquarters in Crown Heights, New York, it is worth summarizing the various conceptions of messianism in Judaism. Reducing to a thumb-nail Gershom Scholem's (Idel, 2004; Scholem, 1993) important work on this subject, we offer the following diagram:

Because the coming of the Messiah was no longer deemed imminent, at the end of the eighteenth century both interpretations were superseded by the notion of being at the service of God in exile.

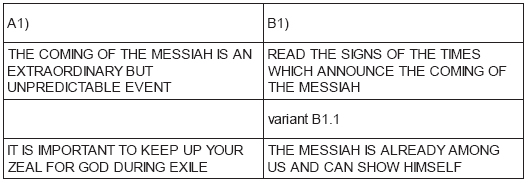

After the Shoa, the distinction between the two orientations was reestablished:

These two conceptions, which differ as to the nature of messianic redemption, are to be found again in the discussion which took place (and which is still hotly debated) between the rabbis of the various schools of thought. Opinions range from those who associate the coming of the Messiah with merit and those who believe that not everything depends on the moral perfection of Man, and therefore external intervention is required to help Man overcome his limitations. Through these conceptual developments, we catch a glimpse of the two different notions of messianism: the first considers the messianic era an event that the action of Man can either hasten or delay; the second considers the coming of the Messiah an unconditional event, sudden and gratuitous, that bursts in on history from the outside and totally transforms it. One of the greatest thinkers of our times, Levinas (1961) pondered at length on this question. In the end, he opted to side with those who maintain that the messianic age coincides with mankind's hopes to see the historical triumph of the end of violence and the establishment of a society founded on justice. What interests the French philosopher is the intersubjective dimension (the Other, one's neighbour), encompassing the notion of messianism. "The age of the Messiah", according to Levinas, distinguishes itself from "the future world" because it needs the "fecundity of time"; it is not the equivalent of the liberation of time, yet it takes place in time (Levinas, 1974). Thus, messianism may be linked to a charismatic figure, but it performs an ethical-social function; it establishes a social order which prefigures the waiting for salvation.

The messianism of the Chabad movement

What distinguishes the Chabad movement from Levinas' interpretation is not so much the ethical-social dimension that the movement in question has expressed over the last thirty years, but rather the emergence of a figure who has gradually managed to gain credence not only as a charismatic leader (which is nothing particularly new in the Chassidic tradition), but also – and perhaps this went beyond the intentions of the last spiritual head of the movement, who died in 1994 - as the Messiah, the bearer of an extraordinary personal gift. Menachem (in Hebrew: the consoler), is in fact an attribute associated with one who feels a messianic vocation but it is also the name of the late leader of Chabad. Finally, it should be remembered that the Hebrew term mashiach (from which the Greek word messias is derived) really means "anointed" and occurs in the Old Testament as the attribute of most of the kings of Israel or Judea (ha-melekh ha-mashiach, "the anointed king"). At the time, anointment was the equivalent of enthronement (compare for example the anointment of David, recounted in 1 Sam 16, 3-12). Later, mashiach was also used with reference to priests, patriarchs and prophets, as anointment came to indicate consecration. Only with the post-exile epoch, and then in late Judaism, did the term mashiach assume an eschatological meaning to indicate someone invested with a divine mission, summoned to fulfil a promise of liberation or salvation. Chabad is an acronym derived from the first letters of Hebrew words: Hochmah (wisdom), Binah (understanding), and Da'at (knowledge). The movement began in a small town in Belarus, called Lubavitch, around the figure of the first rebbe (charismatic leader) Schneur Zalman from Liadi (1745-1813). The movement forms part of a larger network of Chassidic communities (or courts) (chassidim meaning 'the pious' in Hebrew), composed of a number of families. Originally, these families traced their common descent from a charismatic leader who transmitted his extraordinary powers "through the blood". The leader of a Chassidic court is considered a mediator between the "celestial court" and the "earthly" one. Thanks to his exceptional powers of sanctity, the leader is able to put the human community in communication with the world of the divine. At the same time, he has often been seen as a spiritual master and healer, the community's political leader and the bearer of a special gift, the ability to perform miracles (mofsin), and ward off misfortune. Because of this concentration of extraordinary powers, the Chassidic communities chose to call their leaders rebbe, rather than use the traditional name of rabbi.

The charismatic leadership of the Menachem Schneerson

The last rebbe of the Chabad movement was Menachem Mendel Schneerson. His views form part of the Jewish Messianic school of thought which sees redemption as a public event which will occur in history and arise within the community of the pious who await the Messiah. The community is therefore a sort of living laboratory from which the face of the Messiah will emerge. The Messiah in question is Ben David, of whom Schneerson often spoke, as an eschatological but at the same time real figure, in whom all the new ideas of the Last Times will appear. This concept not only helps strengthen the authority of the charismatic leader – easily identifiable by his holiness and exemplary nature with the Messiah to come –, but also represents a strong cohesive factor for the group, exalting the special virtues of which he is the embodiment, the vanguard of the central event in the messianic belief. This explains the particularly important effects on organizational performances, both as regards the missionary zeal which guides the movement's collective action, and as regards the authority structure of the relationship between master and followers. If you are convinced that the Messiah is "amongst us", then the intensive activity of proselytism, which is not traditionally widespread in Judaism, can be justified. Furthermore, if this conviction is continually enhanced by the process of beatification or sanctification "on earth" of the figure of the charismatic leader carried out by the community and seconded by the leader, messianism becomes a symbolic resource with a high organizational value. When Schneerson was nominated in 1951 as the legitimate successor to the 6th rebbe (Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn), in his inaugural speech he stated that:

This generation will announce the Age of the Messiah", bringing to an end the teshuvah, the penitence which pre-announces the coming of the Messiah. (see official website of the organization).

The decision he made on the occasion of the Six-Day War in 1967 to send spiritual assistants from the movement to the soldiers at the Front was based on a precise eschatological conviction. By so doing, in fact, he rehabilitated in the eyes of many ultra-orthodox Jews abroad the theological legitimacy of the State of Israel, which had until then been considered an unholy, artificial creation by many movements. The argument he used to persuade his followers was that by winning the war the holy borders of the Promised Land (Eretz Yisrael) would be re-established in their entirety. Such an event would confirm the imminent arrival of the Messiah. The messianic wait was therefore linked to a series of events which were practical and not imaginary. From that moment on, the movement was urged by the Rebbe to engage in an intensive campaign of re-Judaization in the neighbourhoods of Brooklyn. He launched the idea of what came to be called mitzvah tanks, i.e. "tanks of the commandments", groups of proselytizing missionaries in minibuses working the streets of the metropolis. In 1989, he assured his followers that the age of the Messiah was imminent: "the obscurity of golus (exile) is about to be transformed into Light". This prediction, based on a Kabbalistic interpretation, enabled him to explain both the reestablishment of Eretz Yisrael and the collapse of the Berlin Wall. The announcement was interpreted by his followers as an explicit reference to the role of the rebbe as a visible link between the Earthly Court and the Celestial one, between the community of the pious on Earth and the Messiah above. Despite the numerous conflicts with other Chassidic courts (the Satmar court, for example) which accused Chabad of being a personality cult, the messianic function of Schneerson's leadership was boosted by the dramatic events which affected Israeli society. During the Gulf War of 1991, for example, the Rebbe prophesied that nothing would happen to the Children of Israel. With the defeat of Iraq and the relatively little war damage to Israel, he gained a reputation as a credible prophet, and not only among his own followers; many chassidim were reported to have left other courts for the Chabad one. Interest in his sanctity and extraordinary powers grew steadily. On his death in 1994, the process of mourning amongst his followers proved long and complex for two main reasons. In the first place, many believed, and still believe, that he was the Messiah; hence the problem of explaining his disappearance from the Earth. Secondly, there was the difficulty of finding a successor to his charisma. If Menachem is the Messiah, no-one can succeed him. But then who will take on the guiding role in the community? It is no accident that the place where the Rebbe is buried is called ohel (literally "the tent"), and is visited by a constant stream of pilgrims. The force of his messianic and charismatic power is allegedly still active (Abramovitch; Galvin, 2002; Allouche-Benayoun; Podselver, 2003; Bauer, 1998; Brodowicz, 1998; Ehrlich, 2000; Feldman, 2003; Greilsammer, 1991; Guolo, 2000; Gutwirth, 2004; Mintz, 1992; Pace, 2003; Pace; Guolo, 2000; Ravitzky, 1996).

Messianism as an organizational culture

In many ways, the messianic tension of Chabad recalls the Ernst Bloch's well-known theory on the revolutionary theology of Thomas Münzer (Bloch, 1981). In one extraordinarily effective passage, Bloch compares Anabaptist millenarianism with the Jewish Kabbalistic Messianic movement, Safed, which awaits the end of impiety on Earth and the coming of a new kingdom resplendent with the power of the Lord (Löwy, 1998). Applying Bloch's theory, we could say that Chabad represents a variation of revolutionary messianism for the following reasons:

a) it keeps alive the memory of the exodus – the uprooting and Diaspora of the Jews – which fuels the desire to return to the Promised Land;

b) the Promised Land has, in fact, still to be redeemed, since the State of Israel is an unsound political creation, having no basis in the Torah; it is suspended in indefinite time, awaiting the Messiah, who will finally materialize in the form of the Rebbe;

c) in the meantime, social and religious action must enable people to really imagine what it means to live as if the Messiah had come, prefiguring here and now the possibility of changing the social structure and power relations.

The Chabad communities are utopian in character; they believe in the practice of equality and fraternity in contrast to a social and political structure which they perceive as impious and unjust. The ideological device – the firm belief in the imminent coming of the Messiah – does not give rise to a withdrawal from the world. On the contrary, it mobilizes human, material and organizational resources to transcend reality and prefigure those times, when the world will no longer be as alien as it appears today to the vanguard of pure faith. This is how the followers of Chabad see themselves, in contrast to their religious brethren who, in their view, have become secularized.

In 1949, Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn, then head of the Chabad community, decided to create a small self-sufficient village in Israel called Kfar Chabad (which grew from 1,540 inhabitants in 1969 to approximately 3,500 in 2003). This caused a considerable shift of opinion: previously the State of Israel and Zionism had been considered unholy. After the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Menachem stated that Israel had the full (divine) right to annex the occupied territories, according to the principle of pikuach nefesh. Literally, this means "respect for life", but in the present context, it is the rabbinical expression applied to the essential duty to save the life of a Jew when it is under threat, even if it means breaking Judaic law.

The fact that the Chabad movement came to believe that the seventh rebbe was the Messiah meant that tension in the community was kept high. It also charged up the wait for imminent change in the social order, in particular in Israel, the last frontier of the manifestation of the Messiah and, at the same time, the waiting for the building of a celestial Jerusalem. From 1980 on, the messianic tension within the movement became more pronounced and expressed itself in ever more zealous forms. At the beginning of 1990, Chabad launched a campaign in the major American newspapers to announce the coming of the Messiah. At the same time, they organized the mass distribution of leaflets and stickers bearing the slogan: "we want Messiah now, we don't want to wait". On June 19th 1991, the New York Times carried a Lubavitch advertisement which ran: "the mass return of Jews to the land of Israel from the former Soviet Union and the defeat of Iraq after the first Gulf War are unequivocal signs of the coming of the Messiah". In this climate, the followers of Chabad consolidated their conviction that the seventh rebbe was, in fact, the long-awaited Messiah. In truth, Schneerson never proclaimed himself to be the Messiah, but, on the other hand, he did little to counter this belief. In April 1992, a group of Lubavitch rabbis made an authoritative statement in which they identified the messianic traits of Rebbe Schneerson (Ravitzky, 1996, p. 205), provoking criticism from within the movement itself by other more cautious rabbis who had misgivings about the identification of the figure of the Messiah with the head of the movement. When their leader died at the venerable age of 92 in the summer of 1994, many of the faithful continued to believe that he was the Messiah and that, in fact, he was not really dead, and would soon become visible again after his imminent resurrection. Certain rabbis who were fond of the Kabbalah took delight in indicating other signs of Schneerson's messianic profile using numerology. One of them, Butman, pointed out that the number 770 indicated the house of the Messiah in the Kabbalah, and that the Rebbe's abode was 770 Eastern Parkway, Crown Heights!

This belief in the resurrection of the Rebbe prompted other Chassidic communities, always critical of the Chabad movement, to say that the movement was not very kosher, because its non-orthodox beliefs at times bordered on Christian eschatology.

Ten years after the Rebbe's death, the messianic belief is still very much alive. Its missionary zeal provides ample proof of this: the movement has grown by 30% in ten years and can boast approximately 3,000 missionaries in 107 countries around the world.

Chabad Messianism thus represents a sort of symbolic capital which has accumulated thanks to the charismatic force of the leader, who became, in his lifetime, a cultural resource for the organization which has helped make the Chabad movement active and competitive in the contemporary Jewish religious market.

Conclusion

Chabad, therefore, represents a form of extreme messianism capable of mobilizing its militants to perform a type of social action which is rational and undoubtedly oriented toward the affirmation of religious values. However, it is also a means to an end: if the age of the Messiah has come, its announcement must know no limits. The Movement is thus authorized to push the tradition to the very limits, inventing new and innovative repertoires of religious action and narratives. At the same time, the announcement of the Messiah cannot rest or accept compromises, especially not in Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel, that extraordinary place in the universe which is both real and symbolic. The radical position taken by Chabad on the question of the territory occupied by the Israeli army after the wars of 1967 and 1973 is highly indicative. The restitution of even the smallest part is perceived not only as an attack on the "lives of the children of Israel" (according to the principle of pikuach nefesh), but also as an intolerable delay in the coming of the Messiah, or rather, as incredible blindness on the part of the Jews with regard to the clear signs of the imminent revelation, now that finally the borders of the Land of Israel are again those drawn up by the will of God in the Pact of Alliance.

In this case, messianic extremism is a form of inner-world ascetism which ensures the Chabad movement not only social success and a relatively efficient organization, but also a type of rational action: extremism becomes a factor of rationalization in individual and collective life. Thus, it enables the movement to better achieve the goal for which it was formed and for which it was transformed under the seventh rebbe. From being a mystical community of pious chassidim, it has become a successful modern charismatic enterprise on the market of symbolic and religious goods, able to compete with other socio-religious subjects in the same social environment.

References

ABRAMOVITCH, I.; GALVIN, S. (Ed.). Jews in Brooklyn. London: University Press of New England, 2002.

ALLOUCHE-BENAYOUN, J.; PODSELVER, L. Les mutations de la fonction rabbinique. Paris: Observatoire du Monde Juif, 2003.

BAUER, J. Les partis religieux en Israël. Paris: PUF, 1998.

BLOCH, E. Thomas Münzer teologo della rivoluzione. Milano: Feltrinelli, 1981.

BRODOWICZ, S. L'âme d' Israël. Paris: Edition du Rocher, 1998.

EHRLICH, A. M. Leadership in the Habad Movement. Jerusalem: Jason Aronson, 2000.

FELDMAN, J. Lubavitcher as Citizens. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003.

GREILSAMMER, I. Israël: les hommes en noir. Paris: Presses de la Fondation de Sciences Politiques, 1991.

GUOLO, R. Terra e redenzione. Milano: Guerini e Associati, 2000.

GUTWIRTH, J. La renaissance du hassidisme. Paris: Odile Jacob, 2004.

IDEL, M. Mistici messianici. Milano: Adelphi, 2004.

LEVINAS, E. Totalité et infini: essai sur l'extériorité. Paris: LGF, 1961.

LEVINAS, E. Autrement qu'être ou au-delà de l'essence. Nijhof: Kluwer Academic, 1974.

LÖWY M. Redemption and Utopia. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

MINTZ, J. R. Hasidic people in the New World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

PACE, E. Perché le religioni scendono in Guerra. Roma-Bari: Laterza, 2003.

PACE, E.; GUOLO, R. I fondamentalismi. Roma-Bari: Laterza, 2000.

RAVITZKY, A. Messianism, Zionism and Jewish Religious Radicalism. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1996.

SCHOLEM, S. Le grandi correnti della mistica ebraica. Torino: Einaudi, 1993.

Received on 30/10/2006

Approved on09/01/2007