My SciELO

Brazilian Political Science Review (Online)

On-line version ISSN 1981-3821

Braz. political sci. rev. (Online) vol.5 no.se Rio de Janeiro 2010

Private security and the state in Latin America: the case of Mexico City1

Markus-Michael Müller

Centre for Area Studies, Universität Leipzig, Germany

Replicated from Brazilian Political Science Review (Online), Rio de Janeiro, v.4, n.1, 2010.

ABSTRACT

This article addresses the relationship between the privatization of security and the State in contemporary Mexico City. By presenting an analysis of the development of the local private security market, its regulatory framework and the problems stemming from inefficient enforcement of legal standards, it demonstrates that private security in Mexico City is not beyond the State. Rather, through formal and informal practices, the local state and its public security agencies play a central role within the recent transformations of local security provision.

Keywords: Private security; Security governance; Public security; Informality; Mexico City.

Introduction

In their now "classic" article The future of policing (1996), David Bayley and Clifford Shearing (1996, 586) observed that

(â¦) in the past 30 years the state's monopoly on policing has been broken by the creation of a host of private and community-based agencies that prevent crime, deter criminality, catch law-breakers, investigate offences, and stop conflict.

This quotation was one of the first manifestations of what has been discussed in the related literature on policing and security provision as the "transformation thesis" (Jones and Newburn 2002). It reflected the growing awareness that a (re)emergence of private policing and a related transformation of the relationship between public and private security actors was underway. In fact, by the 1960s, public police were already outnumbered by private security employees on a global scale (Jones and Newburn 2002, 133-34), and in the early 1980s, the ratio of public to private police in countries such as the United States was already 1:2 (Johnston 2007, 28). This trend continued throughout the following decades, leading to the constitution of a global private security market that is currently valued at about US$ 165 billion, with an expected annual growth rate of 8% (Abrahamsen and Williams 2009, 1). In this regard, a recent publication observed: "Indeed, so extensive has commercial security become in some societies that it appears to have significantly outstripped the public police in its size and the finances that underpin it" (Jones and Newburn 2006a, 6). Whereas initially this trend towards the privatization of security provision was closely related to the "rise of mass private property" in countries such as the United States (Shearing and Stenning 1983), the global spread of neoliberalism, and the related privatization and deregulation of economies and state services - including resulting patterns of social polarization and fragmentation - contributed to a substantial expansion of private security throughout the so-called developing and transitional countries of the Global South (Weiss 2007). This expansion received further stimulus from serious problems of the police forces (frequently more part of the problem than of the solution) in many states throughout these parts of the world. As Ian Loader and Neil Walker (2007, 23) summed it up in a paradigmatic way:

In those societies with weak or failing states, or undergoing transition, the public police are not the only or main security actor, nor can they lay claim to a monopoly over legitimate force inside their territory. [â¦] In these contexts, those who can afford to have, once more, fled behind walls, venturing from their residential enclosures only to make passage to other protected work and leisure domains.

As a consequence of these global developments, a number of leading scholars within the field of policing and security studies recognized the necessity of developing new concepts and analytical frameworks capable of understanding this transformation of security provision and its increasing move "beyond the state." The most prominent analytical move in this regard has been the introduction of a governance perspective on security provision. As Les Johnston and Clifford Shearing (2003, 10) stated: "The conflation of policing with state police is now restricting our view of what is being done to govern security under other auspices". The solution they proposed - and which other scholars followed - was to replace the classic term "policing" with the notion of "security governance" in order to capture the provision of security "beyond the state." In fact, the concept of security governance has become a dominant analytical tool for understanding the increasing privatization of security provision and the related pluralization of security actors throughout the world (see for example Chojnacki and BranoviÄ 2007; Bryden 2006; Wood and Dûpont 2006; Wood and Font 2007; Krahmann 2003). However, whereas many of the proponents of the security governance perspective argue that the abovementioned developments moved the provision of security increasingly "beyond the state" and caused "a repositioning of the state in relation to the plurality of agents and agencies now involved in the 'governance of security'" (Loader and Walker 2007, 120), frequently assuming an erosion of state power itself, other studies indicate that the dichotomizing perspective which informs much of the security governance literature, where security is either provided by public or by private actors, misses the complexities and ambivalences inherent in contemporary patterns of security provision. In this regard, Lucia Zedner (2009, 101) declared that

(â¦) the relationships between state and corporate players are increasingly complex and the line between public and private ever more difficult to draw. The resultant hybrid forms of 'state-corporate symbiosis' or 'grey policing' further blur the distinction between public and private.

From a more analytical-conceptual perspective, Rita Abrahamsen and Michael C. Williams (2009, 2) introduced the notion of security assemblages in order to capture these "hybrid" or "grey" forms of public-private interaction. They define security assemblages as

(â¦) settings where a range of different global and local, public and private security agents and normativities interact, cooperate and compete to produce new institutions, practices, and forms of security governance. As such, what is at stake in ''security privatization'' is much more than a simple transfer of previously public functions to private actors. Instead, these developments indicate important developments in the relationship between security and the sovereign state, structures of political power and authority, and the operations of global capital. In this sense, security governance is increasingly beyond the state, and is entwined with a broader rearticulation of public-private and global-local relations.

This article aims to contribute to this debate on the privatization of security and the resulting public-private relationship from the vantage point of Latin America, a world region which, throughout the last two decades, witnessed a dramatic increase in crime and violence. This development, which is due to the high degree of urbanization throughout the region, has a predominantly urban dimension (see for example Koonings and Kruijt 2007; Rotker 2002; Caldeira 2000), and contributed to the reproduction and acceleration of the aforementioned pattern of the privatization of security provision in cities throughout Latin America. As Miguel Angel Centeno (2002, 6-7) correctly observed:

With regard to the maintenance of social or civil order, citizens living in any major Latin American city increasingly find themselves victims to crime and are turning to privatized protection. For the rich, these services may be provided by the booming security industry. For the very poor this may involve reluctant membership in crude protection rackets.

However, and notwithstanding the fact that the importance of the "booming security industry" is widely acknowledged, this topic received strikingly little scholarly attention when compared to other dimensions of the local (in)security panorama, such as the local police forces or organized crime (but see Arias 2009; Ungar 2007; Wood and Cardia 2006; Caldeira 2000). As Mark Ungar (2007, 20) stated: "Although governments and scholars alike have recognized this growth, there has been very little concerted study of its causes, patterns and impact." By offering an analysis of the privatization of security provision in Mexico City - a paradigmatic Latin American setting - this article not only intends to offer empirical insights regarding the increasing privatization and commodification of security provision in Latin America, but also seeks to contribute to the abovementioned debates on security governance by demonstrating that the observable growth of private security in Mexico City is not "beyond the state." Rather, through existing legislation, formal and informal patterns of interaction, as well as through the semi-privatization of public policing, the Mexican state is a central actor directly involved in the local transformation of security provision, the related re-articulation of public-private relations, and the central problems associated with this development.

Against this background, the article is organized as follows: I first offer a brief discussion of the data and sources this article draws upon. Next, I address the development of the private security market in Mexico City. Then, I analyze the legal regulation of private security provision in Mexico City. In fourth place, I turn to the informal dimension of the local private security market and the involvement of private security in illegal activities. The next section addresses the problems resulting from the semi-privatization of public police, and in the concluding section, I summarize the main findings of the study.

A Note on Sources and Scope

The findings of this article are based on the following sources: First of all, they are derived from fifteen interviews with members of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), members of the local administration of justice and members of private security companies conducted in Mexico City between 2006 and 2009. I supplemented the interview material with systematic newspaper research on the topic of private security in Mexico City for the period 2005-2008. In addition to this, although the topic of private security received comparatively little attention when compared to other issues of Mexico City's current (in)security problems, some scholarly studies addressed this topic and were included in this article. Against this background, the findings of this article are undeniably tentative. In order to present a more comprehensive assessment of private security in contemporary Mexico City, more research on this topic is necessary. Nonetheless, I am convinced that despite their descriptive and tentative nature, these findings offer us more than just a glimpse of the central role of the state within the privatization of security provision in contemporary Mexico City. Additionally, as there are no systematic studies on the privatization of security provision so far, the material presented in the following pages may serve as an important indication of the unfolding of private security in Mexico City, which future studies can draw upon in order to make larger and more substantial theoretical and analytical claims on this subject. Against this background, we can now turn to an analysis of the privatization of security provision in contemporary Mexico City.

The Development of Private Security in Mexico City

As in many other Latin American countries, the recent processes of democratization in Mexico are accompanied by a dramatic rise in crime and insecurity. There is a common agreement among scholars dealing with the local insecurity problems that the immediate aftermath of the 1994 economic crisis witnessed a significant increase in the number of officially reported crimes, predominantly robbery and theft, during the period between 1994 and 1997 (Shirk and Ríos Cázares 2007, 8; Zepeda 2004, 24, 36; Bailey and Chabat 2002, 3; Ruiz Harrel 1998). Although, at least according to official data, crime rates have declined since the late 1990s, they are still high compared with the historical experience of criminality in Mexico, and recent victimization studies even question the officially proclaimed decline of crime rates (Alvarado 2007). One important factor contributing to this situation can be identified in the Mexican police forces. Despite the impressive fact that there are more than 1,000 different police units with approximately 410,000 policemen and women operating in the country, their overall contribution to an improvement of the local security environment is more than doubtful. The main reasons behind this can be identified in the general problems of the local police organizations, which can be summarized as the lack of adequate human resources and training, high turnover rates, a lack of vocational ethics, deficient and outdated equipment, low salaries, corruption, the absence of a clear normative framework of action, and the frequently direct participation of police agents in organized (and unorganized) crime and violence (Müller forthcoming; 2006; Suárez de Garay 2006, 29-32; Davis 2006; López Portillo Vargas 2004; 2002; Bailey and Chabat 2002; Martínez de Murguía 1999; Ruiz Harrell 1998, 57-69).

The resulting incapacity of the Mexican state to provide substantial degrees of protection and safety for its citizens has been identified as the principle cause behind the growth of private security (Reames 2008, 114). In fact, the development of a private security market in Mexico is a quite recent phenomenon. Whereas in 1970, only forty registered private security companies were operating in the country, their number reached more than 1,400 companies in 2000. The number of companies began to grow significantly in the aftermath of the 1994 economic crisis and because of related perceptions of rising crime in the mid 1990s, contributing to an annual business volume of about US$ 200 million (Regallado Santillán 2002, 187-188). The most significant increase in private security companies operating in Mexico occurred between 1998 and 1999, when their number increased by 40% (Reames 2008, 114; Bailey and Chabat 2002, 24).

This national development pattern was paralleled in Mexico City. Since 1994, rising levels of crime in the capital created a prosperous environment for a veritable private security boom. This process received further stimuli from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) integration process. On the one hand, the NAFTA process brought more foreign firms to the country (and Mexico City), firms whose executives were frequent targets of kidnappings and petty theft. These firms therefore searched for alternative security measures such as contracting private security companies. On the other hand, in the immediate post-NAFTA period, foreign security companies discovered the potential of the local private security market, which offered lucrative profits for comparatively low capital investment (Davis 2003, 21).

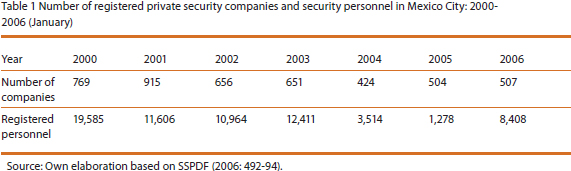

In an effort to coordinate and regulate the booming private security industry in Mexico City, in 1994 the local government created the Private Security Services Registration Department (Dirección de Registro de Servicios Privados de Seguridad), which registered 2,122 private security companies for 1994 (Davis 2003, 21). In the following decade, this number decreased to about 500 registered companies in 2006. The highest decrease in the total number of registered companies occurred between 2001 and 2004 and was reflected in a substantial drop in the number of registered private security personnel. Whereas in 2004, some 12,411 people were officially registered as working for private security companies in Mexico City, the data for the following year only counts 3,514 employees (Table 1).

This decline in the total of the officially registered private security companies can be attributed to two factors: First of all, since the late 1990s, new laws aimed at regulating the local security companies were enacted, and despite the sometimes serious enforcement problems (see below), many private security companies were not able to comply with the required standards and did not receive permission to keep their business in operation. A second and closely related factor is that besides the local legal regulation of the private security sector, there exists an additional federal law. Article 1 of the Ley Federal de Seguridad Privada (Federal Law of Private Security) establishes that federal regulation is applied whenever a private security company is offering its services in more than one federal state (see also Arias 2009, 61; Siller Blanco 2002, 106-7). In general, it can be assumed that the federal law, which aims at standardizing the existing different local regulatory systems (see especially Article 7, paragraph 5), poses lower legal and regulatory barriers for operating a private security business than the local legislation. For example, whereas the federal law only makes a general reference to "private security," the local law (see below) makes a distinction between different types of private security and the related necessary qualifications for people offering these services (La Jornada 2008a). Leaving aside the question of tax evasion, these features of the federal law are an important factor behind the decision of many private security companies offering their services in Mexico City, to move to neighboring states, such as the State of Mexico, in order to avoid local legal regulations.

If we compare the officially registered personnel employed by private security companies in Mexico City (8,408 employees) with the 30,800 members of the Preventive Police, the ratio between public and private police in Mexico City is about 3.6 Preventive Police officers for every private security agent. However, this is deceiving in its high ratio of public to private police. Despite the fact that the number of officially registered private security companies significantly declined during the last decade, this does not mean that most of those companies went out of business. Instead, as we will see shortly, a great number of these companies formed part of a growing local informal private security market. The number of companies offering their services on this market by far exceeds that of the formal market - and that of the public police forces. Before I address this informal side of private security in Mexico City, I want to take a closer look at the existing legal regulation of the formal local security market, as this area is of crucial importance for assessing the role of the state within the privatization of security provision in Mexico City.

The Legal Regulation of Private Security in Mexico City

In Mexico City, the Secretaría de Segurida Pública del Distrito Federal (Secretary of Public Security for the Federal District (SSPDF)) is the authority responsible for the regulation of the local private security forces. This was established in 1996 when, after a brief period in which the Attorney General of the Federal District (Procuraduría General de Justicia del Distrito Federal, PGJDF) held the responsibility for the Dirección de Seguridad Privada (Department of Private Security), the latter department was transferred to the SSPDF where it remains until this day under the name of Dirección Ejecutiva de Seguridad Privada (Executive Department of Private Security). A first substantial legal effort to regulate the local private security sector occurred in 1999 with the passing of the Ley de los Servicios de Seguridad Prestados por Empresas Privadas (Law for Security Services provided by Private Enterprises). This law was replaced in 2005, when the local legislative assembly enacted the Ley de Seguridad Privada para el Distrito Federal (Private Security Law for the Federal District), which is the city's main instrument for the current regulation of private security. The Private Security Law of the Federal District regulates a wide range of private security services, which include surveillance, vigilance, protection of persons and property but also includes detective tasks like the localization and information gathering on persons and property (Article 3). In what follows, I will give a brief overview of some of the most important dimensions of the law regarding the regulation of private security in general and the relation between public and private security in particular.

With regard to the relationship between public and private security, the law explicitly defines the provision of private security as complementary and auxiliary to public security, requiring private security forces to collaborate with local authorities in the investigation and prosecution of delinquency by providing agents and information. Additionally, private security must support the police in cases of (natural) disasters and accidents (Article 3, paragraph XXVII; Articles 4; 6, paragraph IV; Article 31; Article 32). This legally defined auxiliary character of private security in Mexico City dates back to 1941. In March of that year, the local government presented the Reglamento del Cuerpo de Veladores Auxiliares de la Policía Preventiva del Distrito Federal (Regulation of the Body of Auxiliary Night Watchmen of the Preventative Police), defining, in Article 1, that all members of the night watchmen (veladores) are legally auxiliary members of the preventive police. According to Lorenzo Xavier Aldrete Bernal (2006, 19), ever since this definition, commercial vigilance or protection activity has been defined as auxiliary to the provision of public security.

Despite its auxiliary character, the current legislation states that the provision of private security must not interfere with functions which are reserved exclusively for the armed forces or the police (Article 36, I). The law also requires that the uniforms and vehicles used by private security companies must be distinguishable from those of the police and the armed forces, a distinction which, among other things, requires that the word "security" may only be used with the addition of "private." The law also declares the owners and employees of private security companies must not be active members of the armed forces or the police (Article 13, paragraph V; Article 14, paragraph VIa; Article 17, paragraph IX; Article 18, paragraph VII; Article 36, paragraphs I-VII).

The obligation of private security to protect and respect human rights and the rule of law, another important factor regarding the regulation of private security, is explicitly recognized in article 6, paragraph I of the law. This article states that the provision of private security is grounded in the principles of legality and the respect for human rights. Furthermore, the local public security law also requires that neither suppliers nor employees of private security firms may have been convicted of an intentional crime and sentenced to a prison term longer than a year. Furthermore, they must not have been discharged from the police or military service because of contravention, negligent endangerment of private persons, dishonorable behavior, consumption of alcohol or drugs, betrayal of secrets, the presentation of false documents or extortion of subordinates (Article 13, paragraphs VI - VII; Article 17, paragraphs XI and XIII; Article 18, paragraph IX and XI).

If carrying firearms, private security employees must present a valid firearms certificate issued by the Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional (National Defense Ministry) and must be registered in the national firearms register (Article. 14, paragraph Ih; Article 15, paragraph IVe; Article 16, paragraph IVc; Article 17, paragraph IV). In addition, the type of weapon and ammunition used must be communicated to the SSPDF (Article 14, paragraph IV; Article 24, paragraph X). Furthermore, the law requires that the minimum training for private security employees must include oral persuasion, the use of firearms, non lethal weapons and fight training (Article 28, paragraph I-IV).

This brief review of the regulatory framework already indicates that from a formal-legal perspective, private security in Mexico City is not beyond the state. First of all the state, through the SSPDF, is responsible for the legal supervision of private security, which is more demanding than the respective regulation in countries such as Canada (Rigakos and Leung 2006) or the United Kingdom. In the latter case, for example, the Private Security Act of 2001 limits itself to a voluntary registration scheme, with firms voluntarily submitting themselves for regulation (Jones and Newburn 2006b, 42). In addition to this, the provision of private security is legally defined as complementary and auxiliary to public security, implicitly establishing a clear hierarchy of security providers with public security on top - a more than just symbolic affirmation of role of the state in supervising private security actors. However, and notwithstanding this legal framework, the reality of the local private security market stands in striking contrast to the impressive legal obligations, whose strict enforcement seems to be the exception rather than the rule. This contributes to the emergence and consolidation of a highly unregulated and predominately informal private security market in Mexico City, which I will analyze next.

Regulative Capacity and the Informal Security Market

During the last decade, due to the prevailing local security problems, Mexico not only witnessed the expansion of the formal private security market. The country also witnessed the emergence of a highly informalized and unregulated private security sector. Although the size of this informal sector is difficult to estimate, experts calculate that some 20,000 private security companies are offering their services throughout the country. Only about 5,000 of these firms are officially registered (La Jornada 2005a; Milenio 2005)2. In a recent interview, the director of one the biggest private security employer organizations in Mexico additionally claimed that about 80% of the whole private security market in Mexico operates under conditions of informality (La Jornada 2008b, see also La Jornada 2008c).

Asked about the size of the informal private security sector, a high ranking member of the SSPDF's Executive Department of Private Security, simply declared that "The existence of irregular private security companies is undeniable, although it is impossible to give a concrete number of how many there are" (interview October 2008). However, other local experts interviewed for this study calculated with an equally high ratio of unregulated private security companies in Mexico City than the numbers presented above on Mexico, and a newspaper article referred to about 1,400 private security enterprises operating in the metropolitan area (Milenio 2006). This is nearly twice as much as the officially registered number3. In addition, a study of the private security company Securitas indicates that in the metropolitan area, some 250,000 people are working for the private security industry (Wondratschke 2004, 79) - three times more than the personnel officially registered by the SSPDF.

Even if we do not possess an accurate account of the real size of the informal private security market in Mexico City, the available information indicates that this informal market is much bigger than the formal one, an observation which can be attributed to a set of substantial shortcomings of the legal regulation and its enforcement. Indeed, one major factor contributing to the growth of an informal and unregulated private security market is the limited control capacities of the SSPDF. In fact, the judgment of Regallado Santillán (2002, 184) that in Mexico "the government does not have sufficient resources to effectively police this industry" also holds true for Mexico City. Here, according to official information, the Dirección de Seguridad Privada has a total of about 50 inspectors for the entire local private security market, making a strict enforcement of the legal standards difficult4. However, it is not only the limited number of personnel which has a negative impact on the enforceability of the local private security law. The quality of the inspections themselves is an additional problem, as the visits by the inspectors are frequently marked by corruption and the bribing of the inspectors.

A telling account of this situation was given in one of my interviews with a private security provider. He explained that the majority of these companies, most of all the small-and medium-sized ones, are highly nontransparent in their business operations and most often do not meet the standards formulated in the local private security law. According to his perception, this is made possible through the way in which official private security inspectors handle their inspections. He mentioned that it is a common practice in Mexico City for the inspectors of the SSPDF to turn a blind eye to irregularities of the inspected companies as long as the latter are willing to offer a financial reward (interview July 2007). A similar point was made by an ex-member of the local security apparatus. He identified the expenditures for bribing local inspectors as one of the main reasons why many small private security companies try to avoid legal regulation and opt for operating in the informal market. In addition, he mentioned that besides the permanent payments for bribes, the normal expenditures, resulting from a strict compliance of the legal regulation - including payments for drug-tests and psychological examinations of the employees - as well as highly bureaucratic procedures, such as the annual preparation of their economic performances for the SSPDF, are further motivations for small- and medium-sized private security entrepreneurs to avoid the formal security market and to opt for an informal business. This move, however, would exclude them from more lucrative jobs, such as the protection of shopping malls or international companies. These would prefer big national or international private security firms, such as those organized in the private security employer's association, the National Council of Private Security (Consejo Nacional de Seguridad Privada, CNSP), which demand that their members meet the minimum standards of their service provision (interview July 2007).

The equation, implicit in the aforementioned perception of my informant, of bigger local and national private security companies, such as the companies organized in the CNSP, with stricter compliance with legal standards must be approached with skepticism. Even if the bigger names in the local private security market supposedly provide higher quality services, for example through better training and equipment, the economic incentives for evading some requirements of the legal regulation also seem appealing to the bigger names in the business. As the local director of an international private security company explained in an interview that many private security firms, including big ones, frequently tend to reduce their tax payments by registering a lower number of employees than they actually employ: "Those that have 100 employees say that they have 60, those that have 1,000 say that they employ 600, from those that have 10,000, only 5,000 are registered. Everyone tries to evade the law" (quoted in Wondratschke 2004, 84, emphasis added).

The lax inspections, in combination with the limited control capacities of the SSPDF, not only contribute to the growth and consolidation of an informal private security sector, they are furthermore responsible for the predominantly reactive character of the regulatory activities. Most of the serious enforcement and inspection efforts only happen when citizens or competing security companies report infringements, or when a criminal incident involves private security forces and receives broad media coverage. Once an investigation is started other irregularities are frequently detected. To give a paradigmatic example, in August 2005, a cash transport by the private security company Bissa was attacked in Mexico City, and a guard was killed. Investigations revealed that the company not only had hired active police members of the State of Mexico, which is a violation of the local public security law, but moreover, that the company's license for operating in the Federal District had not been renewed for more than four years (La Jornada 2005b).

The existence of these regulatory problems, aggravated by insufficient human resources, the persistence of bribing, as well as the predominantly reactive character of controls, also reveals that political interests are involved in the persistence of these practices. On the one hand, although many politicians are aware of the problems of the private security market, they fear that strict enforcement is a politically risky game, as it threatens to alienate potential voters. The political dilemma resulting from such calculations was expressed in an informal conversation with a local congress member who participated in the formulation of the current private security law. She admitted that a stricter regulation of private security companies would certainly be a good thing. But, she went on to explain, regulation should not hinder the city's poor inhabitants from engaging in private security, as this was one of the most accessible sources of income. Not only could too many legal barriers easily motivate them to engage in organized criminality, in addition, a strict enforcement would also mean that she herself could have a problem with her popular local electoral base (informal conversation, October 2006).

On the other hand, among all other contemporary security issues, due to the lack of both public and academic debates on private security, the topic of private security does not rank high on the security agenda of local politicians, as engaging in issues of private policing offers little political gains. As the security director of a big Mexican shopping mall chain explained, according to his work experience, there seems to be no political will for better control and regulation of the private security firms by the local authorities. Instead, they would prefer to invest their resources into more "visible" measures:

Yes, there is a lack of control. It is a problem for the secretaries of public security to control the private security companies. They can't and they don't want to either. It goes both ways. More than half of the private security companies are completely out of control. So how do you regulate all of this? How can we assure that the service they provide is of quality? Very few companies in Mexico are professional. Only 5% of the companies are professional in a sector which has thousands upon thousands of such businesses. [â¦] There are no resources for regulation. [â¦] It costs money that they don't want to spend on these things. They prefer to spend their resources on things that get more media attention. (Interview March 2008)

Another dimension through which politics enter the private security market consists of cases where representatives of public institutions contract private security on a tendential clientelistic basis, favoring companies of friends or political companions. For example, in August 2004, the financial accountability institution of the Federal District, the Contraloría General des Distrito Federal, started an investigation against the head of the administration of the Miguel Hidalgo borough, accusing him of having contracted a private security company (owned by one of his ex-employees) to protect the local public institutions, instead of contracting the Auxiliary Police as demanded by the Statute of the Mexico City government (La Jornada 2004b). Finally, it is a common feature of the informal private security market in Mexico City that police officers are moonlighting by offering their protection services to merchants or entire neighborhoods as informal private security providers (Müller 2009).

All of the above mentioned factors, but most of all the persistence of corruption and bribing, seriously limit the de facto control capabilities of the local regulatory architecture. As Diane E. Davis (2003, 22) correctly pointed out, "formal laws do little to regulate private police in a country where the regulators - i.e. the public police - themselves are corrupt". From a more analytical perspective, the aforementioned findings additionally point towards the central role of the state in the constitution and "regulation" of this informal segment of the private security market. Through the active engagement and participation of state officials in such practices (bribing, corruption, clientelism, symbolic politics, informal security provision), public security actors, either as private rent-a-cops or as control agents willing to turn a blind eye on regulatory infractions, contribute decisively to the existence and perpetuation of an informal private security market and facilitate the involvement of private security personnel in illegal activities - a fact which I will address in the next section.

Private Security, Criminality and Violence

Although the information on this topic is limited, the available sources indicate that the engagement of private security companies in illegal and violent activities in Mexico is a common feature (Arias 2009, 55). As Graham H. Turbiville (2006, 8) stated: "Kidnapping, robbery, extortion, and coercion on behalf of various criminal, economic, and political agendas have been associated with Mexican private security, just as they have been with the often-complicit federal, state, and local serving police officers"5.

Private security personnel in Mexico City frequently act arbitrarily, violently and contravene any social norms that are supposed to organize and control urban life. Nonetheless, private security personnel involved in such acts are in general not sanctioned by state authorities. Bodyguards in particular are often linked to organized violence, e.g. they deliver decisive information for the kidnapping of their employer or persons in their employer's surroundings. Finally, there are many cases where private security was actively involved in muggings inside housing estates (Mendieta Jiménez 2006, 409-10). As Benjamin Reames (2008, 114-15) recently observed, due to the unregulated and informal character of most of the local private security companies, it is very likely that "some will engage in criminality instead of (or as a means of) protecting their clients, thus exacerbating the problem of insecurity". Engaging in criminal activities is often facilitated by existing connections between public and private security agents. According to a director of a local security advisory company, many of the private security guards are ex-police and military officers who have lost their jobs because of "inappropriate behavior." In many cases these people maintain their personal networks established inside the public security forces which serve as a perfect infrastructure for intelligence gathering and material and personnel supply for engaging in criminal activities such as kidnappings (interview July 2007, see also La Jornada 2008b). The attractiveness of such illegal activities for people employed in the private security sector can be, at least partly, explained by the low salaries paid in the private security sector. The average daily wage in the area of Mexico City is estimated to be 104 Pesos (about US$ 10) for an excessively long workday (Milenio 2006)6.

Another problematic point of interaction between public and private security forces in Mexico City can be identified in the competition and resulting violent encounters between public and private security forces over the question of who, at the local level, holds the monopoly of violence, encounters which frequently result in shootouts between the involved actors (Davis 2003, 22; 2006, 77). Additionally, the available information demonstrates that private security personnel in Mexico City are involved not only in criminal activity and open competition with the local police over the street-level monopoly of violence, but also in abusive behavior. A clear manifestation of this problem is the increase in the number of private security companies in Mexico City and the accompanying rising number of formal citizen complaints against them (Davis 2006, 77). These complaints not only indicate abusive and criminal conduct of private security guards but also inadequate personal recruitment and the low quality of training. According to the director of a recruitment consultancy, only about 30% of the registered private security companies offer their employees a training program through contracting qualified personnel with experience in the security business (Milenio 2007).

Despite the general increase in the number of complaints against private security guards, the persons most affected by this kind of abusive behavior are people belonging to marginalized groups of the population, such as children living in the streets of Mexico City. Already in 1997, Amnesty International (1997) reported the case of private security guards maltreating and threatening street children. Since then, the human rights organization did not report again on the topic, but other sources indicate that such behavior still exists and is not officially sanctioned. A more recent example of this pattern of behavior, which illustrates the acceptance of this behavior, was given in a letter to the editors of newspaper La Jornada. In this letter, the author reported that he intervened in a situation where a member of a private security company threatened and insulted a street child searching in a garbage can for something to eat. When he complained about this behavior and reported it to the director of the bus terminal, the director justified the security personnel's behavior and urged the man to leave (La Jornada 2004a).

Despite such (comparatively rare) cases of media coverage, according to local NGO activists, it must be assumed that the majority of such cases remain unreported. Confronted with the time- and money-consuming procedures involved in making a respective declaration at a Public Ministry agency, and due to the predominantly negative perceptions and experiences with the local law enforcement agencies, we cannot expect the victims of abuses committed by private security personnel to publicly denounce such cases - least of all those belonging to marginalized groups of the local population who can be expected to be the principal victims of such practices.

However, and notwithstanding the aforementioned problems associated with the activities of private security in Mexico City, it is undeniable that more and more people and companies are contracting private security companies in order to feel safer and more protected, or, as many interview partners indicated, just in order to comply with the conditions of insurance polices. This last point is particularly important. As an ex-member of the local police forces stated, many clients of private security in Mexico City are well aware of the low quality of the service provision, however, due to the conditions of many insurance companies, they have no other option than to contract a private security company. Therefore, "[t]hese companies that hire private security, are not interested in the quality of the service but only to contract out somebody to watch the door" (interview March 2008). In a similar vein, the security director of a big local shopping mall chain (introduced above) stated that due to the negative image of private security companies, he decided not to contract private security for security provision inside their shopping malls. Rather, private security guards protect less visible spaces such as the parking lots or the arrival of incoming goods. Inside the shopping malls, he only works with the Banking and Industrial Police (Policía Bancaria e Industrial (PBI)), which, according to his experience, "has a better image and is more trusted by our clients than private security." These observations not only suggest that public security seems to possess a higher degree of symbolic appeal for potential clients than private security guards. This interview passage also indicates another important aspect of the private security panorama in Mexico City: the existence of semi-private police forces, representing a specific national arrangement where "such security functions, which in other countries are now performed by private firms, are a joint function of government and industry in Mexico City" (Chevigny 1995, 233). The next section will take a closer look at this feature.

The Privatization of Public Policing: The Complementary Police

Besides its authority over the Mexico City Preventive Police, the SSPDF is also responsible for two police organizations "outside" the Preventive Police force, converting public security into a crucial actor involved in the commodification of security provision in Mexico City. These two police forces, which together compose the Complementary Police (Policía Complementaria (PC)), are the Policía Auxiliar (Auxiliary Police (PA)) and the Banking and Industrial Police mentioned above. Both organizations together employ nearly 45,000 police officers, which is obviously more than the 30.000 police officers of the Preventive Police force. The faculties and duties of the Complementary Police are defined in Article 43 of the Reglamento Interior of the SSPDF. This article states:

The Complementary Police offers protection services, custody, and the vigilance of persons, goods, values and real property for dependencies, entities and institutions of the federal executive, legislative and judicial powers and for the Federal District; for autonomous federal and local institutions as well as for physical and moral persons, through the payment of the equivalent that has been determined by the General Director, and which is to be published annually in the Official Gazette of the Federal District.

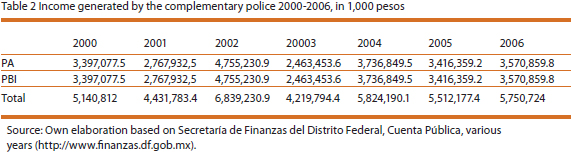

This implies that both complementary police forces can be legally contracted by public and private clients in order to guard their personal and commercial belongings (including buildings). Article 45 of the same document even specifies that these police forces can be contracted by the Mexico City boroughs for providing public security in public places within their respective territories (in practice, this refers most of all to the PA). Furthermore, in cases of emergency, the SSPDF can assign the Complementary Police to general tasks of maintaining the public order. An overview of the additional income generated for the government of the Federal District through the Complementary Police is given in Table 2.

The PA is composed of about 30,000 police officers, nearly the same number of active officers under its authority as the regular preventive police. Among other tasks, its faculties include the guarding of public buildings, the Transporte Colectivo (Metro) and the airport. In addition, it is frequently involved in special operations of the SSPDF. In 2006 the PA had 2,657 clients, most of them coming from the private sector (SSPDF 2006a, 105).

The PBI7 shares with the PA this semi-private character, as its services can also be contracted by both private and public agencies. However, it has a more limited service spectrum compared to the PA. It is specialized in guarding public and private enterprises and businesses, shopping malls, banks and financial institutions. The most important difference between the PA and the PBI is that, although the PBI is formally integrated into the SSPDF, it does not receive any kind of budget from the local government and is therefore totally self-financed through the request of its services:

The PBI is self-financed but not autonomous, since it has been incorporated into the structure of the Ministry of Public Security. It also receives no resources from the government of the Federal District; rather, it is obligated to turn over twenty percent of its earnings to the district's treasury. The government purchases patrol cars and equipment, while business and banks pay for officers' uniforms. The remaining eighty percent of PBI's earnings is almost entirely dedicated to the payroll. (Alvarado and Davis 2000, 37).

In 2006, the PBI protected 2,392 objects, including amongst others, installations of American Express; El Palacio de Hierro, S.A. de C.V.; Grupo Sanborns, S.A.; Nestlé México, S.A.; Siemens, S.A. and Sony Comercio de México, S.A., de C.V. (SSPDF 2006a, 133).

Interview partners from the private security sector frequently complained that the existence of the Complementary Police forces represents an illegitimate - state sponsored - intrusion into the local security market, thereby distorting competition and the "natural" operation of the market. However, as some of my interview partners indicated, the PC's basic competitive advantage is their direct link to SSPDF, which was expected to produce a more efficient and faster response in case of an emergency than the one expected from private security companies - a factor which was expected to produce a certain crime deterrence potential. Whereas the incorporation of the PC may have certain advantages for prospective clients, their institutional affiliation to the SSPDF also contributes to the reproduction of structural problems of the local police forces, such as corruption, police abuse or extortion (on these topics see Müller forthcoming; 2008; Davis 2006; Martínez de Murguía 1999) inside the PC. In this respect, it is telling that Alejandro Gertz Manero, ex-police chief of Mexico City, offered the following description of the PC:

Those policemen [of the Banking and Industrial Police] have been used by their police chiefs as if they were their private servants. They paid them what they wanted, while at the same time appropriating hundreds of millions of Pesos each year, either for their own benefice or in order to redistribute the money with their superiors. [â¦] Police chiefs, commanders [â¦] used the public mandate of the police and the officially generated income as if it was a private business. They obtained multimillions which made them public servants and extremely rich businessmen at the same time, with no accountability, without paying taxes, and by using the monopoly of the police in their favor - with the knowledge of all police chiefs and the entire political hierarchy. (Quoted in Azaola 2006, 39)

That these practices are not entirely a thing of the past became obvious when members of the PA recently went on hunger strike in order to protest against arbitrary practices of their superiors (Milenio 2009). Furthermore, local newspaper reports and documents from public authorities frequently report on the active participation of PC members in criminal and arbitrary activities (see for example SSPDF 2006b; Crónica de Hoy 2006; Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal 2003; Reforma 1999).

Conclusion

In this article I have demonstrated that due to the increase of crime and insecurity in contemporary Mexico City, private security companies have become important actors in the local security governance arrangements. However, as the empirical observations presented in this article indicate, the recent boom of private security in Mexico City cannot be interpreted solely as a move towards the governance of security "beyond the state." Through existing legislation, the local state not only defines private security as auxiliary to public security, it also claims responsibility for the regulation and legal oversight of private security companies and provides a clear and demanding regulatory framework in the form of the local private security law. Furthermore, the local public security apparatus, in particular the complementary police forces, that can be contracted by private actors, is also an active agent in the privatization and commodification of security provision. In addition to these formal aspects, the local state, in particular the police, also played a central role in the growth "regulation" of an informal private security market, whose size seems much larger than that of the formally regulated security market in Mexico City. Although, as indicated in the introduction, these findings are to a certain degree tentative, they nonetheless demonstrate that a dichotomist perspective on the privatization of security, which operates with static public-private categories and perceives the privatization of security as an erosion of state authority, misses the fact that "[w]hat we are witnessing then, is not so much a straightforward erosion of public authority, but rather a re-articulation of public/private [â¦] distinctions and relations" (Abrahamsen and Williams 2009, 12). In fact, as Jennifer Wood and Nancy Cardia (2006, 163) observed for Brazil, the practices of security provision in Mexico City identified in this article

(â¦) are difficult to explain in reference to the public/private distinction. Mentalities, and the strategies they inform, cut across sectors (commercial and non-commercial), whilst individual security actors participate in different sectors within different times and spaces (â¦).

Many of the findings presented in this article are not exclusive to Mexico, but have also been reported for other private security markets in contemporary Latin America (Arias 2009; Zanetic 2008; Frigo 2006; Wood and Cardic 2006; Caldeira 2000). However, and notwithstanding the omnipresence of private security guards in contemporary Latin American cities, studies on this topic are still rare, when compared to the now abundant literature on public policing (and its problems) in the region. In this respect, I want to conclude this article with a plea for more studies on the growing privatization and commercialization of security provision in contemporary Latin America - in particular empirical ones, interested in identifying and understanding the formal and informal place of the state within these processes. An increasing scholarly interest in this topic would make a substantial contribution to enhancing our knowledge on the complex nature of the security problems and "(un)rule of law" that is haunting large parts of the region7.

Notes

1 Research for this article was conducted between 2006 and 2009 within the context of the Research Center (SFB) 700 "Governance in areas of limited statehood - New modes of governance?", funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and located at the Freie Universität Berlin. http://www.sfb-governance.de

2 A similar ratio was already calculated for 1999, indicating that it has remained fairly stable since then (Bailey and Godson 1999, 24).

3 It is important to indicate that the metropolitan area, the so-called Zona Metropolitana del Valle de México (ZMVM), also includes neighboring municipalities of the states of Mexico and Hidalgo.

4 http://portal.ssp.df.gob.mx/Portal/SeguridadPrivada/EstadisticasSegPrivada.htm (accessed February 10, 2008).

5 A recent newspaper article revealed that the Federal Attorney General is investigating numerous cases where private security companies were used by drug traffickers for money laundering (La Jornada 2008d).

6 The low payment also contributes to an extremely high turnover rate in the Mexican private security sector. According to government information, between January and June 2007, 17,077 persons were registered as new entries into the National Register for Private Security Companies. For the same period, 19,069 people were deleted from the register for non-compliance with the required normative standards (Presidencia de la Republica 2007). It is telling that a street artist, who once worked in the private security sector, explained that he preferred his current source of income over his job in the security business as his work on the streets of Mexico City offers a better financial income, better working hours and a much safer workplace (interview June 2007).

7 As shown by Arturo Alvarado and Diane E. Davis (2000), the PBI was created in 1941. Originally it provided its services through a contracting system under which banks hired its staff to guard their branch offices. The banks in turn were responsible for the total cost of the service, which they paid directly to the Ministry of Public Security. This system was restructured in 1982 within the context of the bank nationalization under López Portillo. Due to an increase in bank robberies during the 1980s and early 1990s, the semi-public enterprise of Bank Security and Protection (Seguridad y Protección Bancaria (SEPROBAN)) was created to provide security for the now nationalized banks, but from the beginning it had only limited success. This was mainly due to the fact that its agents were not legally authorized to bear arms. This in turn forced banks and SEPROBAN to subcontract public police services from the PBI. The PBI, although it definitely lost its monopoly over the provision of bank security in recent years, is none the less the most important police corporation within this field.

Bibliographical References

Abrahamsen, Rita, and, Michael C. Williams. 2009. Security beyond the State: Global security assemblages in international politics. International Political Sociology 3 (1): 1-17.

Bernal Aldrete and Lorenzo Xavier. 2006. Propuesta de reforma constitucional en materia de seguridad privada en el estado Méxicano actual: Evolución e inconsistencias jurídicas. Mexico City: unpublished manuscript.

Alvarado, Arturo. 2007. Elements for a study of crime in Mexico City. In Towards a society under law. Citizens and their police in Latin America, ed. Joseph S. Tulchin and Meg Ruthenberg, 280-316. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Alvarado, Arturo, and Davis Diane E. 2000. Banking security in Mexico City: Mixing public and private police. In The public accountability of private police - Lessons from New York, Johannesburg and México City, ed. The Vera Institute of Justice, 34-45. New York: Vera Institute of Justice.

Amnesty International. 1997. Temor por la seguridad, AU 182/9719 de junio de 1997, http://asiapacific.amnesty.org/library/Index/ESLAMR410461997?open&of=ESL-2AM, accessed 17.03.2006.

Arias, Patricia. 2009. Seguridad privada en América Latina: El lucro y los dilemas de una regulación deficitaria. Santiago de Chile: FLACSO.

Azaola, Elena. 2006. Imagen y autoimagen de la policía de la Ciudad de México. Mexico City: Ediciones Coyoacán.

Bailey, John, and Chabat Jorge. 2002. Transnational crime and public security: Trends and issues. In Transnational crime and public security. Challenges to Mexico and the United States, ed. John Bailey and Jorge Chabat, 1-50. La Jolla: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego.

Bailey, John, and Godson Roy. 1999. Introduction. In Organized crime & democratic governability. Mexico and the U.S.-Mexican borderlands, ed. John Bailey and Roy Godson, 1-32. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Bayley, David, and Clifford Shearing. 1996. The future of policing. Law and Society Review 30 (3): 586-606.

Bryden, Alan. 2006. Approaching the privatisation of security from a security governance perspective. In Private actors and security governance, ed. Alan Bryden and Caparini, Marina 3-19. Münster: LIT

Caldeira, Teresa R. P. 2000. City of walls. Crime, segregation, and citizenship in São Paulo. Berkeley: California University Press.

Centeno, Miguel Angel. 2002. Blood and debt: War and the nation-state in Latin America. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Chevigny, Paul. 1995. Edge of the knife. Police violence in the Americas. New York: New Press.

Chojnacki, Sven, and Željko BranoviÄ. 2007. Privatisierung von Sicherheit? Formen von Sicherheits-Governance in Räumen begrenzter Staatlichkeit. Sicherheit und Frieden 25 (4): 163-169.

Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal (CDHDF). 2003. Boletín de prensa n°125/2003. http://www.cdhdf.org.mx/index.php?id=bol12503 (accessed November 12, 2007).

Crónica de Hoy. 2006. Policías del DF, implicados en el asesinato de militares, 22.5.2006.

Davis, Diane E. 2006. Undermining the rule of law: Democratization and the dark side of police reform in Mexico. Latin American Politics and Society 48 (1): 55-86.

___. 2003. Law enforcement in Mexico: Not yet under control. NACLA Report on the Americas 37 (2): 17-24.

Frigo, Edgardo. 2006. Seguridad privada en Latinoamérica: Situación y perspectivas. Buenos Aires: Instituto Latinoamericano de Seguridad y Democracia. http://www.ilsed.org/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=317&Itemid=44 (accessed March 1, 2008).

Johnston, Les. 2007. The trajectory of "Private policing." In Transformations of policing, ed. Alistair Henry and David J. Smith, 25-50. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Johnston, Les, and Clifford Shearing. 2003. Governing security: Explorations in policing and justice. London: Routledge.

Jones, Tim, and Trevor Newburn. 2006a. Understanding plural policing. In Plural policing. A comparative perspective, ed. Trevor Jones and Tim Newburn, 1-11. London: Routledge.

___. 2006b. The United Kingdom. In Plural policing. A comparative perspective, ed. Trevor Jones and Tim Newburn, 34-54. London: Routledge.

___. 2002. The transformation of policing? Understanding current trends in policing systems. British Journal of Criminology 41 (1): 129-46.

Koonings, Kees and Drik Kruijt, eds. 2007. Fractured cities. Social exclusion, urban violence and contested spaces in Latin America. London: Zed Books.

Krahmann, Elke. 2003. Conceptualising security governance. Cooperation and Conflict 38 (1):5-26.

La Jornada. 2008a. El GDF busca coordinación con el gobierno federal para aplicar ley de seguridad privada, April 6.

___. 2008b. Fuera de la normatividad, 80% de las empresas de seguridad privada del país, April 25.

___. 2008c. Al margen de la ley, casi 8 mil empresas de seguridad privada, August 6.

___. 2008d. Narcos usan a empresas de seguridad como fachada para lavar sus activos, June 16.

___. 2005a. Ilegales, unas 15 mil firmas de seguridad privada, señalan, November 28.

___. 2005b. Muere custodio de Bissa herido en intento de robo, August 3.

___. 2004a. Abusos en terminal de autobuses, November 22.

___. 2004b. Investiga la Contraloría gastos del convivio de Aboitiz en Cocoyoc, August 7.

Loader, Ian and Neil Walker. 2007. Civilizing security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

López Portillo Vargas, Ernesto. 2004. El caso México. In La Policía en los estados de derecho latinoamericanos. Un Proyecto internacional de investigación, ed. Kai Ambos, Juan-Luis Gómez Colomer and Richard Vogler, 390-421. Medellín: Ediciones Jurídicas Gustavo Ibáñez.

___. 2002. The police in Mexico: Political functions and needed reforms. In Transnational crime and public security. Challenges to Mexico and the United States, ed. John Bailey and Jorge Chabat, 109-136. La Jolla: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego.

Martínez de Murguía, Beatriz. 1999. La policía en México:¿Orden social o criminalidad? Mexico City: Planeta.

Mendieta Jiménez, Ernesto. 2006. Seguridad pública y seguridad privada ¿Complementarias o antagónicas? In Seguridad pública. Voces diversas en un enfoque multidisciplinario, ed. Pedro José Peñaloza, 409-436. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa.

Milenio. 2009. Protestarán con sangre los patitos feos, June 4.

___. 2007. Sólo 30 empresas capacitan personal, June 25.

___. 2006. Carecen de permiso los policías privados, December 17.

___. 2005. Ilegales el 80 por ciento de las empresas de seguridad privada, July.

Müller, Markus-Michael. forthcoming. Public security in the negotiated State. Policing in Latin America and beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

____. 2009. Policing the fragments. Public Security and the State in Mexico City. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Political Science, Freie Universität Berlin.

____. 2008. Fragmente des urbanen Regierens: Security governance in Mexiko-Stadt. In Verhandlungssache Mexiko-Stadt. Umkämpfte Räume, Stadtaneignungen und imaginarios urbanos, ed. Anne Becker, Olga Burkert, Anne Doose, Alexander Jachnow, and Marianna Poppitz, 131-144. Berlin: b_books.

____. 2006. Regieren durch (Un)Sicherheit? Die Rolle der Polizei im Kontext beschränkter Staatlichkeit in Mexiko. Peripherie. Zeitschrift für Politik und Ökonomie in der Dritten Welt no. 104:500-22.

Presidencia de la República. 2007. Primer Informe de Gobienro, http://primer.informe.gob.mx/ (accessed February 23, 2008).

Reames, Benjamin Nelson. 2008. Paths to fairness, effectiveness, and democratic policing in Mexico. In Comparative policing. The struggle for democratization, ed. M. R. Haberfield and Ibrahim Cerrah, 97-120. Los Angeles: Sage.

Reforma. 1999. Capturan a bancarios, June 24.

Regallado Santillán, J. 2002. Public security versus private security? In Transnational crime and public security. Challenges to Mexico and the United States, ed. John Bailey and Jorge Chabat, 181-191. La Jolla: Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California, San Diego.

Rigakos, George S., and Cherie Leung. 2006. Canada. In Plural policing. A comparative perspective, ed. Trevor Jones and Tim Newburn, 126-138. London: Routledge.

Rotker, Susan, ed. 2002. Citizens of fear. Urban violence in Latin America. New Brunswick: Brunswick University Press.

Ruiz Harrell, Rafael. 1998. Criminalidad y mal gobierno. Mexico City: Sansores & Aljure.

Shearing, Clifford, and Philip Stenning. 1983. Private security: Implications for social control. Social Problems 30 (5): 493-506.

Shirk, David A., and Alejandra Ríos Cázares. 2007. Introduction: Reforming the administration of justice in Mexico. In Reforming the administration of justice in Mexico, ed. Wayne A. Cornelius and David A. Shirk, 1-47. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Siller Blanco, Federico. 2002. La Segurida privada en México: Su normatividad. Revista de Administración Publica no. 106: 105-110.

Secretaría de Seguridad Pública del Distrito Federal (SSPDF). 2006a. Memoria institucional 2000-2006. Mexico City.

___. 2006b. Boletín informativo núm. 187, February 10.

Suárez de Garay, María Eigenia. 2006. Los policías: Una averiguación antropológica.Guadalajara. Guadalajara: Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Ocidente, Universidad de Guadalajara Centro Universitario de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades.

Turbiville, Graham H. 2006. Failing alternatives to public safety and atability. Crime & Justice no. 22, 4-9.

Ungar, Mark. 2007. The privatization of citizen security in Latin America: From elite guards to neighborhood vigilantes. Social Justice , vol 34, no. 3-4, 20-34

Weiss, Bob. 2007. Introduction: From cowboy detectives to soldiers of fortune: The recrudescence of primitive accumulation security and its contradictions on the new frontiers of capitalist expansion. Social Justice vol. 34, no. 3, 1-19.

Wondratschke, Claudia. 2004. Der Schwache Staat? Kriminalität und Sicherheit in Mexico City. Unpublished Diploma Thesis, Köln: Department of Political Science, Universität Köln.

Wood, Jennifer, and Nancy Cardia. 2006. Brazil. In Plural policing. A comparative perspective, ed. Trevor Jones and Tim Newburn, 139-168. London: Routledge.

Wood, Jennifer, and Benoit Dûpont, eds. 2006. Democracy, society and the governance of security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, Jennifer, and Enrique Font. 2007. Crafting the governance of security in Argentina: Engaging with global trends. In Crafting transnational policing: Police capacity-building and global policing reform, ed. Andrew Goldsmith and James Sheptycki, 329-356. Oxford: Hart.

Zanetic, André. 2008. The private security in Brazil: Some aspects related to the motivations, regulation and social implications of the sector. http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/etext/llilas/ilassa/2009/zanetic.pdf (accessed April 22, 2009).

Zedner, Lucia. 2009. Security. London: Routledge.

Zepeda Lecuona, Guillermo. 2004. Crimen sin castigo. Procuración de justicia penal y Ministerio Público en México. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Submitted in august 2009

Accepted in september 2010