My SciELO

Dados

Print version ISSN 0011-5258

Dados vol.5 no.se Rio de Janeiro 2010

Advantages of immigrants and disadvantages of Afro-Brazilians: employment, property, family structure and literacy after abolition in western São Paulo state*

Vantagens de imigrantes e desvantagens de negros: emprego, propriedade, estrutura familiar e alfabetização depois da abolição no oeste paulista

Avantages de l'immigrant et désavantages du noir: emploi, propriété, structure familiale et alphabétisation après l'abolition de l'esclavage dans l'ouest de l'état de São Paulo

Karl Monsma

Professor of Sociology, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul

Translated by Karl Monsma

Translation from Dados – Revista de Ciências Sociais, v. 53, n. 3, 2010, pp. 509-543.

ABSTRACT

Based on data from a municipal census in 1907, this study compared the situations of Blacks, White Brazilians, and various immigrant groups in early 20th century Western São Paulo. Contrary to assertions in the literature, many Black families were small coffee farmers, and Blacks competed with Europeans in various other manual occupations. Meanwhile, Blacks were almost completely absent from the elites, and literacy rates were extremely low among Blacks, including in the new generation, born after Abolition. The study analyzes the advantages and disadvantages of these various groups, thereby contributing to new hypotheses on the consequences of large-scale European immigration for the Black population.

Key words: immigrants; Blacks; racism; post-Abolition

RÉSUMÉ

À partir d'un recensement municipal, on compare les situations de Noirs, de Brésiliens blancs et de divers groupes d'immigrants dans l'ouest de l'État de São Paulo en 1907. Contrairement à ce que dit la littérature, de nombreuses familles noires travaillaient comme colons du café et les Noirs disputaient avec les Européens certaines occupations manuelles. Par ailleurs, on vérifie l'absence presque totale de Noirs parmi les élites ainsi que des taux d'alphabétisation très bas chez eux, y compris dans la nouvelle génération née après l'abolition de l'esclavage. En montrant les avantages et désavantages vécus par les groupes répertoriés, cette recherche aide à l'élaboration de nouvelles hypothèses sur les conséquences de la grande immigration sur la population noire.

Mots-clé: immigrants; Noirs; racisme; après-abolition

INTRODUCTION

There is relative consensus in the literature on the post-abolition period in São Paulo State that competition from immigrants excluded black people, especially freedpeople, from the most important productive activities. According to the standard account, immigrants rapidly monopolized the family colono contracts on the coffee plantations. This is important because colono families did most of the work of tending the coffee trees and picking the coffee, and this occupation provided some opportunities to save money and aquire land or urban properties. Immigrants, by this account, also monopolized the skilled crafts, leaving black people with only unstable, poorly paid and little respected jobs such as domestic service, street vending, and auxiliary work on the coffee plantations, such as clearing land or repairing fences and roads.

In explanations for the advantages of immigrants, recent authors generally disagree with the older arguments of Florestan Fernandes (1978) and others (cf. Beiguelman, 1978:114-115; Costa, 1999:341; Durhan, 1966:28-29), who affirm that libertos (freedpeople) were poorly prepared to compete with immigrants because the violence and dehumanization of slavery had left them anomic, lacking strong family and community ties, without internal discipline and tending to identify liberty with the absence of work. The current literature places more emphasis on discrimination against libertos and other blacks. Due to the racist stereotypes of the time, which portrayed blacks, especially libertos, as lazy, treacherous, perverted and prone to drunkenness, and European immigrants as hard working, sober and obedient, planter and other employers, according to these authors, almost always preferred immigrants over blacks (Dean, 1976:172-173; Hasenbalg, 1979:165-167; Holloway, 1980:63; Maciel, 1997; Santos, 1998; Wissenbach, 1998). George Reid Andrews (1991:81-85) presents a more nuanced version of this argument, claiming that, in addition to the racism of planters, immigrants monopolized the colono contracts because they accepted family work, whereas blacks rejected female and child labor in the coffee groves, which reminded them of some of the worst aspects of slavery.

This debate does not concern only the state of São Paulo. The consequences of mass immigration were particularly evident in São Paulo because it received many more immigrants that any other Brazilian state, which allows investigation of tendencies for racial discrimination which may have existed in more subtle or veiled form in other states with less immigrants. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, São Paulo also emerged as the most populous, wealthy and powerful Brazilian state. Racial discrimination and inequality in this state had national repercussions, which operated through the economic opportunities open or closed to black migrants from other states, São Paulo's influence on national public policies, and the wide diffusion of São Paulo's cultural products. Finally, São Paulo and other Brazilian regions that received large numbers of immigrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries constitute exceptional cases, in which poor immigrants and their descendents rapidly gained economic positions better than those of most of the native population of the receiving regions. Understanding how this happened can help refine theories of migration processes and racial and ethnic inequalities.

Representations of mass immigration and the post-abolition situation of blacks are also important to current Brazilian debates about affirmative action and racial quotas, especially in universities. The idea that immigrants were privileged in relation to libertos and other Afro-Brazilians is a key part of many arguments for affirmative action as a form of reparation for the cumulative racism suffered by black people over the course of Brazilian history. To advance this debate, it is important to specify exactly what kinds of privileges immigrants received, and the consequences of this for Afro-Brazilians.

There is a paucity of sources allowing systematic comparison of black and immigrant social positions in the first few decades after the final abolition of 1888 because with abolition the Brazilian state stopped including information on color in most official data, attempting to eliminate racial discrimination, or deny its existence, by eliminating information about race. As a result, the arguments cited above regarding black marginalization after Brazilian abolition generally rely on circumstantial evidence and plausibility. Various studies of slavery provide evidence that the ex-captives valued autonomy, wanted to avoid closely supervised collective work and detested the physical punishment of women and children by plantation owners and their agents (Machado, 1987, 1994; Rios and Mattos, 2004). We also know that planters were racists, that their hatred, fear and resentment of blacks increased with the rebelliousness and collective flight of slaves during the 1880's, and that many believed that immigrants were better workers, largely because they were more submissive (Azevedo, 1987; Monsma, 2005). Perhaps more importantly, the supposed economic marginalization of Afro-Brazilians in the post-abolition period serves as an explanation for the continued poverty of the black population in subsequent decades and the greater degree of social mobility observed among the descendents of immigrants. Blaming the racism of elites and policies promoting immigration for later racial inequalities is also a convenient manner to avoid investigation of racist tendencies among immigrants themselves and their descendents, who soon constituted the majority in much of western São Paulo state and, a few decades later, gained economic and political dominance in many municipalities (Truzzi and Kerbauy, 2000).

But the thesis of black marginalization is not completely consistent with the known sources. Forestan Fernandes (1978:31-34) presents mixed evidence. First, he cites documents from the time stating that many libertos continued working on plantations, or went back to work after a few months of absence, perhaps moving to another plantation. Then he cites interviews with the descendents of masters and slaves affirming that planters did not readmit libertos who had left or even evicted all of the libertos from their properties. The police correspondence and criminal trial records from western São Paulo show that there were blacks working as colonos on the plantations, and others in various urban occupations. (Monsma, 2005, 2006). In the municipality of São Carlos, more that two thirds of the ex-captives of the Fazenda Palmital remained on the property in 1889 (Truzzi, 2000: 56). It appears that many blacks were able to compete with immigrants. The preference for immigrants varied from one plantation to another: some planters expelled all former slaves, but others continued to employ them. With respect to libertos, it is important to emphasize that the family work of colonos allowed greater day-to-day autonomy than had gang labor under slavery. The colono contracts, under which heads of households supervised family labor and received payment for the entire family, also reinforced the patriarchal male family heads, whereas slavery had tended to undermine it (Stolcke, 1988: xv-xvi, 17-19).

This article compares the situation of blacks, white Brazilians and different immigrant groups in the municipality of São Carlos in 1907, when this municipality in the west-central region of São Paulo carried out a local census. This census is an extremely rare and valuable source because it includes the variable "color", which was excluded from the great majority of censuses and other official documents in the first few decades after abolition.1 Linking this census to the state agricultural census of 1904-5, it is possible to compare the different groups with respect to occupation, access to property, family structure and literacy. The results show that blacks were not excluded from the colono contracts on coffee plantations, nor from other manual occupations. However, they also provide evidence of other important forms of immigrant advantage and black disadvantage.

IMMIGRATION AND POPULATION CHANGE IN SÃO CARLOS

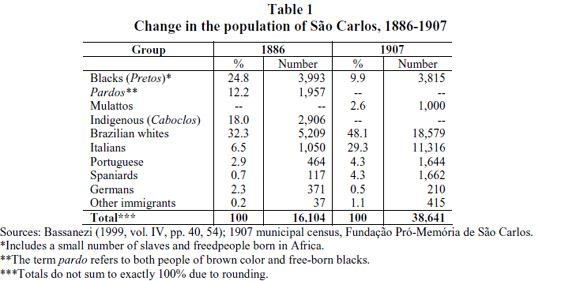

As a result of abolition, the expansion of coffee production and mass immigration, the São Carlos population grew rapidly and its composition changed dramatically. Table 1 compares local population data from the 1886 provincial census and the 1907 municipal census. Despite some alterations in racial categories, these data allow examination of change in relative proportions of whites and nonwhites, and demonstrate the growth of the various immigrant groups. In 1886, blacks, browns (pardos) and caboclos (descendents of indigenous people) constituted 55% of the total population of 16,104. Of the 5,950 blacks and browns in the municipality, 2,982 were enslaved and another 1,277 were ingênuos, the free children of enslaved mothers, who had to serve their masters until their twenty first birthday, in accordance with the 1871 Rio Branco law. In other words, 71.6% of blacks and browns in the municipality in 1886 were slaves or ingênuos. The proportion that had experienced captivity was even greater, because an unknown number of the others were libertos. The high proportion of slaves and children of slaves reflects the position of São Carlos at the time on the prosperous and expanding frontier of coffee production, where planters resisted liberating their slaves until the eve of abolition.

One cannot directly compare the "brown" (pardo) population of 1896 and the "mulatto" population of 1907. Although the "pardo" today refers to brown skin color, Hebe Mattos (1998) presents evidence that, in the nineteenth century, it also designated free born Afro-Brazilians of all colors. The use of the term "mulatto" instead of "pardo" in the 1907 municipal census suggests that, nineteen years after final abolition, the predominant racial categories referred primarily to skin color and other phenotypic characteristics. However, the contrast between ex-slaves and the freeborn still influenced these categories because there were more libertos and descendents among "blacks" and a greater proportion of people born free among "mulattos."2 The disappearance of the category caboclos (acculturated descendants of indigenous people) constitutes additional evidence that appearance, especially skin color, underlay the racial categories of 1907. Although some caboclos had probably left the municipality, going to regions further to the west, where they could still occupy land informally, many others must have been classified as mulattos, and some as whites or blacks. There were 2,051 foreigners in the municipality in 1886, half of them Italians.

By 1907, the proportion white in the local population had increased dramatically, due principally to immigration. From 1887 to 1902, São Carlos was one of the principal destinies of foreigners who passed through the immigrant hostel (Hospedaria dos Imigrantes) in the city of São Paulo, occupying first place in 1894 and second place in 1895 (Truzzi, 2000:58). In the two decades between these censuses, the number of Italians in Carlos increased tenfold and the number of other immigrants quadrupled, whereas the nonwhite population declined. The 15.247 foreigners enumerated in 1907 constituted approximately 40% of the total population, but this figure underestimates the immigrant presence because the children of foreigners born in Brazil were counted as Brazilians. In 1907, 67.1% of heads of families were immigrants and Italians headed half of the municipality's families. At that time, blacks and browns together constituted 12.5% of the total population of São Carlos, 14% of urban residents and 12% of rural residents.

OCCUPATIONS OF AFRO-BRAZILIANS, WHITE BRAZILIANS AND IMMIGRANTS

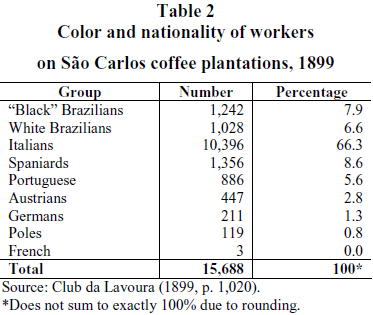

For some observers at the time, it was obvious that many libertos continued working on the plantations of western São Paulo. In the opinion of Cincinato Braga, a lawyer who wrote the introduction to the Almanach of São Carlos, published in 1894, "The Italian element predominates among agricultural workers, followed by the German, the Portuguese, the ex-slave, the caboclo, the Spanish and the Polish" (Augusto, 1894:li). Table 2 presents data collected in 1899 by the Clube da Lavoura (Agricultural Club) of São Carlos regarding the composition of the municipality's plantation labor force. The great majority of workers were immigrants: Italians constituted two thirds, and other foreigners contributed another fifth. However, those classified as "black Brazilians" were the third largest group, almost 8% of the workers, just behind the Spaniards.3

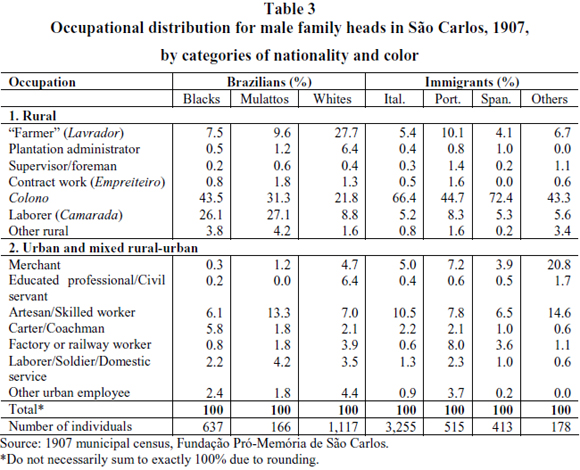

Table 3 presents the occupational distributions of male heads of families enumerated in the 1907 municipal census, separated by ethnic or racial group. The existing literature generally affirms that, in the new and rich coffee growing regions of western São Paulo, immigrants monopolized the family colono contracts, whereas blacks were only present on plantations as unskilled wage laborers (camaradas) or as specialized workers such as carters, masons or cowboys (Beiguelman, 1978:108; Dean, 1976:152; Holloway, 1980:173). As mentioned above, several authors claim that colonos on coffee plantations were often able to accumulate some capital, leading to certain degree of social mobility, due to the system of mixed remuneration, in the form of annual payments for the care of a certain number of coffee trees, payment for the quantity of coffee picked, free housing and, perhaps most important, the right to plant food crops for family consumption and sale. With years of work, good luck and good health, some families of colonos were able to save enough to buy small farms or shops (Stolcke, 1988:36-43).

As expected, Table 3 shows that immigrants, especially Italians and Spaniards, were particularly likely to be colonos, which is not surprising because the state government of São Paulo only paid the passage of agricultural families - or of those who claimed to be agriculturalists - and immigrants were only allowed to leave the immigrant hostel in the city of São Paulo after signing contracts with planters (Holloway, 1980:45-54). Among the Portuguese and "other immigrants", such as the Syrio-Lebanese or the Germans, there were many who had immigrated earlier, or had paid their own passage, which reduced the proportion with colono contracts.

The results also show, however, that blacks were not excluded from the colono contracts. Although Italian and, especially, Spanish families were more concentrated in this activity, it was also the most common occupational category for Afro-Brazilian heads of families. In 1907, 43.5% of families headed by a black male and 31.3% of those headed by a mulatto male were colonos. Summing blacks and mulattos, the 329 colono families headed by an Afro-Brazilian were more numerous than the 299 families of Spanish colonos or the 230 families of Portuguese colonos.

Consistent with the literature, the proportion of black and mulatto family heads who worked as rural laborers was much greater than that among immigrant family heads. Table 3 underestimates the number of European rural laborers, however, because it does not include single or unaccompanied men. Many southern Italians and Portuguese migrated to São Paulo alone, and many of them worked as plantation wage laborers. (Alvim, 1986; Leite, 1999; Serrão, 1982:119-127). Considering only men aged 15 to 60 who did not live in families, 30.9% of the 395 Italians and 45.7% of the 184 Portuguese counted in the 1907 census worked as rural wage laborers. These figures are not very different from those for black (41.9% of 296) and mulatto (45.1% de 51) men in the same age range who did not live in families.

Clearly, the idea that blacks were completely excluded from colono contracts is exaggerated. It is still possible, however, that racial discrimination by planters was stronger in the first few years after abolition. Large numbers of immigrants arrived in the first half of the 1890's, and the planters of western São Paulo who wanted to replace blacks with immigrants could easily do so. But in the second half of the decade the world price of coffee collapsed, followed by a fall in pay rates on São Paulo plantations and an increase in the number of immigrants who abandoned the plantations, moving to the cities or returning to Europe (Hall, 1969:143-147, 184-186; Holloway, 1980:177-180). As a result, planters had greater difficulty in finding workers during the final years of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth. In 1902, Italy prohibited subsidized immigration to Brazil, restricting even more the labor supply. Over time the prejudice of planters against immigrants, especially Italians, often seen as disorderly and violent, also grew (Andrews 1991:85-88; Monsma, 2008). In this context, it would make sense for planters to hire more Brazilians.

By 1907, São Carlos was no longer on the frontier of coffee production, and most coffee groves there were already mature; few families thus obtained empreiteiro contracts for clearing land or planting new coffee groves, which were potentially more lucrative (Bassanezi, 1974:136-137). However, black and mulatto family heads were more likely to hold these contracts than Italian family heads, probably because a much larger number of Italians were recent arrivals, with little coffee growing experience; among the Spanish, who only began arriving in large numbers at the beginning of the twentieth century, there were no empreiteiros in 1907.

Despite her focus on an older plantation region, Hebe Mattos (1998) provides clues about the possible social origens of the black colonos and empreiteiros in western São Paulo after abolition. This author emphasizes the struggle of nineteenth century slaves to form stable families, gain customary rights to land and maximize their autonomy within the system. All of this was more feasible for those who stayed in the same place for many years, especially if they never left their place of birth. The internal slave trade introduced a crucial distinction among slaves in the coffee producing regions of Southeastern Brazil: captives purchased from other regions, principally the Northeast, were separated from their families and communities of origin and had to recommence the struggle for autonomy, family formation, community ties and access to land. Plantations in western São Paulo were more recent, but Robert Slenes (1999) demonstrates that many slaves in this region were able to form families, living separately from the other slaves, and gained the right to cultivate plots of land. Although there is no systematic information on the origins of the black and mulatto colonos of São Carlos, the majority probably were born into the more established slave families or families of freeborn blacks, because planters preferred larger families for colono contracts and probably perceived those with extensive local kinship networks as more likely to remain in the area and continue working on the plantations. Other Afro-Brazilian colonos and empreiteiros undoubtedly had migrated from other regions, such as the Paraíba river valley, in search of better opportunities.4

A few blacks and mulattos occupied positions of authority on plantations in 1907. There were three black plantation administrators, two mulatto administrators, one black administrator's assistant and one mulatto foreman (feitor). Some of them were probably administrators of small plantations, but criminal trial records make clear that some Afro-Brazilians held positions of authority over white colonos and laborers. In 1895, the black administrator of a large plantation was supervising a group of Italian and Brazilian colonos engaged in road maintenance when he fought with the white administrator of a neighboring plantation.5

This census also provides evidence about the labor force on specific plantations. With a human population of almost a thousand, the Palmeiras plantation of João Augusto de Oliveira Salles was one of the largest in the municipality. Including female headed families, approximately 48% of the 162 families working on the plantation were headed by Italians, 19% by other immigrants, 17% by blacks, 7% by mulattos and 10% by white Brazilians. Among the immigrant families, 92% had colono contracts, whereas Brazilian families of all colors were distributed over a wider range of occupations. Eight (29%) of the 28 families headed by blacks, nine (56%) of the 16 headed by white Brazilians and only one of the 11 families headed by mulattos worked as colonos. Blacks headed two of the three empreiteiro families; an Italian headed the remaining one. Several of the Afro-Brazilians on this plantation were wage laborers, including eight black and five mulatto heads of families. Eight black and one mulatto heads of families were simply enumerated as "employees," a category which appears to identify principally those engaged in domestic service. Other black or mulatto family heads were specialized workers, including two carpenters, a cook, a saddlemaker, a jockey and an ant exterminator. The seven white Brazilian family heads who were not colonos included the administrator, two wage laborers, two artisans, and two others who apparently were tolerated settlers on plantation land (agregados).

The image changes little if we focus on individual workers instead of family heads. Examining only male workers between ages 12 and 65, the majority of the 50 blacks on the Palmeiras plantation was divided more or less equally among wage laborers (15), colonos (14) and "employee" (13); the majority of the 17 mulattos were wage laborers (7) or colonos (5); the great majority of the 169 immigrant workers were colonos; and over two thirds of the 67 white Brazilians were colonos, although some of them were laborers (7) or "employees" (4). The occupational distribution for women was similar to that for men, with the difference that there were larger proportions of laborers and specialized workers among women.

On the medium sized Santa Constança plantation, with 156 residents, the population composition was simpler, but still mixed immigrants and Afro-Brazilians: Italians headed twenty of the 28 families of workers, and there were no other immigrants; the other eight heads of families included four blacks, one mulatto and three white Brazilians. The administrator of Santa Constança was mulatto, but in other respects the occupational distribution by color and nationality was similar to that found on the Palmeiras plantation. The Jacaré plantation, with 150 residents, had only one black family, the colonos Pedro Clemente, 50, his wife Laura Helena, 40, and their nine children. The majority of the other 24 colono families was comprised of Italians, but there were also six colono families headed by white Brazilians and three headed by Portuguese.

Immigrants and Afro-Brazilians also met and competed in other manual occupations. Consistent with the existing literature, which affirms that ex-slaves preferred work that was not closely supervised, Table 3 shows that a high proportion of blacks worked in occupations allowing a certain degree of autonomy, such as the transport of cargo or people, but many Italians also worked in the same occupations. Relatively high proportions of mulattos and Italians were artisans or skilled workers. Immigrants did not enjoy any monopoly in the labor market and encountered Afro-Brazilians in almost all of the manual occupations.

The common affirmation that mass immigration resulted in the exclusion of Afro-Brazilians from the most desirable manual jobs is not confirmed by the 1907 São Carlos municipal census. Blacks and mulattos competed with immigrants in a wide variety of manual occupations, including those - such as colono or skilled work - which allowed some limited opportunities to accumulate capital. This does not mean, however, that mass immigration did no harm to Afro-Brazilians, for it produced a rapid increase in the number of poor people seeking employment, which limited the wages of all workers. The São Paulo state government's subsidized immigration program was a labor market intervention designed to weaken the negotiating power of workers. In the Paraíba river valley, with less immigrants, Afro-Brazilians could often negotiate better terms with planters, gaining relatively stable access to land (Rios, 2005). There is also abundant evidence of the prejudice of elites against blacks, especially libertos, and their preference for immigrants, at least in the first years after abolition. This analysis suggests that blacks and mulattos were able to compete with immigrants in spite of the racism of planters and other employers. To explain greater rates of subsequent social mobility among immigrants and their descendents, one must consider other forms of racial discrimination.

Considering the highest levels of the occupational distribution, it is clear that, with few exceptions, who were almost always mulattos, Afro-Brazilians were still excluded from the local elite almost two decades after final abolition. All of the great planters, those with properties larger than 500 São Paulo alqueires (1,210 hectares) listed in the Estatística Agrícola e Zootechnica of 1904-5 (Truzzi, 2004) and identified in the 1907 municipal census, were white. Almost all of the large-scale merchants, liberal professional and civil servants were also white. The 1907 census listed some blacks and mulattos as "merchants," but this category does not distinguish between great merchants, on the one hand, and small shopkeepers and street venders, on the other. No Afro-Brazilian exercised one of the learned professions - including here not only the liberal professions but also others that required primarily nonmanual work, such as teacher, accountant or priest - and the only black civil servant was a postal agent. There were, however, some large-scale immigrant coffee planters and many Italian, Portuguese and Syrio-Lebanese merchants, some of whom regularly paid for half or whole page advertisements in local newspapers. In fact, the number of Italians classified as merchants was three times greater than the number of Brazilian merchants. Even the Spanish, highly concentrated in the rural districts, had a consular agent in São Carlos.

The immigrant elite, comprised of planters, merchants and the owners of workshops and small factories, employed their compatriots, and probably were more biased in favor of immigrants than were Brazilian planters. The immigrant elite also defended the interests of poor immigrants. With the aid of richer or more educated countrymen, many immigrants sent complaints about the abuses of planters or the police to their consuls or vice-consuls in the city of São Paulo. The consuls would send the complaints on to the state police chief, asking for his help; the police chief then often asked for the intervention of the local police delegate, who sometimes resolved the problem.6 During the 1890's in São Carlos, the Italian merchant and journalist Giovanni Ferracciù, also known as Del Simoni, was an untiring defender of the Italian community. Although sometimes labeled an "anarchist" in the early years, with time he gained the respect of the local elite (Monsma, 2007).

There existed almost no Afro-Brazilian elite to employ and defend poor blacks and mulattos, and obviously there were no black consuls, all of which increased the vulnerability of poor people of African descent to the abuses of employers, the police and those who wanted to defraud or otherwise take advantage of them. For the majority of blacks and mulattos, the only possible defenders, in a country where the poor often needed the support of powerful patrons to resolve everyday problems, were to be found among the white Brazilian elite. The positions of the more fortunate blacks and mulattos in the patronage networks of powerful whites tended to maintain their subordination to whites and inhibit collective action by Afro-Brazilians in defense of their interests.

ACCESS TO PROPERTY

The category "farmer" (lavrador) used in the 1907 municipal census (see Table 3) seems to include all those involved in agriculture, from the great planters to informal occupants and tolerated settlers on the land of others (agregados); thus it does not serve to identify coffee planters. Among male family heads, approximately one in three blacks and one in ten mulattos was classified as a farmer, proportions much lower than those found among white Brazilians, but higher than those for Italians and Spaniards and a little lower than that for the Portuguese. On the other hand, only four (5.7%) of the 70 black or mulatto male family heads identified as "farmers" had land registered in the Estatística Agrícola e Zootéchnica of 1904-1905 (Truzzi, 2004) and, presumably, held official title to their land. Some could have bought land or regularized their titles during the interval between 1905 and the 1907 census, but the great majority of the other Afro-Brazilian "farmers" probably were landowners without official title, relatives of the owners, renters, sharecroppers, tolerated settlers or informal occupants of public or private lands. The percentages with land listed in the Estatística Agrícola were greater among the "farmers" of other groups: 29.5% of 356 white Brazilians, 16.1% of 186 Italians, 12.5% of 56 Portuguese e two of the seventeen Spaniards. All of these percentages are somewhat underestimated, due to the two year interval between data collection for the Estatística Agrícola and the local census, but underestimation is greater in the case of white Brazilians because the data exclude several cases of land possessed in common by the heirs of large-scale planters, who are not identified individually. The great majority of São Carlos properties owned by immigrants were smaller than 50 São Paulo alqueires (121 hectares), but some Italians, Portuguese, and one "Russian" had already become large coffee planters.

The Estatística Agrícola only includes three rural properties with owners identified as black farmers in the 1907 census. Bernardo Caetano had just one São Paulo alqueire (2.42 hectares) of "white" soil, half planted in vegetables and half used to graze four cows; he also had ten chickens. Elesbão Galo had ten alqueires of "sandy white" soil, used only as pasture for two cows and a mule. Finally, José Romão dos Reis had a relatively large property, 236 alqueires of "spotted" soil, but only two alqueires were planted with corn, rice and beans; over half the land was pasture for six steers, four cows and seven horses. None of these black proprietors planted coffee or employed immigrants.

On the other hand, the mulatto Francisco Antonio Borges was a fairly important planter, with 275 alqueires of white soil and 210,000 coffee trees, tended by 43 immigrants and 20 Brazilians. Linking the names of proprietors in the Estatística Agrícola to those of all family heads in the 1907 census reveals another mulatto planter, Argeo Vinhas, identified as a merchant in the census, who had 50 alqueires of white soil with 18,000 coffee trees tended by 24 immigrants. Vinhas had also served as third substitute police delegate for São Carlos in1902.7 In 1911, he would become one of the incorporators of the Companhia Industrial de S. Carlos, which established the Magdalena textile factory, and, in 1914, he would be one of the investors responsible for the introduction of electric streetcars in São Carlos (Camargo, 1915:lxi, lxvi-lxviii; Castro, 1916-17:41). These two successful mulattos were on their way to family whitening through marriage with whites, identified by Oracy Nogueira (1998:181-182), in his study of Itapetininga (São Paulo), as an important and perhaps obligatory step for the upward social mobility of Afro-Brazilians in the first half of the twentieth century. Vinhas had married an Italian and did not yet have children in 1907. Francisco Borges married a white Brazilian, with whom he had seven children by 1907, all listed as whites in the municipal census.

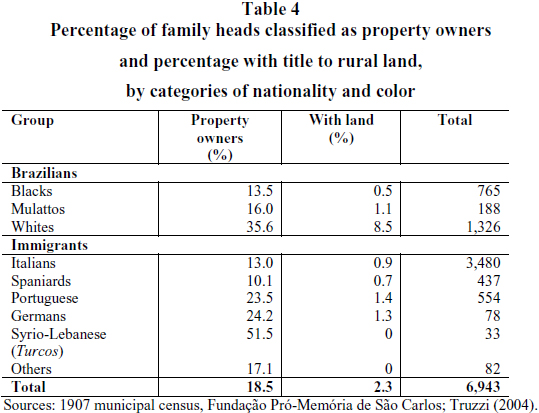

The 1907 São Carlos census also includes a variable indicating if the individual was a property owner. It is not possible to know the definition of property used here, because the instructions for the census takers were lost, but the variable seems to refer to real estate ownership because the number of "proprietors" is much greater than the number of landowners listed in the Estatística Agrícola, and many urban residents are considered property owners. Table 4 includes the percentage of each ethnic or racial group listed as property owners in this census. The earlier immigrant groups (Portuguese and Germans) and those highly concentrated in commercial activity (Syrio-Lebanese) had a higher probability than other immigrants of acquiring property, but only the Syrio-Lebanese had a higher percentage of property owners than the white Brazilians. Italians and Spaniards, most of whom were colonos on the coffee plantations, had proportions of proprietors lower than that found among blacks. The second column of Table 4 shows the percentage of family heads in each group with rural land listed in the Estatística Agrícola of 1904-5. Less than 1% of Italians and Spaniards had land registered in this agrarian census. In both groups, the percentage of landowners was greater than the 0.5% found among blacks, but a little less than the percentage among mulattos, and much less than the 8.5% among white Brazilians.

The relatively low proportions of property owners among Italians and Spaniards could simply reflect the fact that many families of these nationalities were recent arrivals in Brazil and thus had not lived in the country long enough to save money and buy properties. For immigrants with some children born in Europe and some in Brazil, it is possible to estimate the number of years in Brazil by the mean, plus 0.5, of the ages of the last child born in the country of origin and the first born in Brazil. It is also reasonable to assume that the great majority of the foreigners whose children were all born in Brazil had been present in the country for a period equal to or greater than the age of the first-born child. Using these two strategies, it was possible to identify 1,348 Italian and 97 Spanish family heads presumably present in Brazil for ten years or more. In this subsample, 15.8% of Italians and 21.6% of Spaniards were property owners, and 1.2% of Italians and 2.1% of Spaniards had land listed in the Estatística Agrícola. Clearly the chances of property acquisition by immigrants increased with time in Brazil, but if we consider only Afro-Brazilians with children aged ten or more - to avoid comparing immigrants present in the country for a decade or more with a clearly younger group of blacks and mulattos - the percentage with property among the 337 blacks changes little, but rises to 22.7% among the 75 mulattos, and the percentage with rural land titles rises to 1.2% among blacks and 1.3% among mulattos. In other words, even among Italian and Spanish family heads present in Brazil ten years or more, the proportion of rural landowners continues quite low. In the case of Italians, this proportion is equal to that found among blacks of roughly the same age.

These data provide little evidence that immigrant groups employed mainly as colonos on coffee plantations enjoyed significant advantages over Afro-Brazilians in the aquisition of land or other property in the first decades after abolition. On the other hand, immigrants long established in the region, such as many of the Germans and Portuguese, as well as groups highly involved in commercial activity, such as the Syrio-Lebanese and the Portuguese, did have greater chances of acquiring property. It is also probable that many of the Italians and Spanish who bought land or urban properties were merchants or artisans who had never been colonos. In subsequent decades, with coffee crises and declining productivity of the aging coffee groves in west-central São Paulo, many plantations of the region would be divided and sold to immigrants or their children (Durhan, 1966:19-26; Holloway, 1980:144-166). Thus it is still possible that research on this later period will find evidence of immigrant advantage over Afro-Brazilians with respect to the chances of acquiring land.

FAMILY STRUCTURE

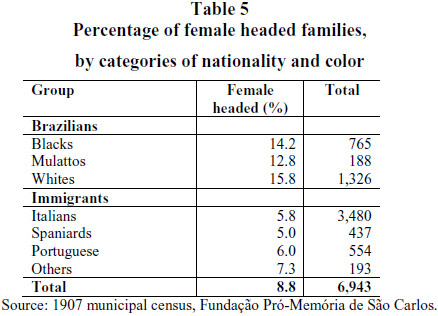

Florestan Fernandes (1978) proposed the thesis, much criticized today, that the disadvantage of libertos stemmed partly from their "anomie." One way to address this issue with data from the 1907 São Carlos census is to examine the family structure of the various groups, under the assumption that, in a traditional catholic context, a high proportion of female headed households indicates the "anomie" of men, who abandon their families or refuse to recognize their children conceived out of wedlock. Table 5 shows that all of the principal immigrant groups had low proportions of female headed families, probably because the subsidized immigration policy of São Paulo favored families headed by men. Among black and mulatto family heads, the percentages female were a little lower than the 15.8% found among white Brazilians. These results do not support the idea that Afro-Brazilian family life tended to be unstable.

Another manifestation of "anomie" in a traditional catholic context would be low rates of marriage. But marriage rates for blacks and mulattos were higher than those for white Brazilians. Among those aged 21 or more, 86.6% of black women and 89.1% of mulatto women had married (including widows) or lived in a stable union - conditions generally indistinguishable in this census, whereas the equivalent figure for white Brazilian women was 83.9%. Among men, 77.7% of blacks, 75.6% of mulattos and 68.9% of white Brazilians had married or lived in stable unions. Once again, the results are not consistent with the idea of greater "anomie" among Afro-Brazilians. In fact, there was a wave of marriages of libertos throughout the São Paulo interior in the first few months after abolition, suggesting that many slaves had wanted to marry, but had been impeded by their masters.8

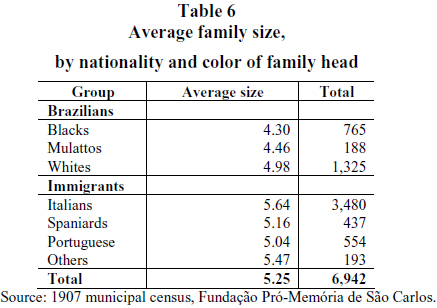

Family size could also influence possibilities for saving money and acquiring property. Among colonos, especially, larger families could tend more coffee trees and earn more. Because immigration policy favored families and planters preferred larger families for colono contracts (Stolcke, 1988:17), immigrant families in the coffee producing regions were probably larger, on average, than Brazilian families. Italian culture, especially that of northern Italian peasants, also encouraged joint families, in which married brothers and their families lived and worked together, often under the supervision of their father (Alvim 1986:30; Durhan 1966:30; Kertzer e Brettell 1987; Pereira 2002:185-189). It was relatively common for Italian couples to emigrate along with brothers, in-laws and fathers, as well as their own children, a tendency which increased the number of workers per family.

Table 6 presents average family size among the principal ethnic and racial groups, including as family members not only parents and children but also others living with the family. Immigrant families tended to be larger, although there is little difference between average Portuguese family size and that for white Brazilians. Italians had the largest average family size, 5.6, whereas families headed by blacks and mulattos were the smallest, with average sizes of 4.3 and 4.5, respectively.9 Table 6 includes both female and male headed families, but even when we include only male headed families the relative positions of the different groups are unchanged and the distances between them remain more or less the same. Thus the larger proportion of female headed families among Brazilians cannot explain these differences in family size. The larger size of Italian families presumably resulted partly from a larger number of children and partly from the presence of parents, siblings, in-laws and other relatives. Unfortunately this census does not always clearly indicate family relations, so it is not always possible to distinguish between children and other relatives.

The observed racial differences in the number of children could reflect differences in the average age at marriage for women, if Afro-Brazilian women tended to marry later than white women. One can estimate the percentage of women that marry for the first time at each age with the increment in percentage ever married (including widows). These estimates can then be used as weights to estimate the average age at marriage. Among women marrying between ages 14 and 25 - at ages over 25, the proportion of women ever married continues relatively stable - the estimated average age at marriage for Afro-Brazilian women is 19.03, whereas that estimated for white Brazilian women is 19.26 and that for Italian women is 19.62. Despite marrying earlier, black and mulatto women apparently had less children than white women at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Racial differences in mortality rates, especially infant and child mortality and the mortality of women during childbirth, could explain much of the racial difference in family size among Brazilians. 1907 municipal census data allow some inferences regarding the mortality of mothers. Consistent with the hypothesis of greater black mortality during childbirth, the percentage of widowers among black men who had ever married, 10.3%, is about 40% greater than the 7,3% observed among white Brazilian men, whereas the percentage of widows among ever married black women, 20.3%, is only 7% greater than the 18.9% among white Brazilian women. (Proportions of widows and widowers among immigrants are lower and are not comparable to those among Brazilians because the subsidized immigration program favored families with both parents present.) On the other hand, the percentage of mulatto widowers, 4.9%, is lower than that among Brazilian whites. Consistent with the somewhat better position of mulattos in the occupational structure, it appears that the wives of mulatto men enjoyed better health conditions and better access to medical services than the wives of black men.

The lack of medical services would also have increased the infant and child mortality rates of blacks. In addition, the urban and suburban neighborhoods where the black population concentrated were probably less healthy, influencing especially the chances of infant and child survival. After abolition, many libertos settled on the urban periphery of São Carlos, in the Santa Izabel and Vila Pureza neighborhoods (Devescovi, 1987:57; Truzzi 2000:52). After 1890, many urban residents had access to canalized spring water, distributed at four public fountains, but this improvement did not reach the urban periphery (Augusto 1894:75; Camargo 1915:xxx), where streams were undoubtedly polluted by sewage, increasing infant and child mortality rates.

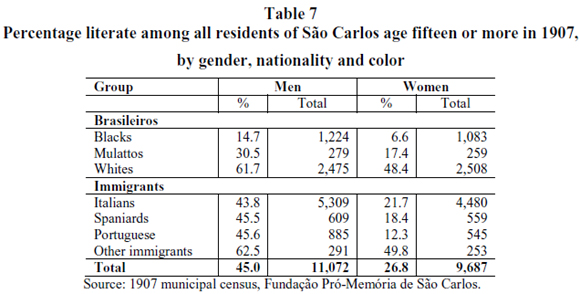

LITERACY

It is also likely that Afro-Brazilians, especially libertos, suffered important disadvantages in access to formal education. The 1907 municipal census includes information on literacy, which, in addition to qualifying people for better jobs, indicates basic schooling and better access to information. Table 7 presents percentages literate for the various ethnic and racial groups, among those aged 15 or more. Black literacy rates were much lower than those in any other group: 14.7% of black men and only 6.6% of black women could read, less than half of the percentages among mulattos, who had the second largest proportion of illiterate men and the third largest proportion of illiterate women. The principal immigrant groups had literacy rates lower than those for white Brazilians but much higher than those of blacks. The probability of being literate is about three times greater for an Italian, Spanish or Portuguese man than it is for a black man. In all groups, female literacy rates are much lower than male rates. Among blacks, Italians, Spanish and Portuguese, the percentages of literate women is less than half that for men. Even so, Italian and Spanish women are about three times more likely than black women to be literate. Portuguese women are a particularly illiterate category, with only 12.3% literate, which is less than the percentages literate among mulatto women or black men, but still almost double the literacy rate among black women.

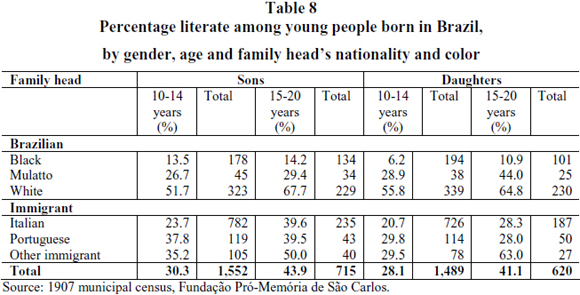

With the exception of those who arrived in Brazil as children, literacy rates of immigrants say more about education in the country of origin than in Brazil. To evaluate Brazilian educational opportunities available to the different groups, it is important to compare the children of Brazilians with the Brazilian children of immigrants. Table 8 presents the percentage literate among young people born in Brazil who were living with their parents at the time of the 1907 municipal census, separated by gender and age categories, and by ethnic and racial category of the family head. According to the São Paulo state educational reform of 1892, school attendance was obligatory for children between ages seven and twelve (Marcílio, 2005:138-139). Table 8 includes children aged ten or more because those who began school at age seven would have studied for two to three years by their tenth birthday, enough time to learn to read.

This table shows considerable progress toward the elimination of gender differences in literacy among the younger generation although there were still significant gender differences among blacks, Italians and Portuguese. The educational disadvantage of blacks continues, however, with literacy rates for both genders much lower than those of any other group. In 1905, a large public school opened in downtown São Carlos, with 346 alunos (Castro, 1916-17:110-111). There were also fifteen smaller public schools scattered throughout the municipality, six of them municipal and nine of them state schools, with a total of about 620 students, as well as several private schools (Augusto, 1905:47-53; Almeida, 2006:31-32; Truzzi, Nunes and Tilkian, 2008:148-149). But it appears that black children had limited access to schools. Although the number of children of mulattos was relatively small, the results suggest that their situation was better, with literacy rates of sons in both age categories roughly double those among sons of blacks. Daughters of mulattos had literacy rates about four times higher than those for daughters of blacks.

The Brazilian born children of Italians, especially sons, manifest a tendency for late learning, which is consistent with the assertion in the immigration literature that many colonos valued savings more than the education of their children, sending them to work in the coffee groves rather than to school. On the other hand, in the 15 to 20 age category, percentages literate among sons and daughters of Italians are equal to those for the children of Portuguese and, in the case of sons, considerably higher than those for the sons of blacks and mulattos. In 1907, the Sociedade "Dante Alighieri" of São Carlos already maintained Italian schools in the city for both sexes (Augusto, 1905:49; Truzzi, Nunes and Tilkian, 2008:148). There is no evidence of a school specifically for Afro-Brazilians in the municipality at this time. The Almanach de S. Carlos para 1915 mentions a school maintained by the Sociedade Beneficente Luiz Gama, which presumably served primarily the black and mulatto community (Camargo, 1915:153-154), but it appears that this school did not last long, for the Almanach-Album of 1916-17 does not mention it (Castro, 1916-17).

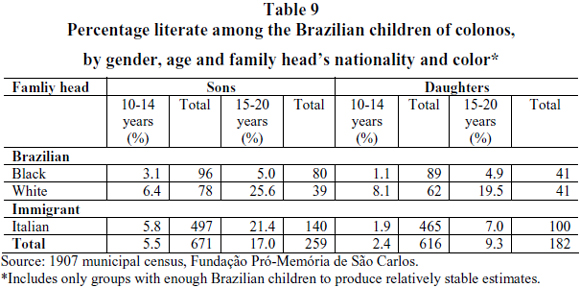

The great majority of Italians still lived in the countryside in 1907, and could not send their children to urban Italian schools. Table 9 compares the percentages literate among Brazilian born children of Italian and Brazilian colonos, both black and white - other colono groups are excluded here because they were present in small numbers or had not been in Brazil long enough to have many Brazilian born children.10 Literacy rates were low in all three groups, reflecting the importance of family labor in the coffee groves and the long distances that many children of colonos had to walk to reach the nearest school. But even among colonos, literacy rates were lower for children of blacks. In the 15 to 20 age category, the percentage literate among sons of Italian colonos was four times that among the sons of black colonos. In both age groups, the literacy rate for sons of Italians is relatively close to that for the sons of white Brazilian colonos. On the other hand, literacy rates for daughters of Italian colonos are closer to, but still higher than, those for daughters of black colonos. It seems that Italian colonos prioritized the schooling of sons over that of daughters. In both age categories, the sons of Italian colonos were about three times more likely to be literate than their daughters.

Why were the literacy rates of young blacks so low? Undoubtedly, many private schools simply turned away black students, even when parents could afford their fees. With respect to public schools, which were the ones that really mattered for the literacy of the poor, there was no legal restriction on the attendance of black children, which was officially mandatory. The difference in literacy rates between Brazilian born children of immigrants and blacks cannot be a consequence of black child labor because children of all poor ethnic and racial groups worked, especially the children of colonos.

Research on how children learn to read has shown that those exposed to the written word in the home before they begin schooling learn more easily than others (Baker, Scher and Mackler, 1997; Sonnenschein and Munsterman, 2002). Thus the children of illiterates face greater frustration in learning to read and may stop attending school where it is not effectively obligatory. In part, the illiteracy of black children in early twentieth century Brazil may have simply reproduced the illiteracy of their parents, which in turn was largely a consequence of slavery. But this tendency can only explain part of the racial difference, because most immigrant parents were also illiterate and the poor whites who were more or less literate generally read little and had very little written material at home. Even when we examine the proportions literate among children of illiterate parents, the racial differences continue. For example, among sons and daughters of illiterate blacks, the percentages literate in the 15 to 20 age category are 9.0% (of 122) and 6.5% (of 93), respectively, whereas the equivalent percentages for the sons and daughters of illiterate Italians are 23.6% (of 123) and 11.8% (of 102).

It is important to consider other possible causes of the extremely low literacy rates among black children and adolescents. First, the teachers, almost all of them white, probably believed that black children were less intelligent, when they were not overtly hostile to them. Recent research in the USA has shown that lower expectations of teachers with regard to black students translate into more limited performance by these students (Clifton et al., 1986; McKown and Weinstein, 2008). As Brazilian stereotypes of blacks were more openly pejorative at the beginning of the twentieth century than today (Schwarcz, 1987), the low expectations of teachers must have strongly discouraged the efforts of black children to learn.

In the schools, black children and adolescents could face another form of racism, the physical and symbolic violence of their peers, behavior often referred to today with the term "bullying." In the first decades after abolition, there was much violence between blacks and immigrants in western São Paulo, and in these incidents immigrants often manifested clearly racist attitudes (Monsma, 2006). The children of immigrants tended to internalize the same disdain for blacks, perhaps in less disguised forms. For example, after arguing with a black man over 90 years old in a rural tavern in 1915, a fifteen year old Brazilian, son of Italians, bought two boxes of cartridges and left on horseback with a twenty year old Italian friend to meet the elderly black man on the road where, without further ado, they killed him with four pistol shots.11 The attitudes of teachers and mistreatment by white children - the great majority - must have discouraged many black children from attending school and led others to abandon their studies.

In 1907, the elite private schools of São Carlos were still reserved almost exclusively for white Brazilians. In 1905, French nuns from the Congregation of the Holy Sacrament established the Colégio São Carlos, a school for girls which in 1907 functioned in the former mansion of the Conde de Pinhal (Camargo, 1915:23-54; Truzzi, Nunes e Tilkian, 2008:149). The 1907 census lists 34 students from rural areas of the municipality who boarded at the new school. All were white and almost all had Portuguese surnames, including those of several of the great São Carlos coffee planters, such as Arruda, Botelho, Sampaio e Salles.

A few years later, the Escola Normal Secundária de São Carlos would become another preserve of the elite and the middle class. This state academy for advanced teacher training was the only institution of its kind in the interior of São Paulo when it was inaugurated in 1911 (Nosella and Buffa, 2002; Truzzi, Nunes and Tilkian, 2008:154-60). According to Nosella and Buffa (2002), who researched the school's records and interviewed former students, the daughters of Brazilian planters and merchants predominated among the first classes admitted. There were many fewer male students, and they tended to come from less wealthy families. But in the first graduating class, of 1914, comprised of seven male and 27 female students, there were already one female student with a German surname and three with Italian surnames (Camargo, 1915:lxv). Over time, according to Nosella and Buffa (ibidem), more daughters and sons of immigrants appeared among the students and, especially after the crisis of the 1930's, the school became less elitist, less oriented to the formation of the cultural dowry of future wives of the elite and more oriented to professional training for teaching. Despite this, in photos published by these authors of several classes at the Escola Normal and the Model School attached to it, portraying a total of 288 students in the period from 1911 to 1933, only three possibly black students can be identified.

CONCLUSIONS

Evidence from the 1907 São Carlos municipal census provides little support for the thesis, widely diffused in the relevant literature, that much of the long-term advantage of immigrants and descendants in relation to Afro-Brazilians was due to exclusion of blacks and mulattos from colono contracts on coffee plantations and other forms of manual employment. In addition to manual work of all kinds on plantations, blacks and mulattos competed with immigrants in a wide variety of urban occupations. Italian and Spanish families were highly concentrated on plantations as colonos because planters contracted colonos in family units, the São Paulo subsidized immigration program favored peasant families and those who arrived under this program were sent to the plantations. Afro-Brazilians were never totally excluded from colono contracts, however, and in 1907 colono was the most common occupation of both black and mulatto male heads of households. This should not be surprising. For planters, that was the place of blacks, working in the fields and serving them. What was much less acceptable to white Brazilian elites was any Afro-Brazilian pretension to social mobility and equality with them.

It is still possible that planter discrimination against Afro-Brazilians, especially libertos, was greater in the first years after abolition, when salaries were higher and there was a greater supply of immigrant workers. In any case, if planters preferred immigrants as colonos, two decades after abolition this preference still had not translated into large advantages for immigrants with respect to acquisition of land or other real estate. However, the simple presence of large numbers of poor European workers depressed wages, harming blacks and other Brazilian workers.

This article identifies three areas in which Afro-Brazilians, especially blacks, suffered clear disadvantages in comparison to immigrants. First, there was almost no Afro-Brazilian elite, whereas there were many immigrant merchants and professionals, and some large-scale immigrant coffee planters. It was in part due to the presence of an educated immigrant elite of merchants, journalists, doctors, teachers and priests, especially among Italians, that immigrants could fight the abuses of planters and the police, and struggle to revert negative stereotypes of immigrants that circulated among Brazilians (Monsma, 2007). The immigrant elite also provided employment in plantations, workshops and stores, and could help poor and illiterate compatriots resolve bureaucratic problems. Blacks and mulattos generally could only gain such benefits through the patronage of white Brazilian elites, which inhibited their collective organization.

There were a few successful mulattos, but they apparently were engaged in "whitening" themselves and their children, and did not identify with poor blacks. In fact, much of the evidence discussed above suggests that the position of mulattos in 1907 was better than that of blacks. This was not only a matter of greater discrimination against those who were darker. A much greater proportion of the mulattos had probably been born free in the time of slavery, whereas the majority of São Carlos blacks were libertos or children of libertos. In other words, the stigma of slavery and negative consequences of captivity - such as lack of schooling or, in the case of many northeasterners who had been sold to São Paulo planters, the lack of extended families in São Carlos - were concentrated among blacks.12

Second, immigrant families were larger, on average, than Brazilian families, and Afro-Brazilian families were the smallest among the groups studied here, despite the fact that black and mulatto women tended to marry earlier. Larger families were preferred by planters and could earn more as colonos or contractors on plantations. In addition to the fact that the subsidized immigration program favored large families, two factors probably influenced these differences in family size. First, many Italians arrived in complex families, including other relatives in addition to the nuclear family. Second, it seems that blacks suffered higher mortality rates than other groups, especially white Brazilians, as a result of worse sanitation in the neighborhoods where they concentrated and racial discrimination in medical care.

Third, the literacy rate for among Afro-Brazilians, especially blacks, was very low compared to those of both immigrants and white Brazilians. Almost two decades after final abolition, the Brazilian Republic was still doing little to educate blacks. At the time, illiterates did not suffer great disadvantages in the manual labor market, but were excluded from many of the better jobs, especially in commerce or public service. In addition to this, the high percentages of black and mulatto illiterates left the great majority of them vulnerable to expropriation or fraud. For example, it is quite likely that many of the black and mulatto "farmers" listed in the census had bought land but never regularized the titles. Many other black or mulatto "proprietors" of urban houses had undoubtedly never gained official recognition of their property rights. If the entangled Brazilian bureaucracy still creates problems for the educated middle class today, and many of the poor simply give up on regularizing their properties, it is easy to imagine that many, if not the majority, of libertos and their children passed their entire lives in informal pursuits, without identity documents, employment contracts or property titles.

Other important forms of racial discrimination cannot be addressed with the data analyzed here, but they also merit the attention of researchers. One is the social rejection of blacks by Brazilian elites. As a consequence of this, upwardly mobile immigrants and their descendants were more easily accepted by local elites than Afro-Brazilians with the same levels of education and wealth. Studying another small city in São Paulo state, Oracy Nogueira (1998:181-182) observed that, in the first half of the twentieth century, black upward mobility was almost always accompanied by a process of whitening through marriage with whites, either Brazilian or immigrant, and the loss of Afro-Brazilian identity, which was apparently necessary for acceptance by the local elite. "As a consequence, every conquest by a black or mulatto who is able to prevail economically, professionally or intellectually tends to be absorbed in one or two generations by the white group" (Nogueira, 1998:182). Many immigrants engaged in upward social mobility also married white Brazilians, which probably facilitated acceptance by local elites, but upwardly mobile immigrant families could also win elite approval without marrying into Brazilian families and without rejecting their origins and changing their ethnic identities.

It is also important to investigate later discrimination against blacks and mulattos in the labor market by immigrants and descendants, who controlled an increasing number of jobs, favored those of similar origins, and rapidly internalized racism. In addition, the presence of immigrants and descendants in the schools continued to increase after the time of the census examined here, including not only the majority of students but also increasing numbers of teachers, which exposed black and mulatto children to various forms of discrimination and humiliation in everyday school life. Despite being recent arrivals, immigrants soon became "established" groups in relation to Afro-Brazilians, whom they relegated to the position of "outsiders," in the terms of Elias (1994), for whom the established are groups with greater organization and social cohesion, allowing them to exclude outsiders from positions of power and stigmatize them as morally inferior. The greater organization and power of immigrants was partly a consequence of their superior numbers, but it also resulted from the existence of a social elite in each immigrant group. In the absence of an Afro-Brazilian elite, blacks and mulattos remained relatively disorganized and found it difficult to combat the racial stereotypes fabricated and reproduced by whites, including immigrants and their descendants.

It is not possible to extract direct implications for contemporary public policy from this study of the post-abolition period because the past hundred years have seen many important changes in the nature of racism and racial inequalities. It is notable, however, that two of the Afro-Brazilian disadvantages that appear with greatest force in this research - exclusion from the elite and educational barriers - are still at stake today in debates about affirmative action.

NOTES

1. The original census list is deposited in the Fundação Pró-Memória de São Carlos (hereinafter FPM).

2. As a result of tendencies for masters to freed their children as well as miscegenation between free blacks and whites.

3. The Clube da Lavoura did not include any color category between white and black. The great majority of mulattos were presumably classified as "blacks."

4. On internal migration and the employment of Brazilian colonos in the last years of slavery, cf. Moura (1998:153-182).

5. FPM, Processos Criminais, Caixa 257, nº 25, Alberto José de Castro, 1895.

6. Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo (AESP), Polícia, several latas, 1894-1902.

7. FPM, Censo Municipal de 1907, vol. 7, p. 12; FPM, Criminais, C. 462, N. 2.635, 1902; Argeo Vinhas to Chefe de Polícia, São Carlos, 04/11/1902, AESP, Polícia, CO3003.

8. Police delegates complained about the large gatherings of blacks that formed for marriage celebrations. The subdelegate of Santa Cruz da Conceição wrote to the state police chief: "It is customary here for marriages of libertos to happen on Saturdays; and on these occasions, a large number of blacks gather in the parish center and commit many disturbances" (08/10/1888, AESP, Polícia, CO2693).

9. Average Italian family size was also much larger than that for other groups on the Santa Gertrudes plantation, in Rio Claro (Bassanezi, 1974:126).

10. Spanish and Portuguese colonos only began arriving in large numbers in the first years of the twentieth century and still did not have many Brazilian born children in 1907.

11. FPM, Processos Criminais, Caixa 268, nº 7.723.

12. Whatever the validity of grouping blacks and mixed race people (pardos) in the same category (negros) for research on racial inequality today, this procedure clearly is not justified for the first decades after abolition and only hides the degree of racism suffered by those socially classified as blacks.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

. Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo

Polícia

. Fundação Pró-Memória de São Carlos

Censo Municipal de 1907

Processos Criminais

ALMEIDA, Maria Salette Ramalho de. (2006), Aspectos da Instrução Pública em São Carlos na Segunda Metade do Século XIX. São Carlos, RiMa.

ALVIM, Zuleika M. F. (1986), Brava Gente! Os Italianos em São Paulo, 1870-1920. São Paulo, Editora Brasiliense.

ANDREWS, George Reid. (1991), Blacks and Whites in São Paulo, Brazil, 1888-1988. Madison, University of Wisconsin Press.

AUGUSTO, Joaquim. (1894), Almanach de 1894. São Carlos, O Popular.

AZEVEDO, Célia Maria Marinho de. (1987), Onda Negra Medo Branco: O Negro no Imaginário das Elites. Século XIX. Rio de Janeiro, Paz e Terra.

BAKER, Linda; SCHER, Deborah e MACKLER, Kirsten. (1997), "Home and Family Influences on Motivations for Reading". Educational Psychologist, vol. 32, no 2, pp. 69-82.

BASSANEZI, Maria Silvia Casagrande Beozzo. (1974), As Relações de Trabalho em uma Propriedade Rural Paulista, 1895-1930. Tese de Doutorado em História, Rio Claro (SP), Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Rio Claro.

______. (org.). (1999), São Paulo do Passado, vol. IV, Dados Demográficos 1886. Campinas, NEPO/Unicamp.

BEIGUELMAN, Paula. (1978), A Formação do Povo no Complexo Cafeeiro: Aspectos Políticos. 2ª ed. São Paulo, Livraria Pioneira.

CAMARGO, Sebastião (org.). (1915), Almanach de S. Carlos para 1915. São Carlos, Typ. Joaquim Augusto.

CASTRO, Franklin de (org.). (1916-17), Almanach-Album de São Carlos, 1916-1917. São Carlos, Typographia Artística.

CLIFTON, Rodney A. et al. (1986), "Effects of Ethnicity and Sex on Teachers' Expectations of Junior High School Students". Sociology of Education, vol. 59, no 1, pp. 58-67.

CLUB DA LAVOURA. (1940), "Estatistica Agricola do Municipio de S. Carlos do Pinhal organisada pelo Club da Lavoura, 1899". Revista do Instituto do Café do Estado de São Paulo, vol. 15, no 161, pp. 1.017-1.028.

COSTA, Emília Viotti da. (1999), Da Monarquia à República: Momentos Decisivos, 7ª ed. São Paulo, UNESP.

DEAN, Warren. (1976), Rio Claro: A Brazilian Plantation System, 1820-1920. Stanford, Stanford University Press.

DEVESCOVI, Regina C. Balieiro. (1987), Urbanização e Acumulação: Um Estudo sobre a Cidade de São Carlos. São Carlos (SP), Arquivo de História Contemporânea, Universidade Federal de São Carlos - UFSCar.

DURHAN, Eunice Ribeiro. (1966), Assimilação e Mobilidade: A História do Imigrante Italiano num Município Paulista. São Paulo, Universidade de São Paulo.

ELIAS, Norbert. (1994), "Introduction: A Theoretical Essay on Established and Outsider Relations", in Elias, Norbert e Scotson, John L., The Established and the Outsiders: A Sociological Enquiry into Community Problems. 2ª ed. Londres, Sage.

FERNANDES, Florestan. (1978), A Integração do Negro na Sociedade de Classes, vol. 1, O Legado da "Raça Branca". 3a ed. São Paulo, Ática.

HALL, Michael McDonald. (1969), The Origins of Mass Immigration in Brazil, 1871-1914. Tese de Doutorado em História, Nova York, Columbia University.

HASENBALG, Carlos Alfredo. (1979), Discriminação e Desigualdades Raciais no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Edições Graal.

HOLLOWAY, Thomas H. (1980), Immigrants on the Land: Coffee and Society in São Paulo, 1886-1934. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press.

KERTZER, David I. e BRETTELL, Caroline. (1987), "Advances in Italian and Iberian Family History". Journal of Family History, vol. 12, no 1-3, pp. 87-120.

LEITE, Joaquim da Costa. (1999), "O Brasil e a Emigração Portuguesa (1855-1914)", in Fausto, Boris (org.), Fazer a América: A Imigração em Massa para a América Latina. São Paulo, EDUSP.

MACHADO, Maria Helena Pereira Toledo. (1987), Crime e Escravidão: Trabalho, Luta e Resistência nas Lavouras Paulistas, 1830-1888. São Paulo, Editora Brasiliense.

______. (1994), O Plano e o Pânico: Os Movimentos Sociais na Década da Abolição. Rio de Janeiro/São Paulo, Editora UFRJ/ EDUSP.

MACIEL, Cleber da Silva. (1997), Discriminações Raciais: Negros em Campinas (1888-1926). 2ª ed. Campinas, Centro da Memória-Unicamp.

MARCÍLIO, Maria Luiza. (2005), História da Escola em São Paulo e no Brasil. São Paulo, Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo e Instituto Fernand Braudel.

MATTOS, Hebe Maria. (1998), Das Cores do Silêncio: Os Significados da Liberdade no Sudeste Escravista - Brasil, século XIX. Rio de Janeiro, Nova Fronteira.

MCKOWN, Clark e WEINSTEIN, Rhona S. (2008), "Teacher Expectations, Classroom Context, and the Achievement Gap". Journal of School Psychology, vol. 46, pp. 235-261.

MONSMA, Karl. (2005), "Desrespeito e violência: fazendeiros de café e trabalhadores negros no Oeste paulista, 1887-1914". Anos 90, vol. 12, no 21/22, pp. 103-149.

. (2006), "Symbolic Conflicts, Deadly Consequences: Fights between Italians and Blacks in Western São Paulo, 1888-1914". Journal of Social History, vol. 39, no 4, pp. 1123-52.

. (2007), "Emergência e Declínio do Perigo Imigrante' no Interior Paulista, 1880-1900". Trabalho apresentado no 31o Encontro Anual da ANPOCS, Caxambu, MG.

. (2008), "A Polícia e as Populações Perigosas' no Interior Paulista, 1880-1900: Escravos, Libertos, Portugueses e Italianos", in Desigualdade na Diversidade: 26ª Reunião Brasileira de Antropologia (CD ROM). Brasília, Associação Brasileira de Antropologia.

MOURA, Denise A. Soares de. (1998), Saindo das Sombras: Homens Livres no Declínio do Escravismo. Campinas, Centro de Memória-Unicamp.

NOGUEIRA, Oracy. (1998), Preconceito de Marca: As Relações Raciais em Itapetininga. São Paulo: Edusp.

NOSELLA, Paolo e BUFFA, Ester. (2002), Schola Mater: A Antiga Escola Normal de São Carlos, 1911-1933. São Carlos, EdUFSCar.

PEREIRA, João Baptista Borges. (2002), Italianos no Mundo Rural Paulista. São Paulo, EDUSP.

RIOS, Ana Lugão. (2005), "Filhos e Netos da Última Geração de Escravos e as Diferentes Trajetórias do Campesinato Negro", in Rios, Ana Lugão e Mattos, Hebe. Memórias do Cativeiro: Família, Trabalho e Cidadania no Pós-Abolição. Rio de Janeiro, Civilização Brasileira, pp. 191-230.

RIOS, Ana Maria e MATTOS, Hebe Maria. (2004), "O Pós-Abolição como Problema Histórico: Balanços e Perspectivas". Topoi: Revista de História, vol. 5, no 8, pp. 170-98.

SANTOS, Carlos José Ferreira dos. (1998), Nem Tudo Era Italiano: São Paulo e Pobreza (1890-1915). São Paulo, Annablume.

SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz. (1987), Retrato em Branco e Negro: Jornais, Escravos e Cidadãos em São Paulo no Final do século XIX. São Paulo, Companhia das Letras.

SERRÃO, Joel. (1982), A Emigração Portuguesa: Sondagem Histórica. 4ª ed. Lisboa, Livros Horizonte.

SLENES, Robert W. (1999), Na Senzala, uma Flor: Esperanças e Recordações na Formação da Família Escrava - Brasil Sudeste, Século XIX. Rio de Janeiro, Nova Fronteira.

SONNENSCHEIN, Susan e MUNSTERMAN, Kimberly. (2002), "The Influence of Home-Based Reading Interactions on 5-Year-Olds' Reading Motivations and Early Literacy Development". Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 17, pp. 318-337.

STOLCKE, Verena. (1988), Coffee Planters, Workers and Wives: Class Conflict and Gender Relations on São Paulo Plantations, 1850-1980. New York, St. Martin's Press.

TRUZZI, Oswaldo. (2000), Café e Indústria: São Carlos 1850-1950. 2ª ed. São Carlos, EDUFSCar.

_____ (org.). (2004), Fontes Estatístico-Nominativas da Propriedade Rural em São Carlos (1873-1940). São Carlos, EDUFSCar.

_____e KERBAUY, Maria Teresa Miceli. (2000), "Mobilidade e Política: Considerações sobre a Participação de Imigrantes e seus Descendentes em Cidades Médias do Interior Paulista". Teoria & Pesquisa, no 32-35, pp. 157-179.

_____; NUNES, Paulo Reali e TILKIAN, Ricardo. (2008), Café, Indústria e Conhecimento: São Carlos, uma História de 150 anos. São Carlos, EdUFSCar/ São Paulo, Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo.

WISSENBACH, Maria Cristina Cortez. (1998), "Da escravidão à liberdade: dimensões de uma privacidade possível", in Sevcenko, N. (org.), História da Vida Privada no Brasil 3. República: Da Belle Époque à Era do Rádio. São Paulo, Companhia das Letras.

* Earlier versions of this article were presented at the XVI Encontro Nacional de Estudos Populacionais in 2008, and in the seminar "Imigração e raça na conformação das identidades e da estrutura social paulista", at the Federal University of São Carlos, also in 2008. I am grateful for the comments of participants in both events, especially Sérgio Nadalin and Oswaldo Truzzi. I also thank the staff of the Fundação Pró-Memória de São Carlos for their help. Daniela Barcellos helped with the organization of the database used here. This research is supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).