My SciELO

Brazilian Political Science Review (Online)

On-line version ISSN 1981-3821

Braz. political sci. rev. (Online) vol.4 no.se Rio de Janeiro 2009

At what point does a legislature become institutionalized? The Mercosur Parliament's path*

Clarissa Dri

University of Bordeaux, France

ABSTRACT

The Mercosur Parliament was created in 2005 to represent the peoples of the region. The constitutive documents affirm the necessity of reinforcing and deepening integration and democracy within Mercosur through an efficient and balanced institutional structure. In order to examine the potential role of the Parliament in strengthening the institutional framework of the bloc, this paper aims to analyse its initial years of activity. What is the institutionalization level reached by the assembly so far? The research is grounded on the idea that the more institutionalized the legislature is, the more it will influence the political system. The article presents a comparative approach that considers the earliest steps of the European Parliament. In terms of methodology, the qualitative analysis is based on documental research and on direct observation of the Mercosur Parliament's meetings. The main conclusions are related to the limited level of institutionalization of this new assembly, in spite of its innovative features regarding the Mercosur structure, and to its similarity with the initial period of the European Parliament.

Keywords: Regional integration; Parliamentary institutionalization; Mercosur; European Union.

Introduction

The liberalization of global economic exchanges after the end of the Cold War led to several phenomena conceived of under the "globalization" label. The "regionalism" encouraged by some international financial institutions at this time consisted mostly in neoliberal recommendations aiming to stimulate free trade. Nonetheless, different types of regionalism, based not only on commercial issues, had already been discussed or experimented worldwide. The European Union is probably the most far-reaching and successful attempt at political integration which has sought to protect the zone from the economic effects of globalization, reducing territorial asymmetries and disconnecting the productive system from international prices.

In South America, Mercosur was conceived in the late 1980s by right-wing governments within the "new-regionalism" trend (Hettne and Inotai, 1994, 2). The formal objective is to create an economically integrated zone with free movement of goods, services, capital and labour, which implies common policies on product and social regulation. During the 1990s, however, some neoliberal governments concentrated efforts in the free trade part of the deal, trying to expand it to the whole continent following the North American proposal for the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). After the election of left-wing presidents in the early 2000s, Mercosur countries interrupted negotiations on the FTAA and the strategy of reinforcing integration within the bloc returned to political declarations. But reality did not match ambitious presidential discourse, and economic integration in Mercosur remains limited to free trade with some steps in the direction of a customs union. In terms of competences, there is no indication that states would give up the intergovernmental model and transfer certain policy-making areas to the regional ambit. In spite of this, some recent initiatives, like the organization of structural funds and the creation of the Mercosur Parliament (Parlasur), seem to reflect the will to transcend commercial aspect, leading integration to the political and social spheres.

The Parlasur Constitutive Protocol, signed in 2005, affirms the necessity of reinforcing and deepening the integration process. According to the document, it is essential to have an efficient and balanced institutional structure, which would permit the production of effective norms in an atmosphere of security and stability. In order to infer the potential role of the Parliament in strengthening the institutional structure of Mercosur, this paper aims to analyse its initial years of activity. The institutionalization level reached by the assembly until now can indicate its capacity to affect Mercosur policies and institutions. This assumption is grounded on the idea that the more institutionalized the legislature is, the more it will influence the political system. Consequently, the Parlasur will only be able to increase the institutional framework of integration if it displays certain valued rules, procedures, patterns of behaviour and powers that characterize parliamentary institutions in general. This article uses Peter Hall's (1986, 19) relational concept of institutions: they consist in formal rules, compliance procedures and standard operating practices that structure the relationship between individuals in various units of the polity and economy. The idea of institutionalization includes, thus, the process of creation and solidification of these structuring rules, procedures and practices.

It is clear that relations between parliamentary institutionalization and political influence are not the same as relations between the former and integration strength. Even if the Mercosur Parliament achieves an institutionalization level sufficient to have an effective bearing on the system, it does not mean it will search for deeper or broader integration. However, some indicators suggest that this could be precisely the case of Parlasur. Firstly, deputies are a priori more susceptible to detaching themselves from immediate national interests than ministers or other executive authorities. Secondly, the leading actors involved in the creation of this assembly have conceived it as a means of democratizing and reinforcing the integration process. Thirdly, the Parliament has already adopted at least two instruments typical of supranational organizations which are completely new in Mercosur: political groups ideologically organized and proportional representation. Lastly, the European experience shows that sitting in a supranational assembly contributes to a pro-integration perspective and that the increase of parliamentary powers results in more integration.

These premises explain the following research question: can the Mercosur Parliament be considered an institutionalized legislature? In order to evaluate the degree of institutionalization reached by the assembly so far, its current features are contrasted with institutionalization criteria presented by political science literature and with the characteristics displayed by the European Parliament in its initial decades. Qualitative research based on public documents produced by the Mercosur Parliament during its first three years of activity (December 2006 to December 2009) provided data to this analysis. They consist of recordings of proceedings of the monthly plenary sessions (minutes, verbatim reports, decisions adopted),1 as well as registers of the Brazilian representation's meetings,2 besides founding documents such as the Constitutive Protocol and the Rules of Procedure. Direct observations of Parlasur meetings conducted between March and April 2009 helped to support the sociological examination of the socialization process, as well as semi-structured interviews made with members of the Parliament and other Mercosur actors over the same period. Secondary sources were used to analyse the European Parliament, due to the relatively large number of studies on the topic.

The comparative approach considers the institutionalization events of both assemblies to provide an assessment of the current institutional design of the Mercosur Parliament. Although the features of the European Parliament (EP) are presented in the current stage, according to the Lisbon Treaty (2009), the earliest actions and movements of the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community (1952) and the European Economic Community Assembly (1958) have a special relevance. As the Mercosur parliamentary experience is just starting, the comparison cannot neglect the origins of the EP. But it has to consider, at the same time, the gradual achievements and the institutional changes of this Parliament until the current phase, in order to avoid a static reflection that would not take into account the dynamics of the integration processes. The comparison between the South American and European experiences appears to be a useful tool to interpret the parliamentary institutionalization process in the two regions (Seiler 2004, 107), even if the former is emphasised in this article. There are few examples of integration parliaments worldwide, and most of them are inspired in the European "model". The EP becomes, thus, an inevitable benchmark in this field. There is, however, a risk of artificially assimilating experiences when the comparative methodology is used to study similar phenomena produced in different realities (Vigour 2005, 160-1), as in this case. This is why this research highlights both similarities and differences between the European Parliament and the Mercosur Parliament: a comparative study that does not look for both resemblances and disparities will either empty the method (by excess of assimilation) or make useless the comparison (by excess of differentiation) (Sartori 1997, 209).

This paper proceeds as follows. The first part attempts to clarify the parliamentary institutionalization criteria with a review of the literature. The second part presents the main structure of Mercosur and the main steps leading to the creation of its assembly. The third part discusses the institutionalization level of the Parlasur, comparing it with the EP. This section is divided into four sub-sections, corresponding to the selected characteristics for institutionalization analysis in both legislatures: autonomy, complexity, socialization and attributions.

Institutionalization Criteria: From National Institutions To Supranational Parliaments

The hypothetical framework of this paper is based on the institutional approach to political science (Rhodes 1995), particularly on the new institutionalism (March and Olsen 1984; 1989; Hall and Taylor 1997; Orren and Skowronek 1994). Since the late 1970s, there has been a growing research interest in institutions among political scientists, after a period dominated by a non-institutional conception of political life. This movement, later described as "new institutionalism", mixes elements of old institutionalism with the non-institutional style. It emphasises the role of institutions in providing order and influencing changes in politics, without denying the importance of social context and the performance of individual actors (March and Olsen 1989, 17). Institutions are considered variables that structure future political choices, acting normatively and conducting decisions and interpretations. Accordingly, Parlasur should substantially affect political preferences in Mercosur and trigger new institutional reforms.

This conception includes historical institutionalism (Skocpol 1984; 1995), which assumes that institutions shape political actors' objectives and power relations. However, it does not mean that institutions are the only causes of outcomes, but one more element among the universe of political forces (Thelen and Steinmo 1992, 3). Institutional development is mainly understood by analysing trajectories, critical situations and unexpected consequences (Hall and Taylor 1997, 472). An institutional result produced in a certain social and historical context may not happen in different circumstances, so that small events can cause large and unforeseen effects. To this notion of "path dependence", Paul Pierson (2000) adds the idea of "increasing returns": costs to modify a decision accrue with time.3 Once an organization decides to follow a specific route, the costs of rethinking this option are high and increase as time passes. There will be moments for new choices, but the development of some institutional arrangements will complicate the renouncement of the initial option. These theories seem to adequately apply to the process of institutionalization of the Mercosur Parliament.

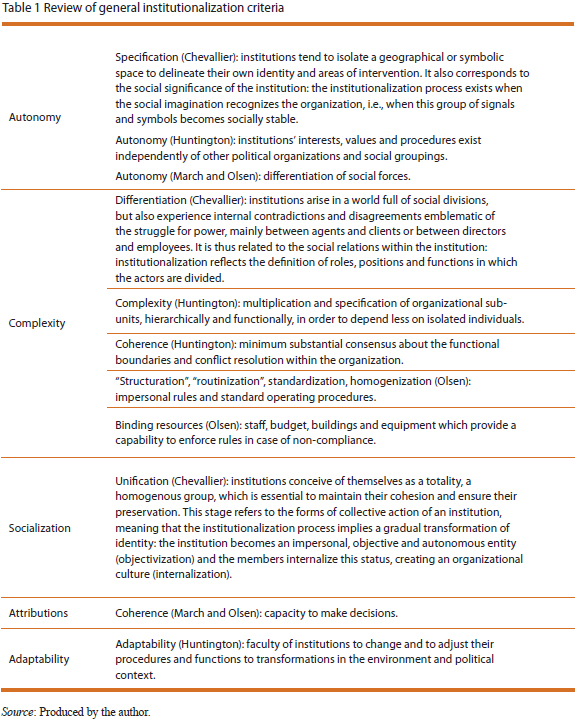

In a broad sense, institutionalization corresponds to the way in which social practices created in response to particular problems are solidified in aggregations of specific rules (Cox, quoted in Chevallier 1996, 17-18). Some authors have established specific criteria to identify this process. Jacques Chevallier affirms that institutions are processes of societal organization rather than stable social forms. This dialectical interpretation considers institutions in a dynamic way: they are not immutable, rigid and coherent, but a series of operations in permanent transformation. They derive from a persistent tension between instituted forms (l'institué) and instituting forces (l'instituant), where the latter is always destabilizing and reconstructing the former (Chevallier 1981, 8; 1996, 25). The institutionalization process reflects precisely a temporary stability which surpasses this contradiction. Therefore, institutions result from an evolutionary path distinguished by three essential movements: specification, differentiation and unification (Chevallier 1981, 14-17; 1996, 18-24). Nevertheless, these phases are not necessarily successive and can regularly be superposed by one another, with each institution developing its own pattern for the process. In Samuel Huntington's eyes, institutionalization of political organizations and procedures is an essential part of political development (Huntington 1965, 393), which comprises the processes of rationalization, integration, democratization and social mobilization. The presence of institutions defines the authority of the government (in the sense of political capacity) and cannot be dissociated from its economic links. Based on these assertions, he brings the institutionalization concept more vigorously to the political sphere and proposes four criteria to measure the value and the stability of a political system: adaptability, complexity, autonomy and coherence (Huntington 1965, 393-405; 1968, 13-24).4 Lastly, Johan Olsen (2001, 327) synthesizes the institutionalization segment of his research with James March into three dimensions: 1. structuration and routinization; 2. standardization, homogenization and authorization of codes of meaning, ways of reasoning and accounts; and 3. binding resources to values and worldviews. Institutions would also need coherence and autonomy to be considered political actors (March and Olsen 1989, 17). The table below combines all these criteria in a transversal classification that approximates similar ideas presented with a different denomination by the abovementioned authors.

The autonomy branch includes features used to differentiate the institution from the exterior world. Complexity includes all internal procedures related to the organic construction of the institution. Socialization refers to relations between the institution and its members. Attributions denote outcomes the institution is allowed and expected to deliver, while adaptability comprises concepts related to flexibility and reaction to new events.

The literature has also delineated institutionalization criteria for parliaments. A revival of legislative studies in Europe and the United States has taken place since the end of the 1960s. After a long period analysing parliaments' decline and the role of parties and Executive power in the decision-making process, some scholars began to investigate parliamentary transformations and institutional adjustment in order to fit in contemporary democracies. The large number of legislatures in the world and their historical persistence justifies some attention, mainly on a cross-national basis (Norton 1998, xii).

According to Nelson Polsby (1968, 144), institutionalization studies are legitimate because creating institutions is a necessary step to the viability of a political system and to its success in performing tasks on behalf of the population. Moreover, democracy and liberty depend on institutionalized representative forums containing political cleavages. Consequently, the author proposes three major characteristics to define an institutionalized organization: differentiation, organizational complexity and universalization (Polsby 1968, 145).

Jean Blondel (1973, 3) assumes that if legislatures are considered weak and resilient even if they are a symbol of liberal democracy, it is because the adaptation of modern representative ideals to reality was not entirely possible. Hence he proposes a re-evaluation of the legislature's role in the democratic process in conformity with contemporary practices. Success in achieving these renewed functions would depend on constitutional prerogatives and on internal and external constraints. The former emanate from the members or the structure of the assembly (time and size of the assembly, political and technical competence and infrastructure), while the latter derive from influence or coercion of outside elements (executive strength) (Blondel 1973, 45). In order to measure the influence of legislators, Blondel divides parliaments according to their role in the policy-making (Blondel 1973, 136-140). Also comparing parliaments' characteristics and functions from existing empiric bases, Michael Mezey (1979, 20) proposes a classification that corresponds to the masses' or the elite's expectations of the assembly. Depending on the strength of each of these conditions, parliaments can be active, vulnerable, reactive, marginal or minimal.

Based on studies by Blondel and Mezey, Philip Norton (1998, 8) proposes to consider external and internal elements to measure parliaments' capacity to influence government actions. The latter correspond to the institutionalization criteria: autonomy, universalism, adaptability and organizational complexity. Gary Copeland and Samuel Patterson (1994, 4-6), like Norton, try to combine functional and institutionalization analyses in order to explain institutional change, arguing that transformations in functions usually occasion transformations in the institution itself. They propose five dimensions for the study of legislatures' institutionalization process: autonomy, complexity, formality, uniformity and linkage to environment.

The institutionalization process also comprehends a human aspect: the socialization of actors. In spite of the various meanings that this expression can hold, like other basic sociological concepts, here it is understood as the process of interactions and symbol exchanges between the individual and society, and the consequent internalization of certain norms and values of the group.5 Political societies are only viable if the members share a minimum of common convictions about community allegiances and government legitimacy (Braud 1996, 193). Through assimilation, individuals try to change the environment to make it conform to their wishes; through accommodation, on the contrary, individuals modify personal convictions and practices to better adapt themselves to external circumstances (Percheron 1993, 32). Therefore, political socialization comprehends not only the inculcation of community principles among its members, but also the design of a societal political life by individual moods, manners and values: "what citizens believe and feel about politics both reflects and shapes the politics of their nation" (Dawson and Prewitt 1969, 4). As a process of identity construction — to socialize means to assume the belonging to a group — it should be interpreted in a dialectical perspective, which supposes interactive, multidirectional, gradual and non-linear characters.

Applied to parliaments, this process refers to the relation between deputies and the assembly as a whole. In this case, socialization can be temporary - if deputies only learn some rules of the game — or structural — if their values and worldviews change according to their experience in the parliament. In the first case, socialization is strategic to achieving certain objectives within the institution, vanishing as soon as the interest at its root disappears. In the second, socialization has a durable and more concrete effect on MPs' political visions and actions. The following table brings together the concepts related to parliamentary institutionalization presented above using the same structure as the first table for general institutionalization criteria.

Given that the objective of this paper is to apply political science's institutionalization patterns to the case of the Mercosur Parliament, institutionalization is understood here as the process of creation and maintenance of legal procedures and behavioural patterns which establish bases for institutional autonomy, complexity (which includes universalization), socialization and attributions. The notion of adaptability, even consisting of an important measure of institutional stability, cannot be considered yet, due to the brief existence of the Mercosur Parliament. Complexity and universalization are treated together because of their similar nature: transparency and publicity depend, to a large extent, on clear rules and internal organization, as well as the latter providing the legal framework for the improvement of universalist values. In other words, real complexity necessarily comprehends the fundamentals of universalization.

Since the institutions in question are integration parliaments, the criteria are adjusted to the context of absence of a traditional government and representation beyond the nation-state. Although the institutionalization theories described were developed to explain national parliaments, the outcomes may be applied to integration parliaments, especially if they are compared with legislatures rather than with international assemblies. In the case of the European Parliament, its legislative and control powers already satisfy such classification. When it comes to Parlasur, the situation is more complex. It displays important innovations in comparison to classic international assemblies, but its consultative status does not ensure the construction of a real parliament. Measuring Parlasur's institutional achievements with a national legislature perspective thus seems to be the first step to identifying their mutual distance.

Regionalism in South America and the Rise of Parlasur

The first concrete attempt towards regionalism in Latin America in the 20th century was the Latin American Free Trade Association (LAFTA). LAFTA was born in 1960 with the Montevideo Treaty, based on developmentalist assumptions derived from the US influence over the region (Santander 2007, 123-4) and conceived as a reaction to the European external tariff and agricultural protectionism (Mattli 1999, 140). The negotiations were sponsored by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), an agency of the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. In 1967, LAFTA was formed by Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela and Bolivia. Its formal objective was not only to achieve a free trade area but also to construct a long-term development model attentive to social issues. Nonetheless, the absence of delegate powers and the reduced institutional framework did not encourage more than an economic-oriented organization. The formation of a continental free trade area was skewed by difficulties regarding the asymmetric levels of industrialization between states and changes in national political regimes (nationalist and authoritarian forces governed many Latin America countries during the 1960s and 1970s). As a consequence, LAFTA was replaced by the Latin American Integration Association (LAIA), created in 1980 by the second Montevideo Treaty signed by the same states, plus Chile and Cuba (the latter having joined in 1998). The general objective of this new association, which still exists, is also to promote trade liberalization in the region, but through less ambitious and more flexible means. Its relatively complex institutional design and stable Secretariat contributed to enhance commercial negotiations among its members, which led to the signing of bilateral and multilateral agreements. The Asunción Treaty (1991), constitutive of Mercosur, is one of them (Bonilla 1991, 84-6).

Mercosur (the Spanish abbreviation for Common Market of the South) dialectically emerged as an element of continuity, for prolonging the integrationist efforts of the continent, and as a factor of change, for introducing a new economic, commercial and political context (Baptista 1998, 36). It was founded by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. Chile, Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Colombia are associated countries. Venezuela's Adhesion Protocol was approved in 2005 and awaits parliamentary ratification in Paraguay. The Asunción Treaty established the initial institutional guidelines, which were reviewed by the Ouro Preto Protocol (1994). Later on, the Olivos Protocol (2002), concerning dispute settlement, and the Constitutive Protocol of the Mercosur Parliament (2005) contributed to redefine the institutional design.

The Common Market Council (CMC) is responsible for the main political decisions and it is constituted by the presidents and ministers of foreign affairs. It is supported by the Committee of Permanent Representatives and meetings of different ministers. The Permanent Revision Court sits in Asunción. It is made up of five arbitrators who can be asked at any time to review ad hoc judgements or directly decide on conflicts between member-states, besides expressing consultative opinions by request of the decision-making bodies of Mercosur. The Common Market Group (CMG) and the Commerce Committee (MCC) are the executive branches, formed by diplomats and officials from ministries and central banks. The latter assists the former in policy-making regarding commercial issues. The structure of the Common Market Group includes a large number of thematic committees and working groups dealing with several matters: communication, environment, transport, health, employment, agriculture, industry etc. The Economic and Social Consultative Forum (ESCF) represents the economic and social sectors of Mercosur. It is formed by an equal number of representatives of each member-state, usually from trade unions and employers' associations. It can make recommendations to the Group. The Mercosur Secretariat, sited in Montevideo, carries out the main administrative and technical responsibilities.

In spite of a general inspiration from European regionalism and some structural similarities with the EU (Camargo 1999; Medeiros 2000), Mercosur is an intergovernmental organization. Its main goals are the creation of a common market, the promotion of social and economic development and the maintenance of democracy within member-states. In economic terms, it is currently seen as an "imperfect" customs union because of the various products excluded from the common external tariff. Mercosur rules do not have primacy over national law nor can they be applied to individuals or states without internalization in the national juridical systems. Decisions are highly centralized in national executives, mainly through irregular, itinerant and non-public meetings of diplomats and officials from different ministries.

In 2007, the Mercosur Parliament replaced the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC), which represented national parliaments and had consultative functions. Although LAFTA and LAIA did not display representative institutions, the Treaty for Cooperation, Development and Integration signed by Brazil and Argentina in 1988 provided for a parliamentary committee to follow up negotiations. The Asunción Treaty almost failed to include the JPC — it is not mentioned in the institutional structure, but in the "general provisions" at the very end. The purpose of this last-minute body was to accelerate the ratification of the Treaty in national chambers and to ensure this procedure in the future, considering that more parliamentary approvals would be necessary until the implementation of the common market. JPC approved its internal rules in 1991: it would be formed by sixteen deputies appointed by each national congress and meet twice a year. One of its statutory attributions was to develop actions required for the establishment of the Mercosur Parliament.

The Permanent Administrative Parliamentary Secretariat of Mercosur was established in 1997, following a demand of the European Commission, which asked for a contact body to negotiate the cooperation project in 1996. In spite of its small staff, the Secretariat centralized JPC's structure in Montevideo and provided administrative support to the meetings. In 1999, it helped to establish the first agenda for the institutionalization of a Parliament in Mercosur.6 The agreement with the EU was implemented in 2000 and offered JPC a budget of € 917,175 over three years, which substantially changed the Secretariat's work dynamics. Based on the Secretariat's 1999 plan, JPC started to discuss more concretely the idea of creating a parliament. The Secretariat organized seminars bringing together deputies, staffers from national committees and academics,7 which provided experience-sharing opportunities and theoretical grounding for deputies to agree on new actions regarding the subject.8 In 2003, the Argentinian and Brazilian sections presented the first written proposals concerning the Parliament. The following year, JPC arrived at an initial version of the project for a Constitutive Protocol, already mentioned in the Mercosur Work Program 2004-2006.9

Committee members expected the approval of the draft Protocol in the Mercosur summit of Ouro Preto in December 2004, which was to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Ouro Preto Protocol. But the presidents decided JPC should pursue the debates on the subject. A team formed by specialists, civil servants of Mercosur and national parliaments and representatives of political parties was thus formed to improve the proposal in technical terms, in order to support further political discussions. The Constitutive Protocol of the Mercosur Parliament was finally approved by the Council in December 2005.10 During 2006, it was gradually ratified by each member-state. The new assembly was officially opened in December 2006 and began its working sessions in May 2007. It represents the peoples of Mercosur and should be formed by directly elected representatives. The next section sets out the main features of Parlasur by means of a comparative analysis of the process of parliamentary institutionalization in Mercosur and the European Union.

Parliamentary Institutionalization in Mercosur and the European Union

This section proposes a linkage between institutionalization theory and the realities of the European and Mercosur Parliaments. After identifying and organizing the criteria for parliamentary institutionalization, it is time to apply the framework to the concrete experience of Parlasur. The EP is presented here as an external element intended to serve as a parameter to understand the parliamentary path in Mercosur, even though it has participated actively, along with the European Commission, in the creation of Parlasur (Dri 2010). Although the real world is not likely to follow the exact conditions foreseen by political theory, the use of an ideal platform in the study of Parlasur has the advantage of supplying objective standards to measure its institutional achievements, limitations and the place it deserves in legislative studies. The following analysis is thus organized according to the criteria mentioned: autonomy, complexity, socialization and attributions.

Interdependence or dependence? The insignificant autonomy of the Parlasur

Institutional autonomy refers to the construction of organizational identity through space delimitation, membership identification and differentiation from other political and social organizations. Immersed in the political system, autonomous legislatures also demonstrate linkage to their environment. Interdependency vis-à-vis other institutions and citizens' demands are part of a free-standing parliament. If the European Parliament nowadays fits into all of these criteria, this was not the case in the beginning, which approximates the EP and the Parlasur.

Both institutions have a delimited symbolic space, although the Mercosur Parliament remains without its own seat. Temporarily, plenary sessions take place in the Edificio Mercosur in Montevideo, Uruguay, where the Parliament's technical and administrative structure is located. But the building cannot accommodate offices for the members of parliament or for permanent committees. The EP has three different workplaces, established officially only in 1992 (Brussels, Strasbourg and Luxembourg, the latter only for certain administrative services), which is costly and time-consuming. In terms of juridical structure, there is no formal provision regarding the legal personality of the Parlasur.

Having power over the High Authority ensured some autonomy to the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). In general, the rapport between the two institutions was good, and a sort of alliance developed in order to improve the supranational spirit of the ECSC. On the other hand, the absence of control power over the Council of Ministers and the nomination of deputies among national parliamentarians limited the Assembly's activities and made it dependent on national governments and parliaments. Especially after the direct elections of 1979, the European Parliament improved its organic, institutional and political independence (Costa 2001, 37). The possibility of accumulating the European mandate and national functions continued in some countries, but the autonomy of most of the deputies in relation to national chambers strengthened the identity and the prestige of the EP. The suffrage also allowed an enhancement of the EP's direct relations with the Council and symbolically reaffirmed the roles already achieved by the Parliament, which reinforced institutional and political equilibrium within the Community. With the implementation of co-decision ("ordinary legislative procedure", according to the Lisbon Treaty), the Parliament is responsible, along with the Council and the Commission, for most legislative decisions. There is thus evidence that the empowerment of the EP brings with it autonomy and interdependence to the European institutional framework. Indeed, the design of the EU's political system demands from actors that they listen to their counterparts in the other institutions (Peterson and Shackleton 2002, 350). The Parliament is not only interlinked with other European institutions but also with citizens' associations and other interest groups in a highly institutionalized manner. As the members of the European Parliament (MEPs) cannot count solely on their elected mandate to legitimize their action, they try to compensate a problematic representation by invoking citizens' expectations and being attentive to the demands of social organizations and lobby groups (Costa 2006, 17).

The representatives of the Mercosur Parliament are not easily identifiable as MEPs are today. They belong to national chambers (except for Paraguay) and this is considered their main arena. Besides, Parlasur is dependent not only on national parliaments but also on national governments, due to the coalitional presidential system typical of the region (Santos 2003; Malamud 2003). Direct elections may partially change this situation, chiefly because the Constitutive Protocol forbids the simultaneous holding of two terms of office. Parlasur autonomy depends on full-time Mercosur deputies, so that they can start thinking with a regional perspective.

The limited interdependency of Parlasur regarding Mercosur decision-making bodies does not contribute to its institutional consolidation. The Parliament may request information from the CMC and other bodies, but this mechanism has only been used twice and the CMC has not officially responded.11 Another situation concerning the accountability function of Parlasur illustrates the imbalance in its relations with Mercosur head institutions. The Constitutive Protocol, as well as the Rules of Procedure, provides that the Mercosur temporary presidency12 shall attend Parliament each beginning and end of semester to present either the work programme or the activities developed. After the presentation of the Paraguayan minister of foreign affairs in 2007,13 parliamentarians have started a debate about the possibility of asking questions and requesting more detailed explanations from the invited authority. The implicit majority position was that the report should not be discussed with the minister because a potential embarrassing situation could make governmental authorities refuse to attend the Parliament in future, meaning that governments could legitimately go against a regional rule if the assembly asks for too much. Given that the Protocol fails to mention this point, parliamentarians could have interpreted it in order to enhance their faculties. Nonetheless, they chose to do exactly the opposite, giving up on discussing relevant themes presented in the account, such as projects for structural founds, limits to the free circulation of products, the creation of the Mercosur Social Institute and the new commercial agreements between Mercosur and countries outside the bloc. After the following minister's speech, this time from Uruguay three months later, no comments were made.14 A year later, during the Brazilian presidency, the speaker of Parlasur talked to the Brazilian minister of foreign affairs before the plenary session and the latter agreed to answer questions from parliamentarians.15 This represented a turning point for ministerial speeches at Parlasur: no other authority could refuse to have discussions after that.

Deputies' general passive behaviour reveals the imbalance between the Common Market Council and the Parlasur, and reflects a reproduction of the logic of national politics: legislatures wait for government initiatives and search for the required majority to approve them, instead of making proposals and pressuring the executive. Other evidence of this institutional disparity includes the absence of a record of the Mercosur Secretariat's budget report, which should be sent annually to the Parliament. In addition, temporary presidencies have not returned at the end of the semester for an evaluation of their programme, as the Constitutive Protocol establishes, nor has Parliament demanded this. On the one hand, this may be a normal situation during a period of institutional structuring; on the other, it represents the institutional weakness of the Parliament and its dependence with regard to the executive bodies of Mercosur.

Relations with non-decision-making Mercosur bodies are slightly different. Institutions like the Economic and Social Consultative Forum consider the Parliament an ally in achieving more influence over regional decisions. In 2007, the Parliament signed an institutional agreement with ESCF. According to the document, the two institutions are to meet at least once a semester in order to exchange information and impressions about the integration process.16 The Forum can also offer reports and opinions that are considered by the Parliament, whether or not requested by it. This commitment aims to reinforce and formalize the rapport that existed between the ESCF and JPC, and to increase the possibilities of the Forum intervening in Mercosur policy-making.

Institutions working with integration issues without being part of the Mercosur structure also expect the Parliament to contribute to their representativeness in the regional decision-making process. Mercociudades, which represent local governments,

[...] has always defended, promoted and asked for a Parliament in Mercosur, as a means of enhancing and democratizing integration. Mercociudades has agreed on the creation of Parlasur and firmly expects the Parliament to succeed in its role of deepening and decentralizing the integration process in order to limit power concentration and stimulate transparency in Mercosur, [...] [According to a member of staff.17].

In 2009, the Parliament signed a cooperation agreement with Programa Mercosur Social y Solidario (PMSS), formed by non-governmental associations from Mercosur countries.18 The agreement oversees the exchange of documents and information and organization of joint courses and seminars. In spite of the feeble functions of the Parliament, it is perceived as a sort of political platform for different types of demands from several regional actors. Clearly, the potential rather than the present role of Parlasur is being considered. Besides, this shows a latent wish on the part of Mercosur institutions and economic and social forces to be listened to by governments.

Another example of Parlasur external institutional contacts consists in the negotiations with a view to the Unasur Parliament.19 Some Mercosur representatives have participated in meetings with the Andean Parliament to discuss possibilities of partnership between the two institutions20 and the formation of a "South American parliamentary space".21 Directly negotiating with its international counterparts and the intention of taking part in major continental issues denotes Parlasur's autonomy. This position is also seen in the participation in the Euro-Latin American Parliamentary Assembly (Eurolat),22 which conducts periodic meetings in Europe and Latin America.

The limited autonomy of Parlasur is also related to its social meaning. Until now, most citizens are clearly unaware of the existence of the Parliament, in spite of recent initiatives in this respect.23 This fact can be explained by three main reasons: ignorance about Mercosur in general, Parlasur's still incipient web-oriented publicity initiatives and the lack of press information about regional integration issues. The construction of a social imagination about the assembly may begin when it displays an interest in citizens' demands, putting into practice mechanisms to deliberate on their bases. The Constitutive Protocol and the Rules of Procedure provide that the Parliament is to organize public hearings with civil society and business organizations, and to receive petitions from any person or organisation related to acts and omissions of Mercosur bodies. Some committees have discussed issues of social relevance to the region, like foot-and-mouth disease and children's and women's rights, but their conclusions or propositions are still restricted in terms of public reach and effectiveness in everyday life.

Parlasur's "independence and autonomy" affirmed by the Constitutive Protocol may be achieved when it starts acting according to its own values and interests towards integration and specifies its particular intervention field, that is to say, when the institution becomes relatively well-bounded and interdependent with other Mercosur bodies. This is not the current general situation: executive branches keep defining integration policies without consulting parliamentarians. For now, the autonomy of the Mercosur Parliament is insignificant and less important than the autonomy of the Common Assembly. The absence of headquarters, the dependence on national parliaments and executives and the distance from civil society are characteristics of both institutions, but the European assembly could control the High Authority and therefore developed relative horizontal rapports with it. The project of direct elections is an advantage for Parlasur, but the traditional fragility of South American legislative chambers may extend to the regional level, which would continue to limit the differentiation and the interdependence of the Mercosur Parliament vis-à-vis other institutions of the bloc.

From parliamentary organization to institutional complexity

Complexity refers to functional differentiation and specification within the institution, which derives from a relative hierarchical organization, the structuring of units and sub-units and the "routinization" of procedures. It comprehends the universalization processes of unification and objectivization (standardization/formality). An institutionalized parliament should consist of a coherent and impersonal collectivity whose rules are clear and public and apply equally to all actors. The production of its own values, the definition of reproduction mechanisms (recruitment and socialization), the insertion of formal regulations in a hierarchical system (Delpeuch and Vigour 2006, 141-2), regularity of meetings and the existence of bodies which are able to speak for the institution are some of the main required characteristics. In the case of a regional parliament, direct elections and representation proportional to the size of the states in question are also important indicators. The Mercosur Parliament seems to be heading in this direction, while its European counterpart has already consolidated these practices.

The European Parliament displays a highly complex internal organization, improved over the years. The Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community had six specialized committees, created to follow the High Authority's activities, although the censure motion was never used. According to the ECSC Treaty, it could set its own Rules of Procedure. In 1953, political groups were officially recognized and in 1958 the European Parliamentary Assembly created thirteen permanent committees. Nowadays, seven political groups, more than twenty committees and thirty-four delegations structure work within the Parliament, assisted by a Secretariat. If political groups are compared to the Parliament's lifeblood, the committees are its legislative backbone (Westlake 1994, 191). The Bureau is the regulatory body, consisting of the president, the fourteen vice-presidents and the quaestors, elected for two and a half years. The bodies responsible for the broad political direction are the Conference of Presidents, formed by the EP's president and the chairs of the political groups, and in a smaller measure, the Conference of Committee and Delegation Chairs. For its part, the Parlasur framework is relatively simple. The Rules of Procedure, drawn up mainly by the Brazilian representation staff, were adopted in 2007 after a semester of difficult negotiations. Differently from the EP, which transformed the right to adopt its own rules into an instrument of interpretation of the treaties in order to extend its power and influence (Judge and Earnshaw 2003, 196-7), current Parlasur Rules detail some Constitutive Protocol previsions without running the risk of escaping its framework.

In Parlasur, the Bureau is made up of a president and one vice-president from each member-state elected for a two-year period, without the possibility of reelection.24 Until the first general elections, however, the president is replaced every six months following the Mercosur temporary presidency,25 which entails less coherence to the annual session. Besides administrative tasks, the Bureau defines the subjects to be dealt with in plenary sessions and sets the agenda in conjunction with the coordinators of political groups.26 The Parliament has ten permanent committees: 1) juridical and institutional issues; 2) economic, financial, commercial, fiscal and monetary issues; 3) international, interregional and strategic issues; 4) education, culture, science, technology and sports; 5) labour, employment policies, social security and social economy; 6) sustainable regional development, territorial organization, home, health, environment and tourism; 7) citizenship and human rights; 8) security and defence; 9) infrastructure, transport, energy sources, agriculture, cattle-rearing and fishing; 10) budget and internal issues.27 The Bureau establishes the committees' makeup in the beginning of each year. Temporary and special committees can also be formed to deal with specific issues, as well as external delegations to represent the assembly in international organisations and events. Four temporary committees have been organized so far, mainly to investigate transnational problems regarding sanitary questions and human rights. According to the Rules, committees should reflect political groups' relative strength,28 but Parliament has adopted national criteria, for now. The predominance of the national logic within Parlasur also comes through in other organizational aspects: Bureau structuring, geographical positioning of deputies during sessions and organization of debates, when a parliamentarian often speaks in the name of his/her national delegation. This constitutes a substantive difference in relation to the EP, whose members decided from the very beginning to organize their work along lines of ideological affinity.

However, daily parliamentary work has been displaying exceptions to this logic. One of them is the formation of political groups. According to the Rules, they can be formed by five parliamentarians, if they belong to more than one member-state, or by ten per cent of the total number of deputies if they have the same nationality.29 This rule facilitates the maintenance of the national organization within the assembly but also allows regional arrangements, which is totally new in Mercosur. Informal meetings and discussions within the two main political forces — the "progressive" and the conservative or social-democrat — have taken place since the launch of the Parliament. The Progressive Group was formalized in November 2009, bringing together members of left-wing tendencies from all the countries, including Venezuela.30 Before that, in August 2007, a group with a national character had been formalized: the Uruguayan National Party Group.31

The Rules establish that Mercosur parliamentarians will be elected by citizens through direct, secret and universal suffrage according to a proportional criterion related to member-states' population.32 However, during the first legislature, each national congress has nominated the same number of representatives (eighteen, according to the Constitutive Protocol, and eight for states during processes of adhesion). Paraguay was an exception: direct elections for Parlasur were organized simultaneously with the presidential elections in April 2008. This country has thus unilaterally fixed its representation on eighteen deputies. The other national delegations disapproved of this, for they considered eighteen a high initial number, whilst Paraguayan representatives had always refused to discuss proportionality within Parlasur. In 2009, when some parliamentarians had already given up on the negotiation, the Parliament finally came to an agreement on the national representation criteria. This agreement has two dimensions, one parliamentary and one judicial. Firstly, the Parliament recommends that the Common Market Council approve a relative "citizenship representation", which implies 75 deputies for Brazil, 43 for Argentina, 18 for Uruguay, 18 for Paraguay and 31 for Venezuela when it completes its process of adhesion to Mercosur, as well as requesting more powers and political influence for the institution. Secondly, deputies demand the creation of a supranational court of justice in Mercosur and, transitorily, more competences to the existing Permanent Revision Court, which was the condition for Paraguay to accept proportionality. This recommendation has not yet been appreciated by the CMC. In the European case, the 78 deputies of the Assembly of the ECSC were designated proportionally to national populations but considering a favourable balance to the smaller states (Germany 18, France 18, Italy 18, Belgium 10, Netherlands 10 and Luxembourg 4), which remains a feature of the European Parliament. Direct elections only happened in 1979, almost thirty years after the creation of the assembly. Aware as it is of the European experience, the Mercosur Parliament is certainly intending to move faster through certain phases.

The Common Assembly of the ECSC used to meet once a year, in the second week of May, to analyse the High Authority's report. Only the Council and the High Authority could call extraordinary sessions. The European Parliament nowadays sits once a month in plenary sessions. Similarly, the Mercosur Parliament ordinary sessions take place monthly from 15 February to 15 December.33 The CMC, the Bureau or 25% of parliamentarians can decide on extraordinary sessions.34 The Bureau also meets once a month, usually two weeks before the plenary session. Committee meetings are less regular, due to the lack of structure to organize the agendas and the low priority of regional integration to national deputies. All meetings should be public unless they are declared closed to the public, which requires an absolute majority vote.35 In spite of this, Bureau meetings are not open, and its minutes and decisions have not been made publicly available.

Parlasur has four secretariats (parliamentarian; administrative; institutional relations and social communication; and international relations and integration), corresponding to the number of Mercosur member-states, divided into four small rooms at the Edificio Mercosur in Montevideo. The number of staff has been on the increase since the establishment of the assembly, reaching some thirty-five at present. The Parliament makes up for its limited permanent structure with national delegation officials, who come to Montevideo during plenary sessions and develop an important part of the work. Nevertheless, this precariousness affects the rhythm and the quality of activities. For instance, if committees rarely meet due to their lack of staff and organization, discussions and decisions about certain topics may not progress in plenary sessions.

Members of staff are recommended by national parties, governments or congresses, although the Constitutive Protocol determines the holding of open external competitions among citizens of member-states to make up the technical and administrative staff,36 like in the European Parliament. The current budget — about 1 million dollars per year — depends on equal contributions from states, but its execution is not available on the website as indicated in the Rules of Procedure,37 January 2007 excepted. The Parliament should also publish an official journal with its rules, propositions and meetings reports.38 However, a significant part of the legislation approved by Parlasur is expressly not public, as well as the proceedings of Bureau and Committee meetings, even though the Constitutive Protocol and the Rules of Procedure affirm the "most complete transparency" of Parlasur activities. Even if one considers the website a real advance concerning parliamentary communication in Mercosur, its general information is limited and the diffusion of the site itself is not substantial, even among regional institutions. This lack of transparency regarding staff appointments and Parliament's resources and decisions clearly restricts the institutionalization of the assembly, introducing a personalist/particularist logic that prevents the consolidation of democratic principles within an institution that was supposed to democratize the whole integration structure.

In terms of complexity, Parlasur and the EP in the 1950s strongly resemble each other. Both institutions have provision for their own Rules of Procedure, Bureau, Secretariat, committees and political groups. Nonetheless, an important difference is the early organization of political affinities in Europe and the maintenance of the national logic in the first years of the Mercosur Parliament. Another element that limits the satisfactory complexity level of the assembly is the incipient and precarious structuring of the secretariats and committees. In spite of this, the introduction of proportionality and the provision of direct elections are elements that government beyond the traditional intergovernmental logic of Mercosur and introduce indications of deeper institutionalization in the Parliament.

Socialization on the increase

If the development of the attributes mentioned above — autonomy and complexity — is part of legislatures' establishment, they are not sufficient to characterize a consolidated institution.

For a parliament it is a matter of coming to embody values shared in some significant degree by the society at large. Moreover, a clear line cannot be drawn between the institution and its members: it is how they behave within the normative framework set by the institution that determines its character and perhaps its chances of survival (Johnson 1995, 609).

This process refers to parliamentary socialization, which can take forms such as, a) adaptation to the institutional role, b) increased institutional support and c) ideological convergence (Navarro 2009, 195-6). In terms of regional integration, it means the progressive strengthening of communitarian convictions among the deputies is an important aspect of the socialization process, but not the only one. The acquisition of new skills and understandings, related to the traditions and procedures of an assembly, and the shape of preferences, which tend to harmonize and moderate political demands and policy goals, are aspects of the parliamentarian experience that cannot be neglected. They result from interpersonal relations among deputies: the feeling of belonging to a group and the wish to share values and knowledge increase in line with the quantity and quality of connections and the level of mutual trust and sympathy.

Much research remains to be carried out on socialization in the European Parliament, but the idea that the EP accomplishes an "integration function" by socializing the members is widely accepted. Empirical information will confirm this hypothesis or not depending on the different variants of the socialization phenomenon. A survey data analysis, relating to the attitudes of members of the European Parliament between 1996 and 2000, showed that the experience in the EP does not socialize deputies into more pro-European attitudes (Scully 2005). The author concludes that there is little evidence that MEPs are more pro-integration than their national counterparts, and when this happens, it appears to be unrelated to deputies' length of service in the EP. In the same sense, an analysis of roll-call voting data from 1999 plenary sessions evince that MEPs do not become more inclined to support measures of closer integration as time passes (Scully 2005). Hence, the fact that the EP has constantly pushed for more European integration and for a more significant role in the institutional design (Costa 2001; Costa and Magnette 2003) cannot be explained by parliamentary socialization at the European level, but rather by national politics. MEPs belong to national parties, which, in general, have historically supported the integration process. Among them, euro-scepticism has been the exception.

MEPs are generally pro-integration for the same reasons that national MPs are: they are members, and representatives, of parties for whom such views are part of accepted, mainstream political opinion (Scully 2005, 142).

Deputies' interest in increasing their powers is also due to the EP's strategic importance. Since their arrival in Brussels, MEPs understand that institutional competition within the Union will leave them little space if they do not perform their role actively (Costa 2001, 66).

On the other hand, the institutional framework of the EP has a significant impact on members' behaviour, even if parliamentarians do not necessarily interiorize a common understanding of their role or converge in their attitudes (Navarro 2009, 234-5). It means there is parliamentary socialization on the European stage, but it can be temporary or strategic rather than permanent: deputies learn about the assembly's formal and informal rules, realize which are the most efficient procedures and patterns of behaviour, discover how to work with colleagues from different nationalities, acquire new professional skills and understanding of politics. This situation is reflected in the particular modes of political competition and conversion within the EP. Although political cleavages in the EP are structured according to right-wing/left-wing and integration/sovereignty positions (Hix 2001; Noury 2002), the deliberation process reveals a more complex logic. The absence of a European government, the complex nature of texts submitted to the assembly's appreciation and, more generally, the mobilization around the consensual and "non-political" objective of forming a "union", which characterized European construction, result in a relative fragility of the party phenomenon, fluidity of majority combinations and a consensus-building that surpasses traditional ideological divisions (Costa 2001, 328). Moreover, treaties force deputies to overcome their heterogeneity if they want to take part in the decision-making process. But these features are not necessarily related to ideological convergence among deputies: the inclination to vote with EP or group majority is not connected with seniority or previous political experience (Navarro 2009, 199).

Due to its brief existence and incipient activities, precise conclusions about socialization within the Mercosur Parliament are very limited. In general, adaptation to the institutional role seems to be on the rise among some deputies. "When I go to Mercosur, I am not a Brazilian deputy anymore, I am a Mercosur parliamentarian. We have to see things this way".39 If it is true that accommodation is more significant than assimilation in the EP, Parlasur faces the opposite situation. As the assembly is still young and procedures are being set out, rules are to be created more than to be followed. Each national delegation conceives of the parliament according to its own political culture and constitutional system. Moreover, each parliamentarian devises the assembly depending on his/her ideological orientation and general idea of Mercosur. During debates or negotiations, mention of rules and experiences from national contexts and attempts to import them to the regional ambit are not rare. For instance, a Paraguayan deputy insisted that his surprise at a certain statement in the Rules of Procedure be recorded, since it was considered "unusual, mainly to the Paraguayan delegation".40 In a process in which socialization creates political culture, this is quite a normal situation: creation never occurs without integration and maintenance of old values with the new (Dawson and Prewitt 1969, 27). But it is important to pay attention to the rigidity level of this sort of variable, which may influence the accommodation/assimilation balance in the Mercosur Parliament over the next few years, and consequently its degree of institutionalization.

The working languages are an advantage for Parlasur over the European Parliament. Spanish and Portuguese are the only dominant languages in the region. Although all documents are to be drawn up in both languages and parliamentary sessions have simultaneous interpretation, in general, parliamentarians understand each other without this mechanism. It facilitates deliberation within the assembly and informal contacts among deputies and assistants.

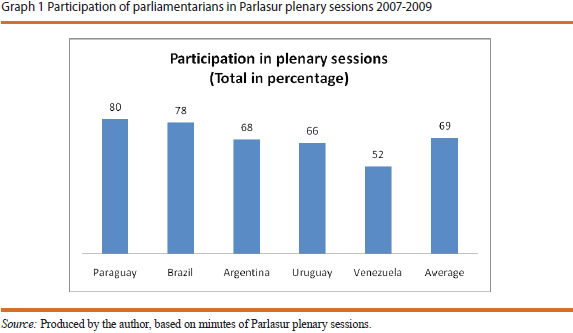

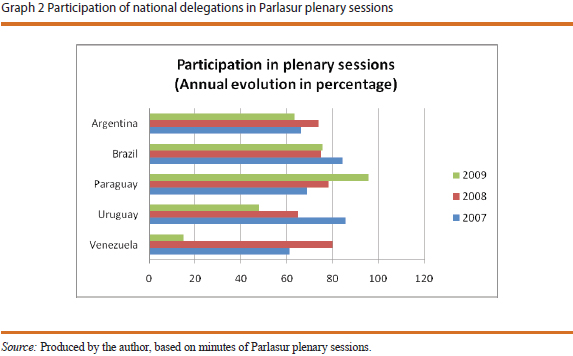

Simple participation in plenary sessions translates into a socialization benchmark if it means the recognition of an additional level where political life takes place. The three years studied (2007-2009) reveal a stable and relatively high attendance level in comparison with the last meetings of the Joint Parliamentary Committee. Paraguay displays the highest participation level, which has increased after its representatives were directly elected in 2008. Before that, Brazil used to have the most participative delegation. Uruguayan deputies are the least participative and their presence in meetings has been gradually decreasing, which is due to the feeble participation of National Party deputies and to the priority given to national issues over regional discussions, considering that they stay in Montevideo for Parlasur sessions. The Brazilian and Argentinian delegations display the stablest participation rates. (As for Venezuela, the current absence of voting rights helps explain the delegation's reduced presence.) The EP faced the opposite phenomenon: absenteeism has been a problem from the Parliament's earliest days. Deputies who had to travel the furthest, attended the least (Kapteyn, quoted in Westlake 1994, 102).

In terms of support for integration and ideological convergence, there is a clear and progressive movement towards recognizing the importance of regionalism itself and of the Parliament, although national agendas still guide deputies' actions and preferences. As one deputy puts it,

I have always been proud of Mercosur, I always thought this is an interesting way, even more when the Parliament was established, because it is no longer a strict commercial question, but it comes to deal with environmental, social issues.41

Until now, the procedure to appoint the regional parliamentarians was internal to each congress. The choice and arrangements to compose the representation in the Mercosur Parliament were analogous to the formation of other national parliamentary committees: membership was mostly self-selected and proportional to the weight of each political party. Just like in the beginning of the European Parliament, members of Parlasur were nominated according to some sort of interest in integration matters. Many of them were already involved in the JPC and participated in the negotiations that led to the emergence of the Parliament. But this "affinity" with integration is less important in Mercosur than it was in the European Union, where the Common Assembly of the ECSC developed an open militant federalism in favour of further steps towards integration (Westlake 1994, 11). With direct elections, the tendency is a reproduction of the European phenomenon: parties will select pro-integration candidates or politicians either retiring from national political life or wishing to start a career.

A movement seen since the start of Mercosur continued in the beginning of the Parliament's life: parliamentarians from the Left, from smaller countries and from border regions are, in general, more inclined to work actively for the integration process. But lately, interest in the new assembly has been growing among other groups of parliamentarians, especially among the most prestigious politicians of each national congress, among the right-wing and those who had not participated in regional experiences before. In the same sense, a certain bad reputation of the deputies who "go for tourism in Montevideo" is decreasing among their national counterparts, which means the relevance and the visibility of Parlasur are on the increase. When it comes to institutional support, the majority of members and staff recognize the importance of the integration process and the need for a regional political arena.

The ones who are here, many are from the very beginning of all this, then we are pretty much impregnated by what is the work in the Parliament, and new people that join us also feel involved with the team work. [...] In general, the ones who work here have this idea [the belief on integration, the need to deepen Mercosur]; [...] comparing to other Mercosur institutions, I think here in the Parliament we have more people with a passion for integration.42

For now, the only exception is the Uruguayan National Party, whose representatives opposed the Parlasur's creation at the outset, believing it would affect Uruguayan sovereignty.

Political groups are another relevant indicator of parliamentary socialization. Initially, members of Parlasur have registered two groups composed of members of only one member state: National Party and "Frente Amplio", both from Uruguay, the country with the strongest party tradition in Mercosur. But that strategy has been replaced by a different perspective on the organization of political action in Parlasur: the formation of transnational ideological forces. The Progressive Group was the first to be established by centrist and left-wing parliamentarians who actually guided the creation of the assembly and have always had the majority of seats in the Bureau. Informal meetings generally take place once a month before the plenary session in Montevideo. Ideological identification and mutual trust can be considered high among its members. The conservative group is not yet very well organized due to a lack of ideological consensus among the right-wing parties of the region. Another point is the analogy with the European People's Party: a segment of the Brazilian Right considers itself more social democratic and would not like to be compared with European Christian democrats in inter-parliamentary forums. But negotiations are in progress and, when formalized, this group should have a majority of seats in Parlasur.

This ideological movement is more important to some delegations than to others. Brazil and Paraguay display a high level of cohesion inside the delegation due to the traditional weakness of national political parties and to the feeling that there are national interests to be protected. Brazilian deputies support each other in Parlasur negotiations even if in the internal arena they take part in tough disputes. In the case of Paraguay, almost all the representation comes from right-wing forces, which contributes to the unification of positions. On the other side, the Uruguayan and Argentinian delegations are less united due to the strength of national parties in the first case and to a particular political culture in the second. The relative maintenance of the national logic at the same time as ideological groups are being established can reflect either the current transition and institutionalization period of Parlasur or the classic personal-oriented politics still present in Latin American culture. The socialization effects should be slightly divergent from one hypothesis to the other.

The coherence mentioned by Huntington, March and Olsen is also related to socialization. The more socialized an institution is, the more members will agree about its functions and objectives, and the decision-making process will be less troubling. In the case of the Mercosur Parliament, records show a limited consensus about the real role of the assembly. The few instruments discussed by parliamentarians with this objective reveal the usual agreements on democratic liberties, human rights and the consultative role of the Parliament, even if the necessity of reinforcing political integration is generally stressed. This was the case of a paradigmatic debate about the Parliament's functions in the integration process in 2007.43 Points of divergence emerged, although all speeches agreed on the fundamental role of Parlasur regarding the necessity of surpassing the commercial integration and reinforcing Mercosur mechanisms in order to reach social inclusion, sustainable development and international influence. It means that although the assembly still lacks a clear project, the deliberation itself reflects the fact that deputies accept debating the functions and the mechanisms of the Parliament. Consequently, they recognize the legitimacy of the institution and the principle of a supranational and reflexive deliberation, which may have significant influence on the other powers of the Mercosur Parliament (Costa 2001, 483).

The socialization of actors within Parlasur remains limited but has been increasing since the establishment of the institution. Limitations have to do with the temporary combination of national and regional terms of office and with Mercosur's general lack of visibility and information on its acts and role. Alternatively, the high participation in meetings, the incipient pro-integration propositions of some parliamentarians and the constitution of ideological groups denote a latent socialization potential. But as the European experience shows, this does not necessarily mean a socialization of consequences that surpass the ambit of the Parliament. In Parlasur, the general limited socialization is related to the other institutionalization phases: in order to develop an integrative function of its members, an institution has to be autonomous, complex, display universal values and rules and have certain policy-making powers. The weak structuring of the Mercosur Parliament does not make it politically attractive to deputies and consequently does not facilitate their socialization. Therefore, a transitory and strategic internalization of the rules of the game and some kind of identification with other members would already reflect a different level of parliamentary institutionalization in Mercosur.

Attributions, not competences

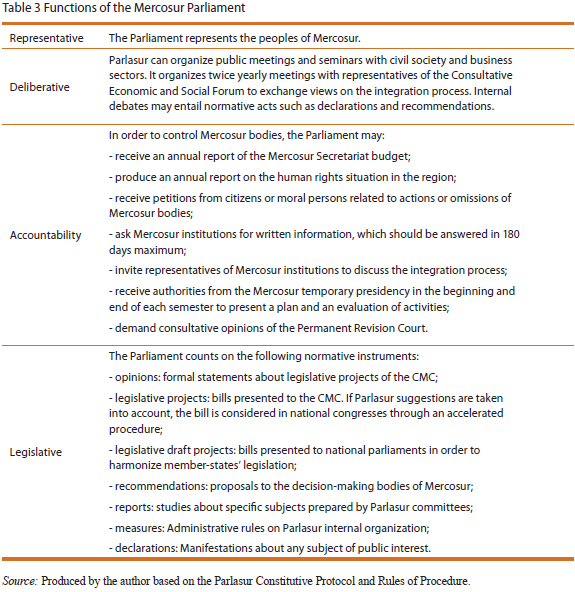

"Attributions" are understood in this paper as the development of typical parliamentary functions combined with material competences. In national democratic political systems, parliaments usually perform representative, deliberative and accountability functions, besides legislating on a broad range of social, economic, cultural and political issues. However, this classic concept cannot be directly applied to regional organizations. The European Parliament is responsible for all parliamentary functions at the supranational level, but its control and legislative powers are limited not only by the communitarian competences but also within them. As an entirely intergovernmental system, Mercosur does not have exclusive areas or sectors of competence, which applies to the Parliament by extension. It means that all subjects can be discussed or regulated, but the final decision belongs to national institutions. In addition, the Parliament was not conceived as part of the decision-making structure of Mercosur. Therefore, the Parlasur does have some functions, but these are restricted both by the lack of supranational prerogatives and by the consultative status given to the assembly.

The permanent reinforcement of the European Parliament's powers is a major feature in the history of European construction. In 1952, the Common Assembly had only deliberative and relative accountability functions. The faculty of adopting declarative resolutions on the missions of the Community and the abstract possibility of provoking the dismissal of members of the High Authority entailed a gradual affirmation of the assembly vis-à-vis other institutions. The supranational management of coal and steel resources was the basis of the need for a body to control the executive branch, which configures a fundamental difference from the Mercosur experience. In 1957, the European Parliamentary Assembly gained consultative powers regarding the budget and legislation. From 1970 on, following the new model of financing proposed by the Commission, the Assembly had the final word on non-obligatory expenses and in 1975 it was accorded the possibility of rejecting the whole budget. From 1979 on, the directly elected deputies started employing a double strategy of specific unilateral initiatives and broad formal demands on the extension of their powers (Costa 2001, 38). In 1980, for instance, the Parliament began approving commissioners nominated by the Council through its deliberation capacity. Nowadays, the European Parliament has extensive attributions regarding representativeness, deliberation, accountability and legislation. The most common and influential legislative procedure, co-decision, assures the EP the final decision, along with the Council, on more than forty communitarian areas. Concerning appointment faculties, the EP can influence the investiture of members of the Commission, the Court of Auditors, the Central Bank and the European Ombudsman. In the same direction, the institution has several means of controlling executive activities: oral and written questions, reports, petitions, temporary inquiry committees, sanction measures and the right to appeal before the Court of Justice.

The Constitutive Protocol of the Mercosur Parliament establishes the following functions: (see Table 3).

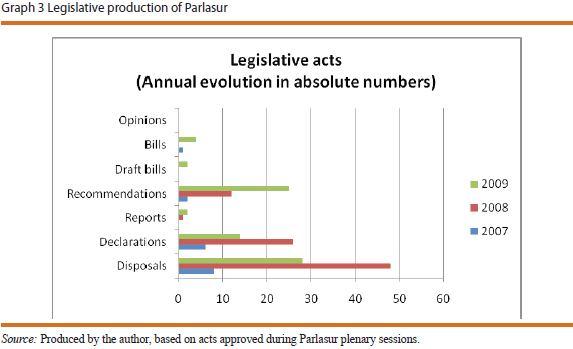

In absolute numbers, the Parliament has adopted more than 170 normative acts since 2007. The average of six instruments per plenary session is much higher than the legislative production of the Joint Parliamentary Committee, and has been increasing: from 1.5 acts in 2007 to 7.5 in 2009. However, the most common acts — measures, declarations and recommendations — seem to be the least efficient way to intervene in the Mercosur's directions. Bills and opinions on CMC projects obviously display a more important influence potential, but were rarely discussed by parliamentarians, as shown by Graph 3. Nevertheless, the decrease in the number of declarations and the progressive increase in the number of recommendations approved indicate a gradual shift on the legislative behaviour of the assembly. Also, the four bills presented to CMC and the two draft bills sent to national assemblies in 2009 constitute new initiatives deriving from the rationalization of parliamentary work and the development of knowledge of the instruments available on parliamentarians' part.

In terms of contents, most of the norms adopted consist in administrative determinations and rhetorical manifestations about subjects relating predominantly to disputes between national political forces or to international events. Debates about integration issues or about the role and the objectives of the Parliament itself are not frequent and have rarely become rules. In addition, parliamentary deliberation is usually disconnected from the topics dealt with at CMG or CMC ambits, which entails a low interest level by decision-making bodies in subjects discussed by the Parliament. Until now, the Council has not considered any of the recommendations or bills formulated by the Parlasur. Besides Brazil, no other national congress has regulated the fast track procedure for Mercosur rules relying on a favourable opinion from the Parliament, which prevents the building of an important item of bargaining power for the assembly. The annual report on human rights, the only substantive faculty of the Parliament, was first published in 2009. Except for the visits of foreign affairs ministers once a semester and a few information requests to the CMC, no other accountability functions are being carried out. Public meetings and seminars are organized according to parliamentarians' agendas and interests, but the lack of publicity on their objectives and results does not motivate social participation. This scenario reveals the fragile degree of formality of Parlasur actions, and limits the construction of an institutional project.