My SciELO

Brazilian Political Science Review (Online)

On-line version ISSN 1981-3821

Braz. political sci. rev. (Online) vol.5 no.se Rio de Janeiro 2010

Judicialization of health policy in the definition of access to public goods: individual rights versus collective rights*

Telma Maria Gonçalves MenicucciI; José Angelo MachadoI

IFederal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Brazil

Replicated from Brazilian Political Science Review (Online), Rio de Janeiro, v.4, n.1, 2010.

ABSTRACT

The article analyses a form of judicialization of public policies in the health field. It has as its object lawsuits initiated against Belo Horizonte Municipality arguing for the provision of services or the acquisition of inputs not obtained in the public system via institutional access routes. The argument is that the individualized quest for the guarantee of the right to healthcare via the judicial path is a form of reproduction of the tensions produced in democratic societies between the social and the individual conceptions of citizenship. By ensuring access to goods by means of individual suits, the Judiciary interferes in the making of public choices taken on by public-sector managers, thus regulating opportunities for consumption according to a concentrating logic. And so the assertion of a constitutional right superposes the political right of the majority, represented by the Executive, to make choices as to the goods that are the object of public policies, with a relatively significant financial and budgetary impact.

Keywords: Judicialization of health; Individual rights; Collective rights; Public choices.

Introduction

One of the controversial debates in the field of public policy is related to what has been called the "judicialization of politics", referring generally to a supposed influence of the Judiciary over political decisions, taking on roles that should be exercised by the Executive and the Legislative. Such influence might be through the use of judicial procedures for resolving political conflicts, which include those related to public policies developed or implemented under the Executive and Legislative branches, which would eventually characterize a transfer of decision-making power to the Judiciary.

However, whereas this debate has become more intense, there is neither consensus on the term itself, nor on the actual reach of the Judiciary's influence on politics, when the expression takes on this general meaning. The debate is divided, also, between the positive view about the effects of the actions of the Judiciary, as the guarantor of rights in democratic societies, and a negative view, that sees it creating an imbalance between the branches of government at the expense of majority institutions and, therefore, of democracy.

With regard to public policies, the Judiciary's intervention, despite its important role as the body that guarantees constitutional rights, has been changing the initial intention (the distribution of goods and services) and affected many areas, including healthcare. In this sector, such interference has ensured services and benefits for certain individuals by means of the granting of a growing number of requests, which has been justified by the constitutional precept that "health is a right for all and a duty of the State" (Brasil 2006).

According to the current viewpoint of managers in this area, the systematic intervention of judicial measures in ensuring access to medication and services that the public health system does not provide for all citizens - including for reasons related to their efficacy, cost-effectiveness or economic factors - has disrupted the planning and programming of health activities that are provided by the public system (Single Health System (SUS)). In such circumstances, public managers find themselves constrained when implementing plans and programmes because they have to fulfil judicial decisions that allegedly consume much of the sector's budget, which is historically considered insufficient, both by international standards and for compliance with constitutional measures.

However, beyond affecting the administrative and financial organization, the Judiciary's interventions interfere in public choices defined in the political sphere, particularly in processes of implementation of policies or decisions taken by the Executive1.

This problem has not been analysed thoroughly from a theoretical and analytical point of view. The political debate regarding the topic in the health ambit has gained weight, and only recently been the subject of more systematic research that can produce consistent interpretations or generalizations about the nature and scope of the Judiciary's actions.

In general, and specifically in the health field, the challenge is to identify the real political influence of the Judiciary, and to discover the manner, extent and intensity of this influence and its effect on the direction of ongoing public policies.

This study systematizes research findings on a particular form of judicialization of the implementation of public policies in the health field, especially regarding the distribution of public goods, be they inputs or medical procedures. The purpose was to measure and identify the nature of the problem using the case study of Belo Horizonte. The objects of analysis were lawsuits filed against the Municipality or against the Municipal Health Department, which sought the service provision or the purchase of certain inputs that were not obtained or not guaranteed in a timely manner by the public system through institutional channels of access.

We start from two related hypotheses. The first considers that the individualized quest for the affirmation of the right to health by way of lawsuits is a form of reproduction of the tensions produced in democratic societies between a social vision, based on principles of distributive justice and solidarity, and an individual conception of citizenship, especially with regard to conflicting demands of individual and collective interests. On the one hand, some citizens individually seek the realization of interests based on the social right to health, which is not granted by the executive sphere. On the other hand, judges, by considering the right to health as a fundamental constitutional right, do not take into account the context of government decisions, but assume an abstract and individual concept of this right, which ends up precluding the achievement of such a right from the collective point of view. The second hypothesis was that, by privileging the guarantee of access to goods that were requested through individual legal action, the Judiciary directly interferes in the accomplishment of public choices that were made by the public health manager, regulating consumption opportunities according to a concentrating logic.

Two methods were used in order to answer the questions raised by the two abovementioned hypotheses. The first was a survey of the archives of the legal team of the Belo Horizonte Municipal Health Department, examining the files of individual lawsuits filed against the municipal government between 1995 and 20092.

The second was an analysis of the financial aspects related to the execution of such legal actions. The data were provided by the Belo Horizonte Municipal Health Fund (FMS/BH) for the years 2007, 2008 and 2009, the only years available.

The text is structured in three sections. In the first section, we formulate the central issue around which this study is organized. We start by verifying that current State jurisdiction has expanded, especially owing to the phenomenon of multiplication of social rights, arriving at conflicts concerning the delimitation of boundaries between the branches of government present in decisions regarding social policies since the 1988 Constitution, from the point of view of the judicialization of politics. In the second section, the research results are presented. We start with an analysis of lawsuits against Belo Horizonte Municipality or the Municipal Health Department, and then analyse the costs of lawsuits and their possible distributional effects. The third and final section presents some considerations based on the results produced.

Judicialization and Expansion of Rights

In Cidadania, classe social e status, when proposing the distinction between civil, political and social rights, Marshall (1967) describes the processes of geographical integration and functional separation that shaped the institutional systems required for processing each of them. In this context, the place of the Judiciary is unequivocal: it is bound with the definition and defence of civil rights, which this author believes were consolidated in eighteenth century England, mentioning Habeas corpus, the Tolerant Act and the abolition of press censorship. Gradually other individual rights were added, with their effects simultaneously extended to all adult members of the community. They were, therefore, universal rights, the subject of which is the abstract individual regardless of differences in concrete ways of being. Everyone becomes equal before the law and has equal rights3.

Notwithstanding the theoretical and methodological problems attributed in the Social Science field to this author's work, we take it here as allusive to a state prior to the contemporary phenomenon of the multiplication of rights (Bobbio 2004). This phenomenon intensified in the 20th century after the acknowledgement that the collective ownership of rights in the legal field, especially in the absorption of labour disputes in various contemporary legal orders, is directly related to the expansion of the Welfare State. In the context of this expansion, collective rights did not embrace only workers but citizens in general, whatever their position in the production structure. But the new rights and guarantees did not necessarily treat the citizen as a generic being: in most cases they referred to collective new subjects, distancing legal systems from the old liberal assumptions based on the relationship between the individual and the State (Sorj 2004).

In this respect, Bobbio (2004) draws attention to three dimensions of the multiplication of rights: the increase in the number of goods worthy of guardianship (political and social rights that demand an active position of the State); the extension of ownership of rights to subjects other than man (family, ethnic minorities etc); and the diversification of status that is due to the perception of man regarding specific or concrete ways of being in society (children, the elderly, the sick etc).

The multiplication of rights has, however, been accompanied by another contemporary phenomenon: the expanding scope of the Judiciary, which gradually begins to compete with other public authorities in the handling of political and social conflicts. For writers such as Sorj (2004), the two phenomena have a close relationship: the multiplication of social cleavages, related to the formation of new identities and points of interest under the impact of the decline in polarization based on labour conflicts has not found a corresponding matrix to voice its demands in the parliamentary representative system. On the other hand, national Executives found fiscal and political limits to the expansion of their action in the context of the crises of the Welfare State. New demands for rights - made outside the party system, even when requesting the creation of legislation - were directed at the Judiciary, seen as the decisive arena for their realization. It is in this sense that access to justice is now perceived as a privileged gateway to other rights of citizenship in the contemporary world, while formerly it was related to civil rights (Cavalcanti 1999).

Social policies in the 1988 Constitution and the Judiciary

Although it is not the purpose of this study to closely examine the relationship between the phenomena of the multiplication of rights and of the expansion of the judicialized social sphere, we begin by ascertaining that both appeared and gradually consolidated in the context of the Brazilian democratization process and from the enactment of the 1988 Federal Constitution.

Regarding the first point, the 1988 Federal Constitution rewrote the range of collective and diffuse social rights attributed to Brazilian citizens, introducing new and complex requirements in terms of the public policies to be designed and implemented by the State. The introduction of the concept of social security, the definition of health as a universal and equal right, as well as substantive changes with regard to social rights such as education, welfare, housing and many others, could only become concrete based on new public choices. In the vast majority of cases these new choices required not only changes in direction, but also new institutions, which initiated a broad process of legal, regulatory and organizational disassembly and reassembly, which configured a new arrangement for sectoral public policies in the social field.

Concomitantly, in the juridical field, the understanding of the binding character of the new constitutional norms on social rights was impacted. Inserted into the constitutional text in the segment assigned to fundamental rights and guarantees, social rights are absorbed into the legal system as intangible, therefore not open to interpretation by the acting government, as well as having the status of being pétreos, i.e., as if written in stone. But it is the impregnation of this system by the doctrine of effectiveness4 (Barroso 2008) that raises the question of the immediate applicability of constitutional norms, now submitted to the attribute of imperativeness and, therefore, taken out of the context of the analysis of the circumstances under which their non-realization would be noticeable. The precept of strict adherence to the commands contained in these norms resulted, in turn, in a change in the relationship between the government and the laws, giving the latter not the character of a normative ideal to be pursued, but of the generation of subjective rights which the former could not refuse, either by omission or by action. Hence, any refusals or violations of such rights would justify the tutelage of the judiciary system in order to restore the order advocated by the Federal Constitution.

Under the combination of these two movements, the problem of delimitation of boundaries between the spheres of action of the Executive and Judiciary with regard to social policies is relocated. It also presents itself in other spheres of the State's action. The functional differences between the subsystems of politics and law become unclear (Campilongo 2000).

The first subsystem embodies the democratic principle of people's sovereignty, once subjected to the democratic procedures for the formation of majorities, which gives it legitimacy to choose priorities and make choices that, presumably,5 lead to the design and implementation of public policies required to achieve the new social rights. The second embodies the constitutional principle of respect for fundamental human rights, among which the existential minimum is included (Pimenta 2008; Barroso 2008), which gives it legitimacy to assume the guardianship of social rights, albeit through interference in the actions of the Executive. To this end, in the Brazilian case, the reformulation of Justice institutions created more favourable conditions for its intervention in areas traditionally occupied by social movements and political parties (Cavalcanti 1999). A noteworthy fact is the key role attributed in the Federal Constitution of 1988 to the Public Prosecution Service (Ministério Público (MP)), an independent institution not linked to any of the branches of government, defined as essential for the jurisdictional functioning of the State and with the roles of defending the legal order, the democratic regime and of unalterable individual and social interests (Article 127; emphasis added).

In this process of internal rearrangement of power in the sphere of the State, the rise of the Judiciary compared with the other branches would be associated with processes that have global dimensions, such as: the fragmentation of social representation; the depletion of the Welfare State, founded upon the Executive's action in the face of social demands; the end of social utopias and the deflation of various forms of party-political participation (Sorj 2004). Different forms of judicial activism related to this new phase, including not only the issues related to the defence of social rights, but also other interfaces with the political sphere, have been designated as the "judicialization of politics".

Following up these processes, studies have proliferated in Brazil and abroad, whose object is limited to the phenomenon. However, there is no consensus on the term to be used or as to its use. As stated by Maciel and Koerner (2002, 122), "the academic production is also fluid in its use of the term, which is merely a name that is taken as a starting point for analyses with very different perspectives".

Despite this fluidity, it is worth highlighting the concept by Tate and Vallinder (1995), a reference that is well known and cited in the national literature, according to which judicialization refers to the process of expansion of powers to legislate and enforce laws by the judicial system and represents a transfer of decision-making power from the Executive and Legislative to judges and courts:

Judicialization of politics" and "politicization of justice" are both correlate expressions that indicate the effects of expansion of the Judiciary's power in the decision making-process of contemporary democracies. To judicialize politics, according to these authors, is to use methods typical of the courts in resolving disputes and demands in the political arenas in two contexts. The first would result from the expansion of areas of operation of the courts through the power of judicial review of legislative and executive actions, based on the constitutionalization of rights and of the mechanisms of checks and balances. The second, more diffuse context would consist of the introduction or expansion of court staff or legal proceedings in the Executive (as in court cases and/or administrative judges) and the Legislative (as is the case with the Parliamentary Inquiry Committees) (Maciel and Koener 2002, 114).

Tate and Vallinder call the first form of judicialization "from without" - which refers to the Judiciary's reaction in face of the provocation of a third party and aims to review the decision of a branch of government, based on the Constitution. They call the second form judicialization "from within" - the use of members of the Judiciary in public administration.

Reviews of ways to use the concept were and continue to be made, and its use has also lent itself to various regulatory approaches, but our goal here is not to redo this survey6. We merely emphasise that much of the debate has been organized around themes such as the scope and significance of constitutional review as an attribute of the Judiciary in the light of the actions of the Legislative and Executive (Tate and Vallinder 1995; Oliveira 2005) and distinct models of Republic that correspond to different patterns of relationship between these powers (Maciel and Koerner 2002).

From the empirical point of view, we have no evidence that enables us to categorically respond to what extent the acts of control of the Judiciary over the other branches are restricted to the legal field or whether they affect contents that are eminently political. In this sense, open questions remain: what is the intensity of judicial policy-making (Guerra 2008)? What are the parameters for its intervention, particularly in the case of public policies defined within other branches of government?

From the normative point of view, the questions converge to the qualification of the effects of its intervention: whether the Judiciary's political activism is an obstacle to the development of citizenship or whether it is a form of expansion of citizenship itself. In other words, whether "judicialization" is an extension of democracy and an expansion of citizenship or whether, instead of guaranteeing rights, it contributes to enhance the asymmetry of rights in Brazilian society. The answers relate to the ambivalence noted by Reis (2000), referring to Kelly (1979), regarding the civic and civil dimensions that constitute the notion of citizenship. The first is tied to the idea of duties and responsibility of citizens, to the propensity to behave with solidarity and observe civic virtues. The civil dimension is linked to the assertion of the rights of individual members of society and is present in the assertion of civil, political and social rights. In the latter, the members of a collectivity assert themselves autonomously in the private sphere. The ambivalence refers to the fact that, ultimately, the values of one of these dimensions deny the values of the other dimension. The resulting tension is that the private sphere is one in which particularist interests assert themselves while the civic sphere is that in which solidarity and collective interests are asserted. It follows, then, that political life involves dealing with this tension between the pursuit of individual interests and the definition of foci of solidarity and collective identities.

It is precisely from this latter aspect that we take up the paradox that is established from the absorption of social rights in the 1988 Constitution. When those rights are treated as fundamental and, therefore, are directly protected by the Judiciary, they are submitted to an institutional operation that distances them from the bases of social solidarity that created them. As stated by Roberts (1997), social rights, by their very nature, have a collective character that differs from individual rights and responsibilities associated with civil or political citizenship, based on the individual exercise of rights and obligations. They correspond to a dimension of citizenship that arises from an egalitarian insertion in the community, linked to a shared status based on which the citizen "is willing to hand over to the State the resources and authority necessary for it to act in the interest of the collective" (Reis 2000, 218-19). At this point a tension between individual and collective interests emerges; it openly manifests itself in the case of public health policies.

Right to health: conceptual innovations and review of the boundaries between Executive and Judiciary

The right to health is one of the guarantees that comprise the system of fundamental rights that is the target of judicial activism based on the legal order established by the 1988 Constitution.

The Brazilian Health Reform Movement - a result of the combination of experiments in alternative care models with a build-up in critical thought in academia and social movements linked to the sector - was a successful collective initiative with regard to the incorporation of rights into the 1988 Constitution. Based on propositions derived from the 8th National Health Conference7, health is covered in Article 196 of the Constitution as resulting from "social and economic policies aimed at reducing the risk of disease and other health problems and the universal and egalitarian access to actions and services for its promotion, protection and recovery".

From a conceptual standpoint, the Constitution separates the right to health from strict access to curative action of medical procedure and understands its guarantee as a result of a range of public policies able to impact the conditions of existence and creation of citizens' autonomy. Even in the case of strictly sectoral actions, health is perceived as resulting from the combination of "actions and services for its promotion, protection and recovery" more specifically translated in Article 198, Paragraph II, in the constitutional directive "integral care, with priority given to preventive activities, without prejudice to assistance services".

This conceptual shift, however, is apparently overshadowed in conflicts between the Executive and the Judiciary, with the latter clinging to the first part of Article 196, which states that "Health is a right for all and a duty of the State". Originally, the "right for all" was advocated by the Health Reform Movement as the collective right of all Brazilian citizens, breaking the contractualist principle that formerly restricted access to public healthcare to the population inserted in the formal labour market. But this is not the meaning that the Judiciary gives it, since it is the depositary of individual suits claiming the provision of specific services or inputs by the government.

Such lawsuits typically relate to services or inputs that are not available to every citizen under the usual procedures of the Single Health System (SUS). There is a perception in the literature that there have been an increasing number of lawsuits in recent years, leading to Judiciary decisions that amply favour their beneficiaries (Pimenta 2008; Borges and Ugá 2010).

As for the impact, there are records that show results from different aspects. From the point of view of the Public Administration, the cumulative effect of such suits is the disruption of the planning and scheduling formulated for the sector in each sphere of government, since these lawsuits mostly deal with services and inputs that are prohibitively expensive. This is even more serious considering the previously set budget limits and the scarcity of resources, which implies the need to "make choices, often difficult ones, between the various possible health policies" (Ferraz and Vieira 2009, 227). From the social point of view, although without empirical evidence, there is a perception that these actions have a concentrating effect, favouring the middle segments or even "the highest income segments of the population" (Borges and Ugá 2010, 67), generally the better informed segments that have greater access to the Judiciary.

The third aspect concerns the loss of control by the Executive over the maintenance of scientifically sustained parameters of safety, efficacy and effectiveness of goods offered by the public sector. This loss is noticeable in the allegations made by the Minister of Health at a public hearing carried out by the Supreme Federal Court (STF 2009a, 9):

I believe that the judicial route educates negligent managers that within their competency and responsibility do not provide the goods and services for health, but I also think that this path cannot become a tool for breaking the technical and ethical limits that support the Single Health System, imposing the use of technologies, goods or medication, or their uncritical incorporation [emphasis added], disorganizing the administration, shifting resources from planned and prioritized destinations and, what is more surprising, often harming people and putting their lives at risk.

As well as the Ministry of Health, state and municipal managers have shared this negative assessment, made public by the respective representatives of the National Council of Health Secretaries (CONASS) and the National Council of Municipal Health Departments (CONASEMS), at the abovementioned hearing (STF 2009c; STF 2009d).

Although many who work in the Judiciary might be sympathetic to such assessments, there is a widespread perception among others, as well as among officials of the Public Prosecution Service and Public Defenders' offices, that the Judiciary's action is positive and essential for ensuring compliance with the constitutional obligation emanating from Article 196. They are joined by associations of people with specific diseases and groups linked to the pharmaceutical industry, among other segments. The immediacy of access to preserve the life or health of a patient is a central component in support of this perspective:

Therefore, we believe, Mr. Minister, that it is the State's duty to guarantee its citizens the right to health, and that it is inconceivable to refuse the supply of free medicine to patients in a critical condition who are unable to bear the financial costs of these drugs needed for their treatment, whether this drug is simple or high-cost, as long as the non-administration of this resource endangers the life of the affected individual. This has not been fulfilled by the Single Health System. Universal and equal access, highlighted in Article 196 of the Constitution, leads to the understanding of therapeutic care, and that automatically includes pharmaceutical care [emphasis added] (STF 2009b, 2).

Based on the terms put here, a clear distinction between the discursive structures that bolster each position is presented. In the first, there is explicit acknowledgement of conflict between individual and collective rights to health. The option for the former would preclude optimal public choices from the technical and financial point of view, conflicting with the elements of solidarity and redistribution of social policies by having a concentrating effect. Having accepted that, the Judiciary should revisit criteria (Barroso 2008; Pimenta 2008) to deal with these individual suits, while preserving established technical patterns and choices of budget programming, as well as isonomic treatment between citizens, to avoid the situation that people with access to justice are better served than other citizens.

In the second, the issue of collision between individual and collective rights is not stated: the option to answer the claims in individual suits would correspond, purely and simply, to the immediate application of a constitutional norm in order to restore an infringed fundamental right. It would be up to the Judiciary to simply observe minimum formal aspects that make up the individual suit, particularly a medical prescription explaining the need for the supply of certain inputs or procedures by the government for the preservation of life or health.

The second position, widely prevalent in the Judiciary, even if it does not acknowledge it, has no way of avoiding a problem of logical consistency between individual and collective rights. As summarized by Borges (2007, 23), the main problem

(â¦) arises when health is seen as a private good, or in legal terms, as a public subjective right. In these situations, the exercise of subjective rights against the State by a certain individual may affect the exercise of the subjective rights of other citizens, becoming in these cases an exclusive good of rival consumption.

Thereafter, according to the author, health stops being a right of citizenship guaranteed to the entire population to become a private good of exclusive consumption, to be fought over by all citizens.

The Research Question and the Methodology

The formulation of the question on the terms proposed here has two levels of analysis to be explored using elements that distinguish the positions described above. At the first level, we ask ourselves to what extent can one say that the use of the Judiciary - when basing its decisions on the restoration of individual rights through the immediate implementation of constitutional norms - has affected, in practice, the collective dimension of the right to health? The answer at this level involves the exploration of a set of additional questions such as: the extent to which judicial decisions have served the defendant in an individual suit; how government allegations citing the effect on conditions to serve the collective have been considered by the judges; the existence of negative repercussions in terms of financial or administrative budgets; or others that point towards a collision with the accomplishment of the right to health as equally available to all.

At a second level, we ask what are the aggregate distributional effects produced by the intervention of the Judiciary on the basis of the various individual suits. The answer, at this level, involves the exploration of another set of issues: the institutional origin of medical care that generated the prescriptions (patients from the public, private or health plan sector?); the average cost, per suit, of the inputs or procedures provided; and the social origin of those benefitted, among others.

The elucidation of the issues raised by these two analytical levels guided the choice of the methodological procedures used in this research.

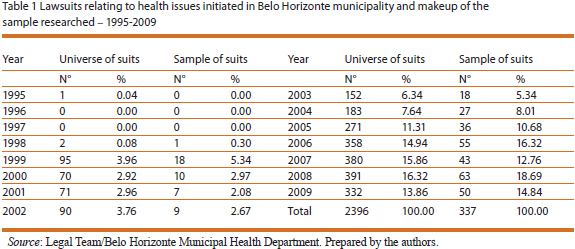

Healthcare-related lawsuits filed in Belo Horizonte were the object of this research. Since there is little organized data in this field, the first step was to conduct a manual count of cases in the files of the Municipal Health Department's legal team. A total of 2,396 cases were recorded between the years of 1995 and 2009. Of this total, a sample of 339 cases was analysed8. We constructed a form to record information identifying relevant features, considering the research question, including: general identification data of the suit; the petitioner or beneficiary9; the characteristics of the goods or services requested and the transaction of the process; and, especially, the parties' arguments and the decisions.

The second research strategy was to analyse financial aspects related to the execution of the legal action in question, from data regarding procurement processes, provided by the Municipal Health Fund of Belo Horizonte (FMS/BH) between 2007 and 2009, the only period with data available. Data were grouped by expense item, according to the accounting classification used by the FMS/BH. One methodological option was to work preferentially with paid rather than committed expenses, since they were actually paid, therefore portraying the financial impact of lawsuits. Committed expenses often refer to an estimate that may or may not materialize and they were only used in cases where there was no available information regarding paid expenses. Lastly, it is worth clarifying that rather than identifying a conclusive definition of the term judicialization of politics, we used it here with a precise and narrow definition, as referring to the recurring process of citizens individually using the Judiciary, in order to obtain access to services or goods based on a certain conception of the right to health. Our goal is to construct an interpretation of the effects produced by this process. We considered the effects both from the point of view of State/society relationships in the field of health policies, and from the point of view of the quality they impose on government decisions regarding the implementation of these policies, including those concerning the allocation of resources and services to be rendered by the Single Health Service (SUS).

What citizens request and what judges decide

The data indicate that there is a gradually increasing trend of litigation to obtain medical services or inputs needed for health. In other words, citizens of Belo Horizonte have increasingly used the courts to obtain what they would otherwise be denied if they used the normal mechanisms of access to the public health system, either because the supply is scarce (such as when there is a queue to receive medical procedures) or because they are not guaranteed by the current policy (as in the case of medication not on the SUS list, special diets, equipment etc). This process, which began in the city in 1995 with a single lawsuit, became common by the late 1990s and has been growing significantly since 2005, reaching a peak in 2008, when 391 suits were filed - more than 16% of the total for the entire period until 2009.

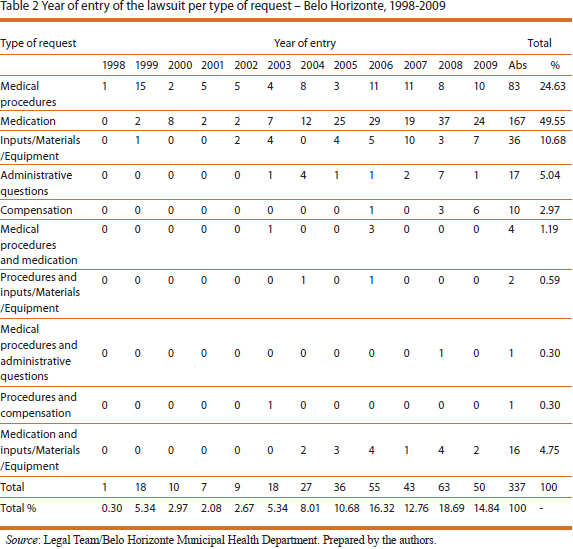

Considering the sample surveyed, it appears that almost half of the lawsuits filed during this period (49.55%) refer to requests for medication not distributed by SUS (Table 2). These are followed by suits regarding the performance of medical procedures (24.63%)10 and to a lesser extent those requesting inputs, materials and equipment needed for health. There was a significant increase in demands for drugs from 2005, which is the type of suit responsible for the growth in "judicialization" in the period.

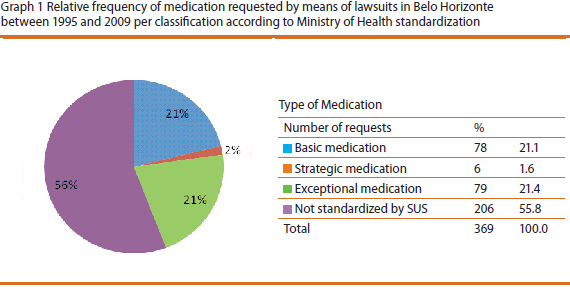

The specific analysis of requests for medication makes it clear that 56% of petitioned items are not standardized in SUS tables, i.e., due to a decision by SUS management, they are not offered for the following reasons: low or dubious efficacy, low cost-effectiveness etc11. Among the 44% which are standardized, 21% refer to medicinal products for exceptional use (high cost) and 21% to basic drugs and 2% for strategic drugs12, as shown in Graph 113. The analysis shows that 99% of items are sold in Brazil, which means that requests for medication that needs to be imported are exceptions.

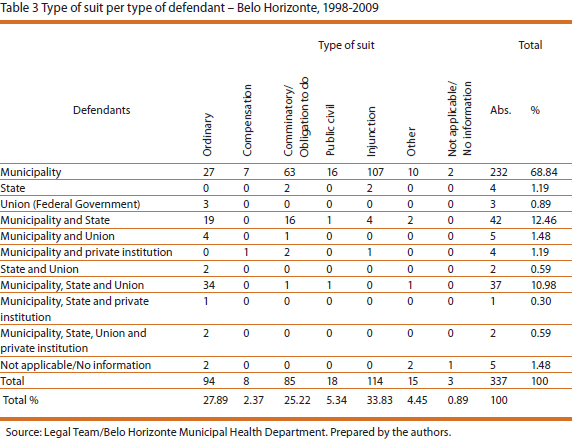

Although the research focuses on lawsuits filed in the Municipality, in some cases other units of the federation are also the object of the action as defendants. Although only about 70% of them were originally directed exclusively at the municipality and/or municipal officials or institutions, in approximately 96% of cases the Municipality (or municipal officials and employees) was the defendant along with another unit of the federation or along with private service providers of SUS (Table 3). Since the Municipality is legally responsible for the health of its citizens, even if the services are being equally provided by the three levels of government, many lawsuits are against the Municipality because it is considered as being ultimately responsible. Lawsuits directed at more than one federal entity are more usual in the case of medicines (36%), considering that pharmaceutical care is the responsibility of the three levels of government, albeit with diverse assignments.

The largest number of cases (34%) is of the injunction type, that is, they are orders issued by a judge that must be acted upon, with no defence or counter-arguments by the other party. Next come lawsuits that are of the ordinary and comminatory type; the former is used to ensure a right or fulfil a civic obligation and the latter "appropriate under obligations to do or not do"14 ( www.jusbrasil.com.br), which together account for over half the lawsuits. A small percentage of suits (approximately 5%) are of the public civil action type, i.e., procedural tools of which the Public Prosecution Service and other entities entitled to defend homogeneous diffuse, collective and individual interests can make use. Their aim may be financial penalization or the fulfilment of an obligation to do or not do, and they cannot be used for the defence of rights and interests that are purely private and alienable (http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki)15.

As expected, the Public Prosecution Service (MP) was responsible for 16 public civil suits. In 13 of these, it acted on behalf of minors, and in two cases, on behalf of seniors. In another case, it filed a petition for administrative impropriety, considering that several patients sought the MP because they could not find a necessary, standardized medicine that was supposedly available through SUS, at pharmacies in the Municipality. There was also a situation in which the judge did not rule on the merit of the suit on the grounds that the MP had no legitimacy to file the case. In the remaining cases, the MP acted according to its competencies16 that is, it acted in defence of children and the elderly, and also put pressure on the public administration, forcing the agile supply of standardized medication. In this case, the MP did not press for the provision of goods or services that are not supposedly provided by the public system, but seeks to ensure that the legislation is fulfilled. However, the low relative volume of lawsuits filed by the MP points to the prevailing form of suing and functioning of the Judiciary in the health field: ensuring special benefits for certain citizens in an atomized fashion.

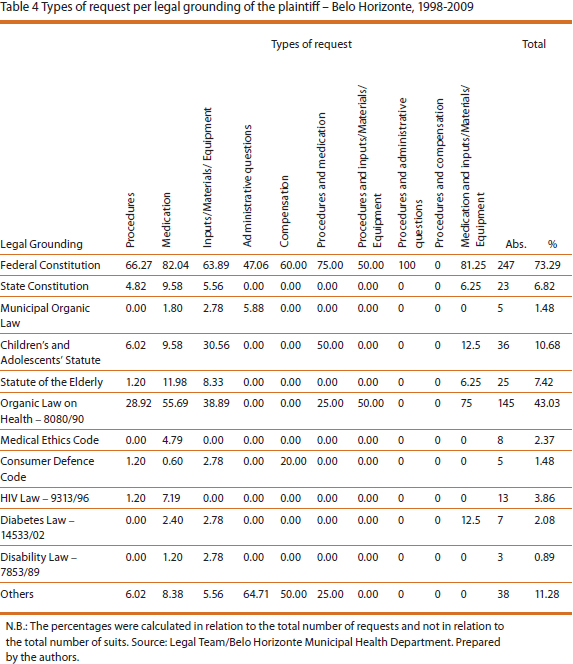

Obviously this does not happen in a legal vacuum. The primary legal justification for the requests is the Federal Constitution, used in more than 70% of cases, followed by the Organic Law on Health (Law 8080/90), in 43% of them; only in the case of lawsuits whose objectives are administrative issues is this not the case (Table 4).

In some cases, the reasoning is based on laws that are specific to certain segments of the population, such as the Children's and Adolescents' Statute, the Statute of the Elderly, the law that guarantees healthcare for diabetics (14533/02)17 or the Disability Law (1853/89)18. If in the first case the state law for care of diabetes clearly ensures medication and supplies, the same cannot be said of the law relating to disabled people, which has a very broad content, and its use to justify procedures that are different from other citizens through the courts is questionable.

Article 196 of the Constitution, which is part of the section specifically on health issues, is the basic legal reasoning to justify the requests, mentioned in almost 62% of cases, followed by Article 6 (44%) and by Articles 198 and 5, which account for 35% of cases19. This is predominant, regardless of the type of solicitation, except in cases of compensatory or administrative suits.

The reasoning based on Article 6 (defining health as one of the social rights) points to the rationale that guides suits based on the assertion of rights, which, if not guaranteed, justify legal action. It is worth mentioning that the article in at hand falls under Title II of the Constitution, which deals with fundamental rights and guarantees.

It is curious that more than 35% of cases are also based on Article 5 of the Federal Constitution, which states that all are equal before the law, without distinction whatsoever, guaranteeing Brazilians and foreigners residing in the country the "inviolable right to life, liberty, equality, safety and property". In other words, the right to equality is enlisted to obtain differential goods and services, which implies that citizens were being discriminated against by not having access to certain goods that are supposed to be guarantors of the constitutional right to health. Article 3, which defines the basic objectives of the Brazilian Republic is also evoked in 15% of cases, to justify individual requests20.

In more than 70% of cases, injunctions were granted, i.e., court orders issued before the ruling on the merit of the suit, as a way of ensuring that a citizen has immediate access to a certain product or health service. In the case of drugs, this percentage reaches 80%. In 36% of injunctions, a daily fine is set for non-compliance; this can reach R$ 5,000.00. It is plausible to suppose that immediate compliance with the injunction may have the effect of forcing the Executive to purchase medicines without following legal procedures, such as the official tendering process, which means that compliance with the court order may lead to the violation of another law, as well as disrupt the budget and sectoral planning. When there is the immediate determination of the completion of medical procedures to guarantee the "right" for one, the fulfilment of others' right may be delayed, especially hospital admissions, bearing in mind the difficulties of access to certain health services that characterize public healthcare. Mechanisms for organizing and controlling access, such as the SUS hospital bed referral centre, which manages waiting lists and monitors the free beds available, are ignored to comply with the court order.

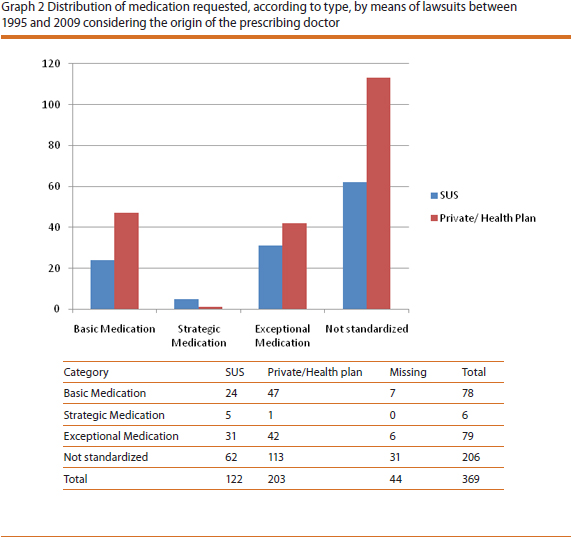

Considering the totality of cases examined, it is remarkable that most of the physicians who endorse the requests (64%) that give rise to the legal actions work for SUS, and supposedly are aware of the health policy and rules. The rest are private physicians or ones who work for health insurance plans, which means that citizens who do not use the public healthcare system also use the Judiciary to obtain benefits from it.

However, if we consider all the medication requested, instead of all the legal cases, it is curious that among the items solicited - where it was possible to trace the physician's institutional origin - 63% were by private doctors or those linked to health plans and only 37% by SUS physicians. Among non-standard medicines demanded by lawsuits to be supplied by the public system, the relative shares are 65% and 35%, respectively (Graph 2).

But who are these citizens who use the justice system?

Information contained in the proceedings concerning the profile of beneficiaries of the proposed suits includes age, gender, occupation and address. However, in a large number of cases such information is not available, which makes it impossible to make more consistent or generalized conclusions, even though there may be indications. Besides the absence of information, it is worth highlighting that the information about occupation is quite imprecise, and often does not allow the characterization of the activities that were carried out, as in the cases of people who are retired, public employees and the self-employed. An aggregation was carried out of several activities that appear in small numbers in the category "occupations that do not require higher education". Even acknowledging that there is some simplification, this categorization has the advantage of excluding professionals who hold a university degree21.

Beneficiaries' addresses were used to define the "degree of risk of the place of residence", with reference to the classification adopted by the Belo Horizonte Municipal Health Department to plan its actions using the Health Vulnerability Index22. Several indicators are considered in order to construct the area of vulnerability to health. These include sanitation, housing, education, income and health, and lead to the classification of census sectors in the following categories:

- low risk: areas with below average values

- medium risk: census sectors with health vulnerability index values with half standard deviation around the average

- high risk: sectors with above average risk values up to the limit of one standard deviation

- very high risk: areas with values above high risk

Regarding age, for cases in which this information is available (only 32% of the sample), it appears that 50% of the beneficiaries of the suits filed in the city of Belo Horizonte, where the object was access to health goods and services, were under 30 years old, but a significant percentage were more than 60 years old (36%).

With respect to occupation, data were identified for 72% of the sample. Among these, more than half the beneficiaries were employed, part of them in occupations that require no college degree (19.4% of total). The retired, public employees and independent workers accounted for around 23%.

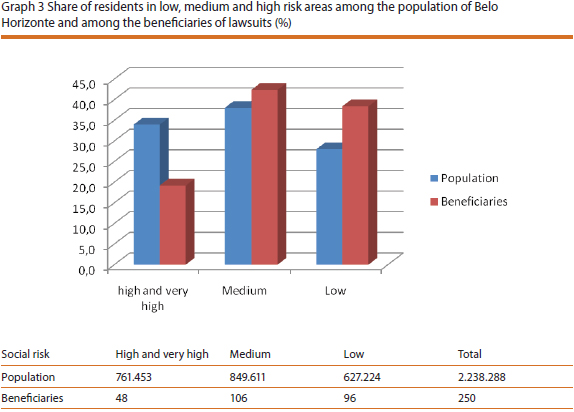

As for the risk of the place residence, a good predictor of beneficiaries' socio-economic status, and also considering the cases in which information is available, the highest incidence was for medium risk (42.4%), followed by low risk (38.4%), with a significant percentage of residences with high risk (19.20%)23. It was not possible to identify this variable for one quarter of the sample. Using the part of the sample where identification was possible, if one compares the distribution of the three categories with the population of Belo Horizonte, important elements come to light for the discussion of one of this study's hypotheses. For the categories of medium and low risk to health, the share of beneficiaries is higher than that of the general population (38% and 28%, respectively), while the participation of the high risk and very high risk categories is lower than for the general population (19.2% and 34%, respectively). Graph 3 illustrates this regressive effect.

If one cannot state that residents of low risk areas are the main beneficiaries, the available data indicate that their participation is proportionately larger than in the general population, unlike residents of the high social risk areas. However, one cannot state that only those with a higher socioeconomic status have valid access to justice in order to have access to services and inputs in the health sector. Citizens belonging to high risk areas have also been using, in a very significant proportion, the instruments available to seek to enforce what they consider to be their right, as is the case with the Public Defender's Office.

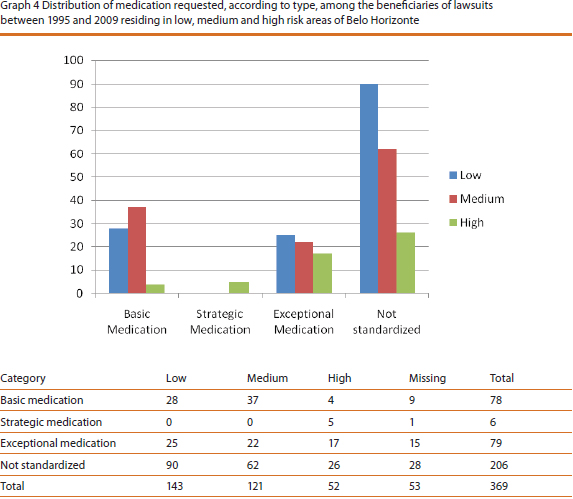

Regarding the medication requested by lawsuits, there is an interesting configuration of distinct profiles for the type of medication required by citizens in different risk categories. The non-standard and exceptional or high cost medicines are mostly requested by citizens living in areas of low risk (50% and 39% of requests, respectively). Strategic drugs, albeit with low frequency, were all requested by residents in high risk areas, while basic medicines were mostly requested by residents in areas of medium risk (54%), as shown in Graph 4.

There is also a relationship between the risk level of the area of residence and professional activity, despite the inconsistencies of information concerning the latter. The unemployed and those in occupations that require no college degree have a much greater proportion of residences in high risk areas (25% and 26% respectively) when compared with professionals that have a university degree (only 10%).

Forty three per cent of the lawsuits are filed by private lawyers and about 40% by public defenders, free attorneys or members of the Public Prosecution Service (the latter focused on lawsuits whose beneficiaries are minors or the incapacitated). Furthermore, in 80% of cases there is a request for exemption from court costs.

The data suggest that access to justice for an alleged right to health is not restricted to citizens with a higher socioeconomic status. Free access to justice, particularly through public defenders, has expanded and citizens who use SUS also count on medical professionals to make requests outside the parameters of the public system. Considering that the Judiciary is one way of guaranteeing rights, this is taking place in a more "egalitarian" fashion among the citizenry.

Considering the suits for which this information is available, among holders of university degrees, there is a prevalence of requests made by private physicians or health plans: 7 out of 8 requests. Among those whose occupation does not require higher education, the proportion is of 9 private physicians to 30 from SUS. There is also an inverse relationship between the risk level of the area of residence and requests by SUS physicians, i.e., the higher the risk, the greater the number of requests made by SUS physicians - 65% of requests made by residents of high social risk areas are made by SUS physicians, compared with only 4% of requests from beneficiaries residing in low risk areas.

And how does the Judiciary operate? What do judges decide with respect to requests?

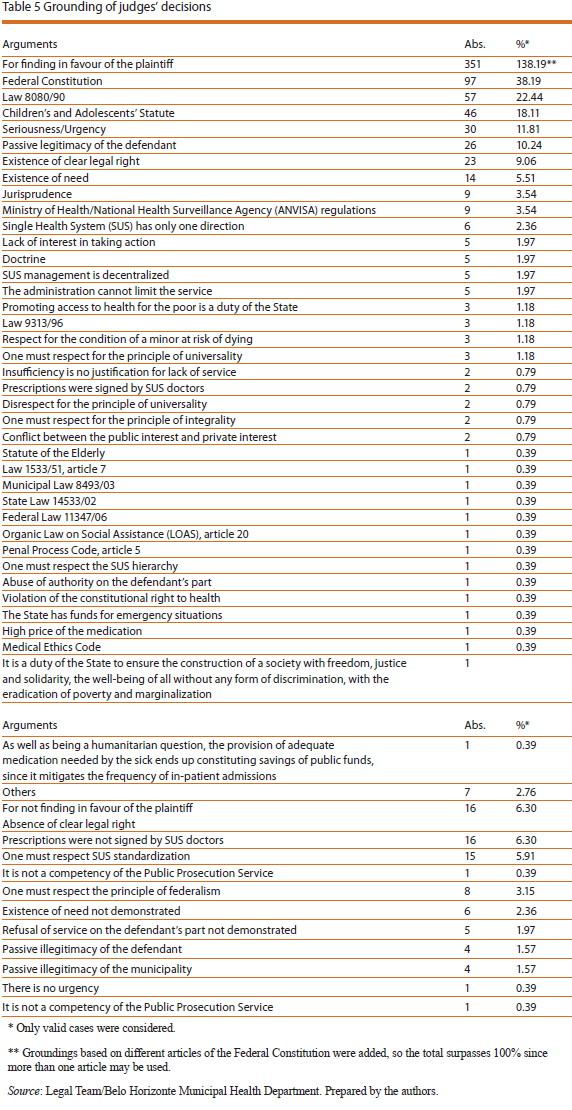

Our analysis suggests that judges grant requests 90% of the time, fully or partially24. In all such cases, the reasoning is based on the Federal Constitution, in particular on Article 196, reaffirming that health is a right for all and a duty of the State, and it is up to it to ensure universal and equal access to health services. Next come rationales based on the Organic Law on Health (Law 8080); it is also worth mentioning the rights of children and adolescents, as expressed in the Children's and Adolescents' Statute (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente (ECA)), in 22% of cases. In many arguments, the right to health is regarded as a "clear legal right" that cannot be questioned. The responsibility of the Municipality is also reaffirmed based on Law 8080/90, considering the decentralization of the public system and the integral nature of healthcare, interpreted as access to anything that may be necessary25. Among the main arguments that justify the granting of requests one finds the poverty of the beneficiaries, the "clear legal right", risks to health or even risk of death. Table 5 lists the elements that underlie and justify judges' decisions both to grant and refuse requests.

One interpretation of the State's obligations to guarantee the right to health refers to the need to guarantee it to the poorest, reinforcing an image of the SUS as a system focused on the poor.

From a broad interpretation of constitutional provisions, the claims of the Executive relating to restrictions on healthcare are disregarded, as seen from the following statements:

The Public Administration may not limit the scope of constitutional rule, which is broad, absolute and unrestricted.

Economic and budgetary arguments also cannot override the right of the citizen, because the right to health and life overrides any other contained in the Constitution itself.

However, there are cases where judges' arguments take into account the rules that guide health policy, with greater connection with decisions made by the Executive and that are articulated with concrete limitations in the execution of constitutional provisions. In these cases, judges demonstrate knowledge of norms that govern SUS and argue for the need to replace drugs with those supplied by the public system; they defend the need for expert opinions by SUS physicians; they reject requests when made by physicians who do not work for the SUS; they request an assessment of the possibility of replacement of medicines or treatments by others that are equally effective; they reject claims when a plaintiff has not demonstrated financial need (reinforcing the image that the SUS is for the poor) and also consider the "absence of clear legal right". Examples of a different and narrower perception of the right to health, as well as non-interference in the decisions of the Executive, are the following statements:

The right to health guaranteed by the Constitution does not imply an obligation by the public sector to provide the citizen with any kind of test that exists, but rather to provide appropriate treatment, observing the principle of reasonableness, which rules out the possibility of demanding special treatment.

There is no way that the Judiciary can interfere with the health policy established by the Administration. There is also no evidence that one of the tests requested is essential. As for the other test, the Municipality has acknowledged its obligation to provide, since it was requested by a SUS physician and is part of the standardization table.

Budgetary and financial aspects and resource allocation

Although the data made available by the Belo Horizonte Municipal Health Fund only cover 2007, 2008 and 2009, it is possible to identify important elements that advance the goals of this study.

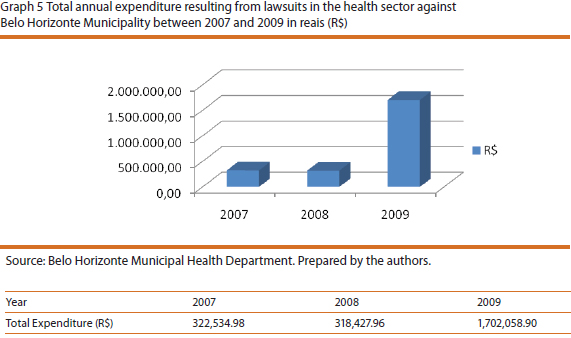

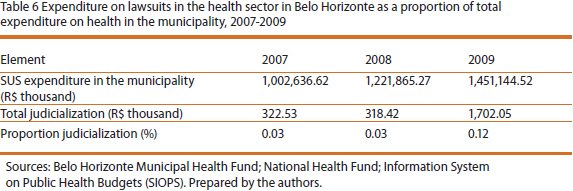

Firstly, one can see that total expenditure on litigation in absolute levels is similar in the first two years, and actually declined by 1.3% from 2007 to 2008 (from R$ 322,534.98 to R$ 318,427.96). However in 2009, costs grew strongly, reaching R$ 1,702,359.11, which means an increase of 434.5%, as shown in Graph 5.

Despite such intense growth, total spending on lawsuits still accounts for only a tiny proportion of the municipal health budget (less than 1% - Table 6). However, there is a dramatic increase in the cost of lawsuits in 2009 - four times greater than in 2008 - which might mean an upward trend that only the data for the next few years could confirm.

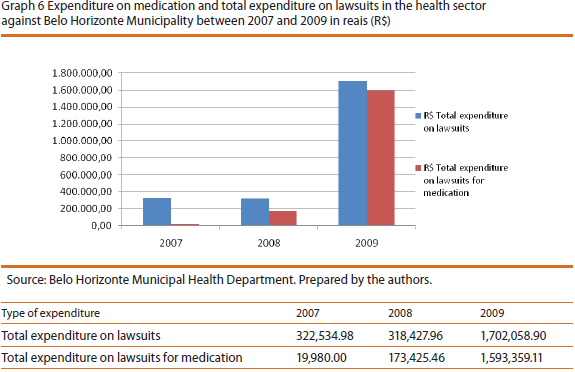

The analysis of the composition of total spending in the three years per expense item, even considering the short time period, contains revealing information. While spending on foodstuffs and other materials to be provided to citizens by SUS26 represented, respectively 37.4% and 38.8% of total expenditure on litigation in 2007, spending on these items decreased in 2008 - when together they totalled 23.2%27 - and 2009, when they reached just 2% of total spending. In contrast, medication, which in 2007 represented only 6.2%, jumped to 54.5% in 2008, and to 93.6% in 2009 (Graph 6).

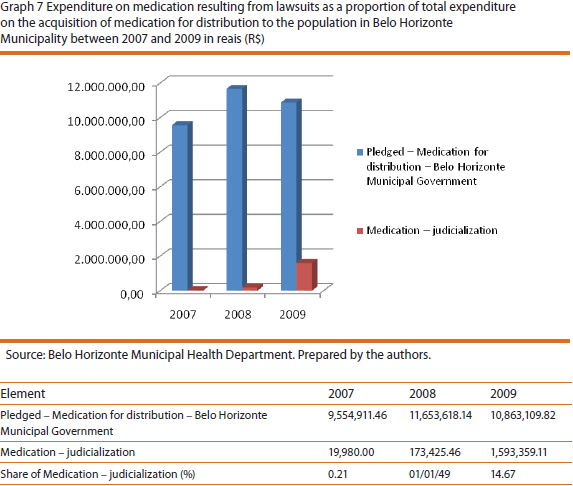

Given the weight that medication has reached in the expenses on lawsuits, it is important to explain in greater detail the financial impact of such spending, considering the SUS policy of funding pharmaceutical services. According to this policy, municipalities' responsibility in funding these inputs should be limited to matching the resources transferred by the Union (federal government) and states for prescription drugs at basic care level28. However, comparing the expenditure on medication granted due to lawsuits against the total expenditure on medicines for the population29, provides one with a more accurate picture of the rising impact of the former on the latter (Graph 7). In 2007, expenditure on medication owing to lawsuits represented just 0.21% of the total spent on drugs for distribution, which was R$ 9,554,911.46; in 2008, 1.49% of R$ 11,653,618.14; and in 2009, it reached 14.67% out of the R$ 10,863,109.82 spent on medications by the Municipality.

It is also possible to analyse the budgetary and financial data based on the per capita spending and, in this specific case, it is worth making some comparisons with more general information provided by the Information System on Public Health Budget (Sistema de Informações sobre Orçamentos Públicos em Saúde (SIOPS)).

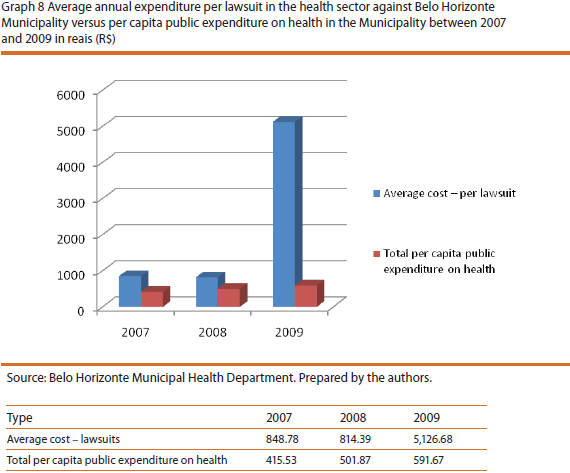

According to this information, in 2007 per capita expenditure on health30 was R$ 415.53 in Belo Horizonte Municipality, a figure that rose to R$ 501.87 in 2008 and R$ 591.67 in 2009. Using this information as a baseline, one way to assess the distributive effects of individual lawsuits is to compare their average cost in each year with per capita expenditure. Considering these values to be R$ 848.78 (2007), R$ 814.39 (2008) and R$ 5,126.68 (2009), Graph 8 illustrates the discrepancies. It is worth noting that in 2009, the average cost of a lawsuit for the Municipality rose to almost 10 times the per capita public spending on health in the Municipality.

One can ponder that, since per capita expenditure on health in the Municipality includes other goods and services, directly or indirectly31 provided to the beneficiary of the lawsuits, one should not forget that its "cost" to SUS per year was higher than the average cost of lawsuits. It is also noteworthy that for each citizen individually assisted in his/her lawsuit, resources worth almost 10 times the SUS per capita expenditure in the Municipality - which includes the promotion, protection and restoration of health - were consumed in 2009.

Final Remarks

The study of "judicialization" of health in Belo Horizonte enables us to measure some characteristics of this process and suggest some conclusions. The concept was used here with a restricted and precise meaning, and refers to the actuating of the Judiciary by citizens with the aim of obtaining differential or faster access to health actions and services - a phenomenon increasingly observed in the Municipality of Belo Horizonte. The outcomes of judicial decisions get superimposed on other decisions made by the branch responsible for health policy (the Executive), seeking to give substance to the constitutional right to health. The judicialization of health, as defined here, highlights the contemporary trend of access to justice as a privileged gateway no longer only for the achievement of civil rights, as was the case in the constitution of citizenship rights, but for other rights as well.

The study identified a relationship between rights and justice on the terms of the analysis presented by Barroso (2008) on constitutional norms and social rights, which have been absorbed into the legal system as intangible (not open to interpretation by rulers) and "set in stone". In this perspective, laws do not have the character of a normative ideal, but of generation of subjective rights, the violation of which justifies the tutelage of the Judiciary over these rights, even if by interfering in the actions of the Executive. The understanding that constitutional norms must be applied directly is a consequence of the doctrine of effectiveness, justifying the quest for its unrestricted guarantee for citizens as seen in a fragmented fashion, based on the principle that "health is a right for all". This perspective fails to consider the context of health policy execution, as well as translating this right into specific demands. The law is undetermined and allows a broad and generic interpretation of the right to health. This, incidentally, has led to the drafting of bills in the Brazilian Congress - Senate Bills 319/2006 and 219/2007 - altering Law 8080/90 in order to specify what integral care means in the SUS ambit. Therefore, as a fundamental guarantee that is immediately applicable, the right to health loses its ties to the remainder of the contents of Article 196 and becomes perceived in an atomized fashion, based on the individualized relationship each citizen-claimant has with the State in the form of a lawsuit.

Inasmuch as the Judiciary appoints itself the guardian of constitutionalized rights, it may guarantee citizens' access to services and inputs necessary for health in situations where health and lives are threatened. But, in doing so, it often interferes with the health policy that was defined taking into account the political, institutional and financial constraints of governmental action. To this extent, in meeting private and fragmented demands, the Judiciary affects the implementation of health policy and, in this sense, it may be considered a relevant actor owing to the interpretation of constitutional provisions it has been providing, which put pressure on health policy management. In some cases this is positive, in others it is not.

This leads us to a tension or a certain ambivalence in the actions of the Judiciary. If on the one hand it is decisive in securing rights in a democratic society, at the same time it interferes in the decisions of other institutions that, in principle, have been democratically defined. If on the one hand the Judiciary is important in guaranteeing constitutional rights and even expanding these rights, forcing the Executive to greater efficiency and agility, on the other, the tension can also benefit certain individuals to the detriment of the whole population, jeopardizing the principle of equal treatment for all citizens.

However, the interference of the Judiciary does not reach the health policy decision-making process due to the way it operates in the health field. It only acts when provoked, and this interference is largely the result of the demands of individuals and their private interests. They use the argument of social rights, but from an individual rights perspective. The effect may be to harm the right of others, since the logic of solidarity in social policies is not considered. If on the one hand the policy has to deal with the tension between the affirmation of individual interests and the definition of foci of solidarity, including the funding of social policies that give concreteness to social policies, on the other, the subjectivity of the right to health based on the notion of unrestricted right, acts in the opposite direction. Assuming that the right is a "clear legal right" by itself does not help in defining political forms for solving the problem of how to actualize it. A consequence is that, at least in the case of health, it cannot be said that the Judiciary makes decisions of a political content, as suggested by other assessments of the judicialization of politics. However, the Judiciary makes decisions that produce externalities on the decisions made in the political sphere. If it does not make public policy, it interferes with its implementation.

As for the financial and budgetary impact of the lawsuits, the available evidence shows that it is still residual, considering the municipal budget as a whole. But the same cannot be said when analysing spending on medication, especially if we take into account the small number of beneficiaries who consume the equivalent of 15% of total municipal spending to purchase these items. In this particular regard, it is worth remembering that the other 85% in the budget for such acquisitions is what remains for the benefit of practically the entire population of Belo Horizonte, following the SUS pharmaceutical assistance policy. The latter provides access to standardized drugs taking into account the criteria of safety, efficacy and economy. Based on this, two additional considerations are important.

Firstly, we must examine from a political perspective the fact that most of what is requested through litigation is not standardized SUS medication. If they are not standardized, this is owed to public reasons: either because they are not deemed safe by the scientific community and the public sector with reference to potential effects; or because they do not have proven efficacy; or because they damage the principle of Public Administration economy or some such reason. In these circumstances, attending to individual claims compromises a technically grounded collective choice made within the realm of the Executive32, as to what drugs should be made available to the population in the SUS ambit. In this case, attending to a fundamental constitutional right surmounts the political right of a majority, represented by the Executive, to make choices about the goods that are the object of public health policies.

Secondly, considering that the funds allocated in the municipal budget to purchase medicines to be distributed to the population is also a choice of the Legislative, based on a draft sent by the Executive, again, beneficiaries' individual interests supersede collective ones. If, in proposing a given amount, the Municipal Executive takes into account technical aspects, including local ones, such as epidemiological specificities and the availability of revenue, in order to optimize the use of resources to benefit the entire community, the budgetary program is grossly compromised by the attendance to individual claims. Equating the collective needs of health with the availability of public resources, as established in the budgetary choices, becomes ineffective.

Thus, the conflict between the needs of citizens and the willingness and ability that the authorities have to meet them is characterized. Due to the individualized nature of the Judiciary's actions in granting individual claims, this conflict does not translate into a debate in a broader public sphere capable of producing substantial changes in health policy - regarding its funding and scope, for instance.

Lastly, in relation to the second hypothesis raised here - that the Judiciary produces a concentrating effect due its interference in the opportunities of access to public goods - the present study does not enable us to state that higher income segments are the greatest beneficiaries in absolute terms. However, there are important indications (that may well be investigated further) that segments of the population that have a lower health risk (presumably people on higher incomes) are among the beneficiaries in a higher proportion than the general population, unlike those in high risk situations. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that a significant proportion of citizens who live in areas of high health risk, presumably in a disadvantaged socio-economic situation, who have sought and used the available means of access to the Judiciary in defence of their rights, a significant element in the construction of Brazilian democratic institutions.

However, due to the limited number of citizens benefited by the lawsuits and because of the distributive consequences of these suits, the more equal access to justice does not invalidate the idea that there is a conflict between individual rights and collective rights. The option for the former through the Judiciary conflicts with social policies' character of solidarity and redistribution, tending to produce inequalities between citizens in terms of their access to health-related goods and services.

Notes

1 An expression of the practical relevance that the so-called judicialization of health has taken on was the holding of a public hearing by the Supreme Federal Tribunal on the 27, 28 and 29 April and 4, 6 and 7 May, 2009, which brought together lawyers, public defenders, judges, teachers, doctors, health practitioners, managers and users of SUS to discuss the issue directly with the Judiciary.

2 All lawsuits were considered, except those for the year 2010, since the data were gathered in the first half of 2010.

3 This distinction is clearly made by Bobbio (1997): while equality before the law means that all men are equal before the law, and is aimed societies with castes and estates, equality of rights means the equal enjoyment of rights by those recognized as citizens.

4 Legal-academic movement whose unity is built around the understanding that constitutional norms must be applied directly and immediately, as a prerequisite for their realization.

5 Given that a democracy cannot guarantees results, even if it is the only form (if thought of in contrast to two other forms derived from the classical typology, which also includes monarchy and aristocracy) that contains the tools to periodically replace governments in the light of poor results.

6 See for example, Oliveira (2005); Maciel and Koerner (2002); Guerra (2008); Veronese (2008).

7 Held in March 1986, a year after the start of the New Republic, it was the first national health conference to have a broad participation of users, professionals and service providers. Until then, such conferences were aimed at experts and representatives of government agencies.

8 Calculated to ensure a confidence level of 95% and considering a sampling error of 5%. As the suits are filed in alphabetical order, for the choice of units to go into the sample the total number was divided by the sample number. This figure was considered the interval for the selection of suits, starting from a randomly chosen number, thus avoiding the non-random choice of the first suit. The following grant-holders took part in the data gathering, processing and organization: Mariana Ferreira (Technical Support Grant), Carina Lellis (undergraduate research scholarship) and Agata Moura Machado (undergraduate research scholarship).

9 The names of individual petitioners were not registered for the sake of confidentiality, although many of their attributes - such as gender, age, address (in this case, for the classification of social risk areas according to criteria of the Municipal Health Department) - were.

10 Many requests are for procedures already approved by SUS, but which must be carried out urgently. In other cases, the usual way to access SUS was not sought before actuating the Judiciary.

11 Similarly, a study by Borges and Ugá (2010), referent to lawsuits filed in 2005 against the Rio de Janeiro Health Department, found that non-standard drugs corresponded to half the requests.

12 The national pharmaceutical assistance policy - regulated by Ministry of Health directives - defines different financing responsibilities for the spheres of government: basic component - co-financing between the three spheres; strategic component - exclusive financing of the Union (federal government); drugs of exceptional use component - shared responsibility between the Union and states.

13 In the same lawsuit different combinations between types of medication required may occur, which was not analysed in this study, although it is an important aspect to be investigated, since it may permit the identification of the recurring associations between certain types.

14 The current Civil Process Code abolished this kind of lawsuit (http://jus.uol.com.br/doutrina).

15 "May propose a public civil action: Public Prosecution Service; Public Defender; Union, States, Federal District and Municipalities; autonomous public institutions, public corporations, foundations and mixed economy societies; the Federal Council of the Bar Association of Brazil; associations that include among their institutional purposes the protection of the environment, the consumer, the economic order, free competition, or the artistic, aesthetic, historic, tourist and landscape heritage." (http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/).

16 "The MP is an institution entrusted with defending: the legal order, the democratic regime, inviolable individual interests (so-called intrinsic to the human personality and belonging to a community) and of collective and diffuse rights (characterized by encompassing not individuals or single groups, but those who necessarily have something in common) (Machado 2008, 77; emphasis added).

17 Item V of State Law 14533/02 establishes "the right to medication, to the instruments and materials for self-administration and self-control, with a view to ensuring the greatest possible autonomy for the user". Federal Law 11347 of 27/9/2006 provides for the free distribution of medicines and materials needed for implementation and monitoring of blood glucose for diabetes patients on condition that they enrol in educational programmes for diabetics.

18 This is a federal law that provides support for people with disabilities, and establishes the judicial protection of collective or diffuse interests of these people, regulating the work of the MP. In the field of health, it establishes, in a generic way, a series of actions such as the promotion of preventive actions; the development of special programmes for the prevention of occupational and traffic accidents; the creation of a network of specialized services for rehabilitation and empowerment; the guarantee of access for people with disabilities to public and private health facilities, and their appropriate treatment therein; the guarantee of home healthcare to the non-hospitalized severely disabled; the development of health programs geared to people with disabilities etc.

19 Article 196: "Health is a right for all and a duty of the State, guaranteed through social and economic policies that aim to reduce the risk of diseases and other health issues and the universal and egalitarian access to actions and services for health promotion, protection and recovery." Article 198 defines that the actions and public health services are part of a regionalized and layered network, and make up a single system that is organized according to the following guidelines: decentralization, integral care, community participation; it also determines the form of financing of the system, with participation by the Union, states, municipalities. Article 5 deals with the rights and duties of individuals and collectives, and Article 6 defines social rights, including health.

20 These objectives are: to build a free, fair and united society; to ensure national development; to eradicate poverty and marginalization and reduce inequalities; to promote the good of all.

21 In this category we included professions or occupations such as domestic worker, builder, farmer, administrative assistant, shop clerk, hairdresser, commercial employee, seamstress, electrician, waiter, secretary etc.

22 This index is "a combination of different variables in an indicator that seeks to summarize relevant information which reflect intra-urban inequalities, pointing out priority areas for intervention and resource allocation and favouring the proposition of inter-sectoral actions" (PBH 2005, 48).

23 It is known that the fact of living in low-risk areas does not necessarily mean having a high income, given the existence of illegal occupations in "upmarket" areas. But in the absence of other data, this is a reasonable indicator of the economic situation.

24 The filing method does not separate closed cases from the others, and the records rarely contain the sentence and the defence, which are filed elsewhere. Hence, these data are deduced from the overall analysis of the lawsuits.

25 Examples of arguments: "The obligation to provide free-of-charge medicines is the responsibility of all federal units, jointly and with solidarity, without any limitation or denial of supply"; "The hypothetical fact of not having the medication or that it is not on the Ministry of Health list cannot be an impediment to its delivery, since what matters is the constitutional norm"; "There is constitutional backing to compel the State, through any of the federal units, to provide free of charge the devices that are essential for citizens' health treatment".

26 Among the items supplied are hydrolyzed milk powder, geriatric nappies, disposable syringes, compression stockings, blood glucose reagent strips, parts for infusion pumps and lancets, among others.

27 For this year, we also added the item "foodstuffs".

28 According to Directive 2982/2009, the Union must transfer a minimum of R$ 5.10 per capita per year; the state must transfer R$ 1.65; and the municipality must allocate R$ 1.65 for this level of pharmaceutical assistance.

29 Data extracted from annual financial reports of the Municipal Health Department, available at: www.pbh.gov.br. Spending on medicines for distribution to the population does not include those drugs that are purchased to be given to patients undergoing treatment in health units directly managed by the Municipality.

30 Per capita public expenditure on health includes the sum of federal and state transfers, plus Belo Horizonte's own resources, divided by the total population of the Municipality.

31 Directly, since the citizen who receives the input or service through the courts may have already received other assistance (basic or specialized appointments, nursing procedures, immunization etc). Indirectly, since the same citizen also benefits from collective actions such as health and epidemiological surveillance, which, like the abovementioned procedures, also enter the calculation of health spending in the city.

32 It is worth adding that the basic list of drugs established at the federal level can be expanded at state and municipal level, depending on decisions of the respective Executives, based on epidemiological, technical and economic criteria.

Bibliofraphical References

Barroso, L. R. 2008. Da falta de efetividade à judicialização excessiva: direito à saúde, fornecimento gratuito de medicamentos e parâmetros para a atuação judicial. In Constituição e efetividade constitucional, eds. George Salomão Leite, and Glauco Salomão Leite, 221-49. Salvador: Editora Podium.

Bobbio, N. 2004. Direitos do homem e sociedade. In A Era dos Direitos, ed. N. Bobbio. Trans. Carlos Nelson Coutinho. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier.

______, N. 1997. 3 ed. Igualdade e liberdade. Trans. Carlos Nelson Coutinho. Rio de Janeiro: Ediouro.

Borges, D. C., and M. A. D. Ugá. 2010. Conflitos e impasses da judicialização na obtenção de medicamentos: as decisões de 1ª Instância nas ações individuais contra o Estado do Rio de Janeiro, em 2005. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 26 (1): 59-69.