My SciELO

Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais

Print version ISSN 0102-6909

Rev. bras. ciênc. soc. vol.5 no.se São Paulo 2010

Structural interaction between gender and race inequality in Brazil*

A interação estrutural entre a desigualdade de raça e de gênero no Brasil

L'interaction structurelle entre l'inégalité de race et de genre au Brésil

José Alcides Figueiredo Santos

Translated by Paulo Vitor Santos RibeiroTranslation from Rev. bras. Ci. Soc., vol.24 no.70, São Paulo, jun. 2009.

ABSTRACT

This paper is guided by the theoretical notion that social divisions generate effects derived from its structural interaction. Having in mind this theoretical motivation, it estimates the gender earnings gap among white e non white (black and mixed color) groups in Brazil. All the eight Generalized Linear Models estimated, whose variables are successively included, show that the gender gap is big across both racial groups but it is bigger among whites. The investigation explores the role of the underlying context of class inequality, as well as others factors, on understanding the racial variation of the gender inequality. The study considers that the characteristics of the racial inequality in Brazil, as well as the intersection between class and race, explain the bigger gender advantage for the white man. The racial hierarchy establishes limits of variation on the gender hierarchy for the non white.

Keywords: Social divisions; Gender inequality; Racial inequality; Intersections between class, race and gender; Ernings.

RESUMO

Este trabalho é orientado pela noção teórica de que as divisões sociais geram efeitos derivados da sua interação estrutural. Tendo em mente esta motivação teórica, o autor estima a distância de gênero de renda entre os grupos branco e não branco (pretos e pardos) no Brasil. Todos os oito Modelos Lineares Generalizados estimados, cujas variáveis são sucessivamente incluídas, mostram que a distância de gênero é grande em ambos os grupos raciais, porém é ainda maior entre os brancos. A investigação explora o papel do contexto subjacente da desigualdade de classe, assim como de outros fatores, no entendimento da variação racial da desigualdade de gênero. Considera-se que as características da desigualdade racial no Brasil, assim como as interseções entre classe e raça, explicam esta maior vantagem de gênero do homem branco. A hierarquia racial estabelece certo limite de variação sobre a hierarquia de gênero no grupo não branco.

Palavras-chave: Divisões sociais; Desigualdade de gênero e raça; Interseções entre classe, raça e gênero; Rendimentos.

RESUMÉ

Ce travail est guidé par la notion théorique suivant laquelle les divisions sociales gèrent des effets dérivés de leur interaction structurelle. Ayant cette motivation théorique en vue, l'auteur estime la distance de genre de revenu entre les groupes blanc et non-blanc (noirs et métis) au Brésil. Tous les huit Modèles Linéaires Généralisés estimés, dont les variables sont succéssivement inclues, démontrent que la distance de genre est grande dans les deux groupes raciaux, mais l'est davantage entre les blancs. La recherche explore le rôle du contexte sous-jacent de l'inégalité de classe, ainsi que les autres facteurs, suivant la compréhension de la variation raciale de l'inégalité de genre. Nous considérons que les caractéristiques de l'inégalité raciale au Brésil, ainsi que les intersections entre classe et race, expliquent cet avantage accru de genre de l'homme blanc. La hierarchie raciale établit une certaine limite de variation sur la hiérarchie de genre dans le groupe non-blanc.

Mots-clés: Divisions sociales; Inégalité de genre et de race; Intersections entre classe, race et genre; Revenus.

The principles of social organization may generate consequences which go beyond its specific causal powers. The social divisions that organize durable inequalities exert joint effects resulting from their structural interaction. It is investigated, in this paper, the hypothesis that gender inequality of earnings in Brazil would be affected by racial hierarchy. To achieve this aim, as well as its theoretical motivation, it is estimated the gender earnings gap among racial groups, using new methodological solutions, and the components of inequality are analyzed within each racial group. This paper focuses on gender divisions within the divisions of race, the combination of these categories considering the specificity of mechanisms of each social division and their processes of social interaction. The undertaken analysis locates and operates, in a complementary way, the role of the underlying context of class economic inequality structure in the understanding of emerging inequality patterns. This initiative is also enrolled to a research program of greater comprehensiveness about the production and reproduction of social inequality in Brazilian society.1 The studies on inequalities of race and gender developed in Brazil serve as a support to the current treatment of the interactions among these social categories (Figueiredo Santos, 2005a and 2008).2

Gender and race have evolved as separate fields of research in the social sciences studies. The racial studies favored the non-white man and the gender studies, the white woman. This mode of study for each hierarchy separately, in isolation from one another, marginalized in both areas the study of non-white women as well as encouraged the merely additive treatment of the attributes of gender and race (Glenn, 2000, pp. 3-4). Many researches, when considering gender and race as independent factors, focus on one factor over the other. From the theoretical point of view, omitting gender or race involves assuming that the attributing of rewards is neutral concerning the factor omitted. In a statistical model, it represents a specification error because it is eliminating a relevant variable correlated with independent variables in the model, which bias the estimated effects of the correlated independent variables. Other researches, when controlling the other factor, which represents an advance, often do not test the possibility of interactions between these variables (Reskin and Charles, 1999, p. 385).

The social constructions of gender and race, although distinct, were interwoven in their historic constitution and in the individual experience. The nature and dynamics of power, of the privilege and oppression could be better understood if gender were considered in combination with race and class. Gender roles and experiences of discrimination at the workplace may vary as a function of both gender and race (Ferdman, 1999). In a sense, race and gender would be systems of social relations mutually constituted, organized around perceived differences, and not characteristic of fixed categories (Glenn, 2000, p. 9).3

In the study of the relationship between gender and race in the production of inequality, it took course the thesis of "double jeopardy", in which the person who occupies a subordinate position in more than a hierarchy would suffer the sum of the disadvantages of both dimensions. This idea, though often invoked, has not been adequately examined (Leffler and Xu, 1997, p. 71). The thesis of "double jeopardy" assumes that the effects of gender and race are additive, so that the non-white woman would suffer the full sum of the disadvantage associated to the two types of subordinate status. A review of the sociological literature on the intersection of race and gender in the labor market, with particular focus on the United States of America, suggests that the evidence collected would still be mixed, without clearly favoring one modality of interpretation, and would depend on the proposed question, on the method employed, and on the type of process investigated. Despite the ambiguity of the empirical results obtained, it is argued that focusing on the intersection between both social divisions may enrich our understanding of economic inequality and provide more accurate conceptualization of the labor market processes (Browne and Misra, 2003). The assumption of additive effects, taken as a guide or for reasons of simplicity, actually represents a very strong thesis since it is assumed that the subordinate group faces the full burden of the worst of both worlds. A more recent empirical study presents wide and robust evidence that questions the characterization of the "double jeopardy" in the U.S.A by demonstrating that women of all eighteen minority studied groups, within their respective racial or ethnic groups, suffers from a lower gender penalty than white women (Greenmar and Xie, 2008).

Investigations of the gender (or race) earnings gap must estimate adjusted means, not limiting themselves only to the comparison of the observed means since this additional procedure proved to be important to demonstrate intrinsic relationships and specify the nature of the underlying links between the variables. In the analysis of gender inequality concerning earnings in Brazil which estimates adjusted means, studies written by economists from the perspective of the "human capital" approach are predominant (Kassouf, 1998; Matos and Machado, 2006). This hegemonic paradigm in the area with influence on sociology itself underestimates the positional and relational bases of social inequality, which does not invalidate the partial contributions offered and the evidence found, although some of them need to be qualified and even reinterpreted, particularly when positional variables endogenous to the social divisions are treated as exogenous variables, such as the acquisition of educational credentials (Reskin and Charles, 1999, pp. 389-390; Figueiredo Santos, 2002, pp. 199-216 and 253-262). The sociological contribution stands out particularly in researches on racial inequality of rewards (Valle Silva and Hasenbalg, 1992; Hasenbalg et al. 1999; Telles, 2003). However, these authors do not directly model or conceptualize the possibility of interactive effects between these variables. An interactive effect occurs when the association between the independent variable of interest (gender) and the dependent one (earnings) differs in strength or shape at different levels, or categories of the race variable, with which it interacts. To the extent that race and gender interact, excluding an interaction term of the explanatory model produces inaccurate estimates of the effects of gender and race (Reskin and Charles, 1999, p. 386). The present study aims to supply a differentiated contribution in five different aspects: the introduction of the dimension of the underlying structure of economic inequality concerning the social class in the analysis of the estimated differences; exploration of the understanding that race and gender represent distinct causal mechanisms, which the consequences for the earnings vary in terms of the nature of causal nexus (direct or mediated, types of mediating factors) and their respective intensities, which has important implications for the study of joint effects; the strict explanatory modeling of interactive effects between race and gender using multiplicative terms between both variables; the use of a log-linear specification of a Generalized Linear Model to estimate the discrepancies of the conditional means; and the formulation of a theoretical interpretation of the structural interaction, or interactive effects between the divisions of race and gender in Brazil.

Contemporary studies of social stratification by color in Brazil showed that, in terms of material rewards, the striking contrast is given between white and non-white (black and mixed) people. It was generated evidence that indicates the existence of a "cycle of cumulative jeopardy" that affects the trajectory and the results achieved by non-white people. These studies highlight the role of asymmetries in educational paths and the distribution of schooling among racial groups in the processes of social mobility and the constitution of the discrepancies of earnings. Racial inequality in Brazil, when compared to the United States, has as one of its specific characteristics the small presence of non-white people at the top of the social pyramid (Valle Silva and Hasenbalg, 1992; Hasenbalg et al. 1999; Telles, 2003). Study of the intersections and interactions between social class and race in Brazil helped to demonstrate that much of the racial inequality of earnings is related to an unequal opportunity of access to valuable resources and contexts, notably the allocation to class structure, possession of educational credentials, and socio-spatial distribution (Figueiredo Santos, 2005a). The analytical distinction between unequal access and unequal treatment, as well as the correct interpretation of the meaning of both, is a key issue to understand racial inequality in Brazil. The link between social class and race, particularly strong in Brazil, derives from the importance of the processes of exclusion of control of resources that both social divisions involve. Social divisions, that overlap so strongly, emphasize the role of indirect effects and the mediating processes. The consequences of the divisions of race, when operating through the placement of non-white people in inferior positions in the social hierarchy, show the importance of race as a social category which conditions the unequal access to the valuable "positional goods" which constitute processes of discrimination concerning access or allocation.

Gender inequality in Brazil, as I argued in another study connected to the same research program, is structured with characteristics very different from race. Gender creates a much lower gross discrepancy of earnings when compared to race (32% versus 75%) however, it produces a much higher adjusted or controlled earnings differences (35% versus 13%), indicating that we are dealing with very divergent processes leading to discrepancies concerning earnings. Although there is a gender inequality concerning the access to the class structure and to the occupational order, women have important positional advantages, particularly in the control of educational credentials, and the direct effect of gender (unequal treatment) preponderate over the indirect effect (inequality of access) in the explanation of the discrepancies in earnings between men and women (Figueiredo Santos, 2008). The processes of social selectivity - which exclusionary effects may be cumulative, and which have a decisive impact on the control of "positional goods" - operate in a much stronger mode among racial divisions. Although most of the effect of race is indirect and most of the gender effect is direct, it does not mean that race is less important than gender. Racial divisions generate more pronounced and exclusionary consequences, and have been shown as more difficult to be eroded in Brazil.

Researches performed by economists interested in the theme of discrimination, focus on the comparison between combined groups of race and gender: white women, black women, white men and black men. Mattos and Machado use pooled cross-sections to analyze the presence of discrimination by sex and race in Brazil. The study uses a technique of decomposition and defines discrimination from the perspective of the traditional theory of human capital, as the earning gap that cannot be attributed to differences in skills (summarized by educational differences). When comparing earnings inequality by color, concerning the same sex, the study evidences that, besides the differential associated to discrimination, a significant part, especially for men, is due to the deficiency in the allocation of the skill attribute. In the comparison of inequality between men and women of the same color, the research noted a reduction in the earning gap when related to gender between 1987 and 2001, and what remains from this inequality is due only to factors associated with discrimination. The investigation concludes that "the inequality of labor earnings in Brazil is still a matter of gender and especially of color" (Matos and Machado, 2006, p. 23). Another study on the profile of discrimination in the labor market compares the groups with disadvantaged attributes and the white men group, taken as the standard group, which sets the norm in the labor market. Several techniques are used to analyze the earning gap due to the discrimination suffered by non-white men. It was found that black men suffer more discrimination in education and job insertion while white women suffer more from discrimination in the salary setting when both groups are compared to the white men group. The discrimination profile against black women would be "intermediate", between the black men group (based on the education and insertion) and white women group (based on the salary setting) (Smith, 2000). Cacciamali and Hirata analyze discrimination in the labor market for men and women, according to the racial group in two Brazilian States with different racial composition: Bahia and São Paulo. The research compares the probability of obtainment of earnings using a probit model with control of age and educational level into three categories that structure the labor market: executives and managers, formally hired workers and unregistered ones. In addition, the work focuses on the distinct group of poor workers, defined as those in the first quintile of the distribution of per capita familiar earnings. It was noted that gender discrimination prevails in the category of executives and managers; however, the odds of obtainment of earnings of non-white men and women, regardless of education level, are lower than those of the white group. In the group of formally hired workers, gender discrimination prevails, while in the unregistered workers group the racial discrimination prevails. Among the poor, there is gender discrimination, but racial discrimination does not present statistical significance (Cacciamali and Hirata, 2005).

Simultaneously examining gender and race can provide a relevant framework of the specific situations of the various subgroups formed from the combinations of these categories (Xu and Leffler, 1997, p. 73). However, by doing so, it is lost the demarcations between the divisions of race and gender, which represent distinct causal mechanisms and which consequences for earnings are felt through features and differentiated explanation links. The black woman in Brazil, for being a woman and black, tends to be in greater jeopardy, even if there is not a "simple sum" of the two jeopardies. However, when the overlap of race and gender is performed, as a consequence it becomes difficult to determine the independent contribution of each "component" responsible for this enormous jeopardy, the covariates associated with each of them, as well as of the factors that allow the understanding of the joint effects which may be especially problematic due to the existence of divergent processes between the two social divisions. Given the divergences found between gender and race in the jeopardy concerning gross and adjusted earnings, which are related to the predominance of indirect effects on racial inequality and the direct effects on gender inequality, it would be better to follow an analytic path that distinguishes and specifies additive effects, direct and indirect, and the interactive ones, which are effects on effects, instead of taking the merging of the two categories as a starting point.

Recent sociological studies that address the joint effects of gender and race in the production of unequal rewards perform relevant and revealing comparisons, but they do not come to model directly, with the use of multiplicative terms, the interactive effects that specify the conditions under which the effects of a variable of interest changes in strength or shape depending on the level or category of another variable with which it interacts. An investigation about the relationship between the unequal regional development, confronting the States of São Paulo and Bahia, and wage inequality related to race and gender in Brazil, showed that in 1991 the longest gender gap was found among white group. When using a traditional model of decomposition of the earnings gap, in which discrimination is the "residual" not explained by human capital endowments, the study comes to a conclusion already preconfigured by the model adopted where the white woman would be the "group that suffers the greatest wage discrimination" (Lovell, 2000, p. 291). A more recent study explicitly focuses on the coordination and cross-thematization of gender and racial-ethnic kind of determinants. The decomposition of the wage gap reveals that white women suffer more discrimination in the labor market. Black men are more penalized by unequal access to educational credentials. Among the highest positions in the labor market, however, the component of discrimination also prevails for black men. Among black women a kaleidoscope of factors of access and direct discrimination explain the wage gap compared to white men. The degree of discrimination is increasing as one moves to the top of the earnings hierarchy and it prevails for all subordinate groups (Bidernam and Guimarães, 2004).

There is still a limited empirical knowledge of the discrepancies of rewards that emerge from the interactions between gender and race. Besides this limitation, the treatment of interactions between race and gender has been performed many times in a passive way, as the evidences of interactive effects were basically empirical nuances. No attempt has been made to derive a theoretical significance for the interactive patterns found. However, the interactive effects between race and gender have information of theoretical importance that must be approached in a direct and active way (Greenmar and Xie, 2008, p. 1219). This study is part of a comprehensive research program of the major social divisions in the country, especially class, race, and gender, with a unity or convergence of theoretical orientations, measurement tools, database, and analysis strategies. The results obtained by previous researches about the specific characteristics of categorical divisions of race and gender help to clarify the terms of comparison between the categories, enlightens the divergences of processes and consequences, as well as offer a special opportunity to address the interactive effects between the two social divisions.

It is aimed to test the hypothesis that gender inequality in Brazil would not be uniform among racial groups. An appropriate specification of the causal processes in studies of gender inequality involves the incorporation of interactions between race and gender, so that the research design may allow the gender effect to differ among the racial groups, avoiding the assumption that gender inequality is equivalent between white and non-white people (Reskin and Charles, 1999, pp. 385-386). The explanations of inequality between men and women cannot be generalized automatically to white and non-white people. It was chosen the racial dichotomy between white and non-white (black and mixed color), because it is found that at this point the preponderant divisor of the racial inequality of earnings in Brazil (Valle Silva, 2000, pp. 18-19; Telles, 2003, p. 192).

This study adopts a sociological approach that emphasizes the relational, categorical and structural determinants in generating inequalities of rewards. It is not adopted in this paper the traditional solution to estimate residuals of the regression analysis after controlling the human capital factors as measures of the concept of discrimination. This practice reflects limitations particularly concerning the comparison between two different dimensions of inequality, as are race and gender, each with its own structural determinants. This kind of traditional approach - when evidencing that gender differences concerning earnings adjusted by human capital are higher than those of race - stimulates the artificial conclusion that gender discrimination would overcome racial discrimination. This conclusion is largely a result built by the very terms in which the question is put. The underlying logic behind this approach nurtures the practice which is not much theoretically and empirically consistent to treat the endogenous variables as if they were exogenous. The variables supposedly stipulated as exogenous to social divisions may account for a statistically substantial difference in earnings, particularly in the case of race. Indicators of human and social capital, however, should be treated both as results and as causes of racial and gender inequality. They are inextricably linked to the role that race and gender have been having as fundamental principles of organization of social life (Marini, 1989, pp. 361-362; Reskin and Charles, 1999, pp. 389-393).

In the treatment of interactions between gender and race, with the construction of multiplicative terms, this paper will focus on gender inequality, in view of the theoretical argument that will be developed. Without discounting the symmetrical nature of the interactive effects, it is intended to estimate the racial variation of the "gender effect". This approach has the virtue of measuring the magnitude and statistical significance of the conditional effect, i.e., the amount of the gender earnings gap in each racial group. However, it has as a limitation the fact of not performing a direct comparison between, for example, the white man and the non-white woman, or between any two groups that differ from one another both in race and gender (Greenmar and Xie, 2008, p. 1218). On the other hand, when considering the groups that contrast in both dimensions, it is confused the mechanisms and results characteristic of each social division and it is lost the distinction of gender inequality, which was the "angle" chosen to look at the interactions between gender and race.

This study also aims to address, as a preliminary step, unequal allocation or access to class structure of the combined groups of gender and race. The social structure marks a pattern of inequality between class positions. An important part of the discrepancies between these combined groups can be mediated by the access to class contexts which are unequally rewarded. The underlying context of the structure of class economic inequality helps to situate and understand the allocation components underlying to the gender discrepancies regarding earnings between racial groups.Parte superior do formulário

Distribution of groups and access to class structure

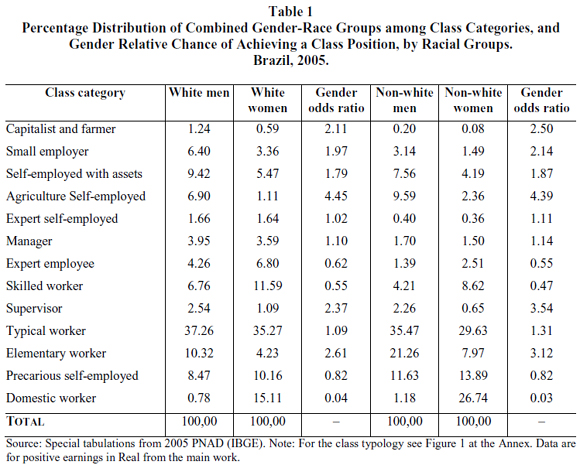

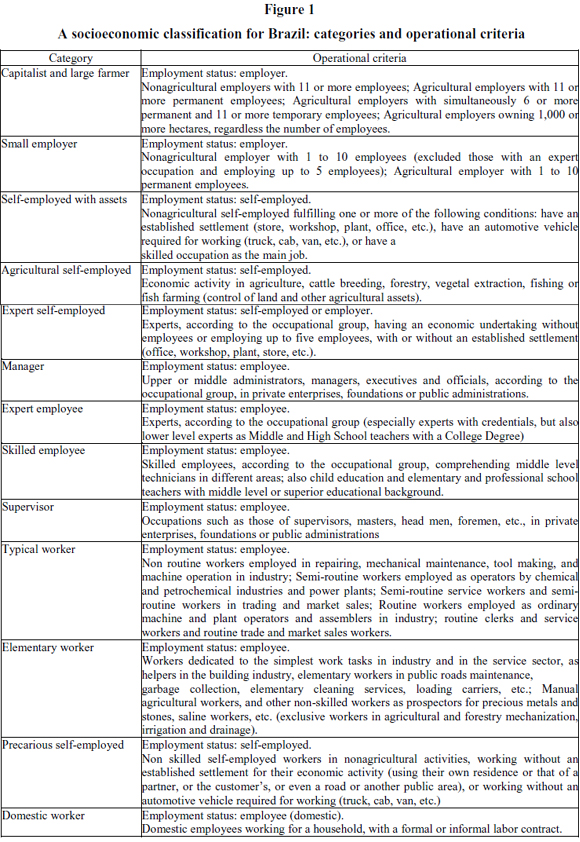

Table 1 depicts the patterns of distribution and the disproportionate access of men and women, differentiated by racial group, to the structure class positions in Brazil. The percentage distribution of gender among the categories of class makes it possible to identify a relationship, or association, between the two variables and show how gender affects access to class order. However, the comparison between groups will be performed through the use the concept of odds and the calculation of odds ratios or relative odds. An odd is the ratio between the frequency of falling into one category and the frequency of not falling into this category. This is equivalent to comparing two probabilities forming the ratio between them. The result can be interpreted as the chance of an individual randomly selected from the population to fall into the category of interest rather than in another category. In the analysis of categorical data, the "effect" of a variable on another is best expressed in terms of relative odds, which is the ratio of two odds. The odd of a category can be compared to any other. It is compared in Table 1 only the odds of gender differences in each distinct racial universe. This measure which allows the comparison of the odds, or which measures the relative odds, has a simple interpretation. When the chances of the two categories being compared are equal, the ratio will result in the value 1 (one), which is equivalent to lack of a statistical association. Values lower than 1 (one) imply a negative association, and higher than 1 (one), a positive association. The more the value is distanced from 1 (one), the greater the association (Reynolds, 1982; Rudas, 1998). In Table 1, the man (white or non-white) is the numerator of the odds ratios.

In the white group universe, men have a gender advantage of access to all positions that involve control of capital and land assets. This advantage increases with increasing of the dimension of the capital controlled. In agriculture, where more traditional gender relations predominates, men's chance of being the holder of a small agricultural activity is multiplied by 4.45 when compared to women's chance.

Among the privileged middle-class locations, there is a strong male disadvantage in access to the status of specialist employee in the white group, an almost balance to the position of self-employed expert and a small advantage to the position of authority exercised by the manager. When looking at the overall configuration of the middle class in the universe of white group, the men display access disadvantage due to the relative weight or higher density of the specialist position - which can be seen by comparing the percentages in the columns - and the fact that the odds for women are higher in this category.

Among the ambiguous class positions of skilled employees and supervisors, associations can be made in opposite directions. The odds of access significantly increase among supervisors and strongly regress among skilled employees. The situation registered in the last category reflects the educational advancement of women and the strong contingent of teachers of elementary school in this position.

When considering the bottom of class structure, it appears that white men have higher relative odds, although not much higher of being in the great aggregate of typical workers. Among the destitute class positions, in Table 1, men have more chances of occupying manual work positions than women, both agricultural and nonagricultural, that constitute the class of elementary workers. On the other hand, men have a gender advantage of being negatively associated with positions of precarious self-employed and domestic workers that get smaller rewards.

It will not be commented in this paper the allocation discrepancies between racial groups, which can be easily found by comparing the columns of percentages, since it was the subject of another study (Figueiredo Santos, 2005a). Given the focus of the present study on racial variations in gender inequality, Table 1 serves to measure the component of gender inequality of access to class unequally rewarded positions that may underlie the gender discrepancies concerning earnings and possible differences in this earnings gap when the racial groups are compared.

When the white and non-white universes are compared, it is possible to notice similarities and differences in the patterns of intersections or crossings of class and gender. Non-white men have more relative advantages of access to capital assets, and these advantages also grow according to the increasing of the controlled capital.

Among non-white, the exercise of authority represents a stronger male prerogative, particularly in the position of first line supervision. In the dimension of control of skilled assets, except among self-employed experts, being a man in the non-white universe implies a strong negative association with the positions that incorporate skill and expertise among employees.

Among the waged working-class, linked to collective forms of work, which executes a typical or an elementary work, the non-white men have strong gender advantages of access when compared to women of the same racial group. Among the destitute class positions that are self-employed or are embedded within the household domain, the relative odds of gender were quite similar in both racial universes. The racial distribution between these positions is extremely divergent: non-white are, in most of the cases, grouped among elementary workers and domestic servants. However, this analysis focuses on gender differences within each racial group. The odds ratios achieve well this goal because they represent measures of association that aim to capture inherent relationships between variables, i.e., intrinsic relations that are independent of differences between the marginal distributions of the contrasted variables.

Gender earnings gap between racial groups

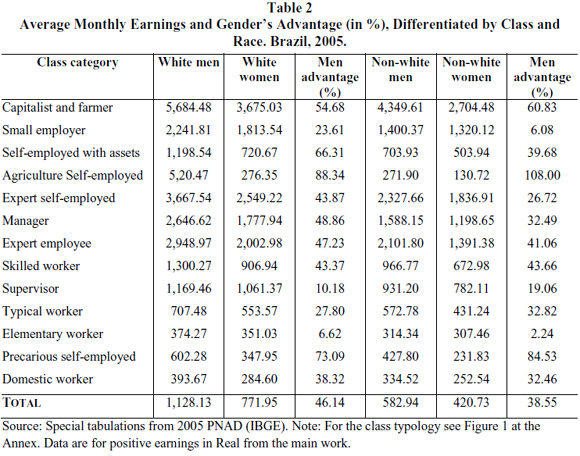

Table 2 presents data on the average earnings differences (in Brazilian currency: Real, R$) between intersections or crossing of social categories of interest, considering the need to situate the mediating role of class structure in the understanding of racial variation of gender differences in earnings. The last line of the table, where the total is displayed, shows that the male advantage of earnings, not adjusted by other variables, is higher among white men (46.14%) than among non-white men (38.55%). Furthermore, it is observed that there are actually different levels of male advantage depending on the context of class, which testifies not only the mediator role, but also the moderator of the class structure. The mediating role stems from unequal access to positions which are unequally rewarded. The moderating role of class shows itself through the fact that the gender earnings gap is enhanced or attenuated depending on the context of class, as shown by Figueiredo Santos (2008). It would then observe whether the distance from the overall average, i.e., the variation between the contexts of class, would be similar or not among racial groups, particularly among the categories of class that have a higher density in the class structure and therefore have a greater importance in the formation of the mean of the racial group. The result does not show an outstanding contrast. Among white and non-white groups the equal numbers of class contexts (six) and almost the same contexts, except for one, pull the average gender gap in earnings upward. The data indicate, therefore, a greater importance of gender inequality in the access to the class order as a factor to be considered in understanding the racial variations in gender earnings gap.

Analysis method and statistical model

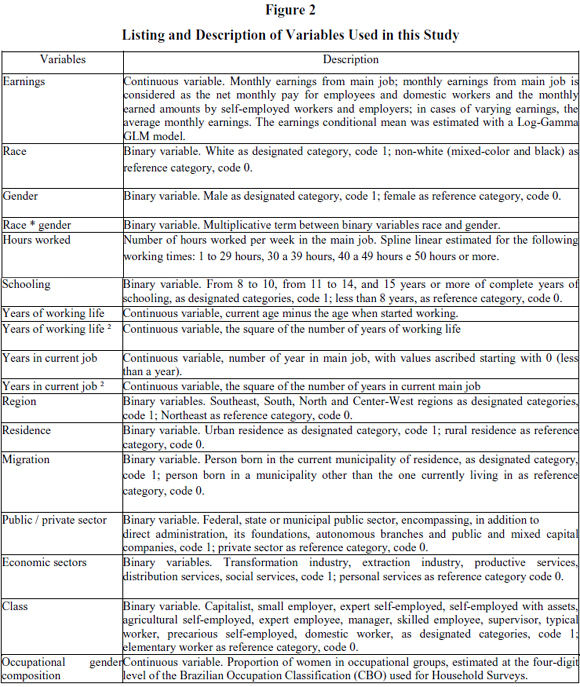

In this section, it will be specified the method of data analysis and the characteristics of the statistical model used to estimate the adjusted earnings gap. The simple confrontation of average earnings, even if relevant because it shows the gross earnings gap between the categories, does not allow to demonstrate unambiguously the "gender effect", since earnings is also associated with other variables, which must be controlled to see the variability of earnings that arises from the factor of interest. In addition, the application of a statistical model incorporates multiple variables to the analysis that act inside the original link found. This elaboration of the original relationship allows the approach of the underlying structure of the data. It will be performed a variation analysis of gender inequality of earnings in Brazil, among racial groups estimating gender gap in successive Generalized Linear Models, which includes other factors with significant impact on the earnings and may be associated to divisions of gender and race. The use of "statistical experiments" allows the knowledge of the main factors that conform, mediate and specify gender inequality, as well as the establishment of the direct effects, unmediated, of gender divisions between racial groups.

This research benefits from a new methodological proposal formulated by Professor Trond Petersen from the University of California-Berkeley, to estimate the conditional mean of an interval dependent variable, as earnings. This solution retains the interpretive advantage of estimating relative differences in the average earnings, but without the problems associated to the semi-logarithmic specification of a standard regression model. A loglinear specification of a Generalized Linear Model produces interpretations of relative differences, in terms of arithmetic mean instead of geometric means, the opposite of what occurs with the semi-logarithmic specification of the OLS regression model after calculating the exponential of the estimated coefficient, aiming its re-conversion to the original metric of the interval dependent variable (Petersen, 2006, Goodman 2006). The Generalized Linear Model has three components: a random, a systematic and a link one. The first refers to the dependent variable and the probability distribution that is associated to it. The systematic component relates to the independent variables and how they combine in order to build an explanatory model. The link component specifies how the mean of the dependent variable is related to the so-called linear predictor (explanatory model). The average can be modeled directly or some monotonic function of the mean may, then, be modeled (Agresti, 2007, pp. 66-67; Jaccard, 2001, pp. 3-4)4. This study will use the Generalized Linear Model with a logarithmic link function and a Gamma distribution. In loglinear specification of this Model, the logarithmic transformation is internalized within the model. The link function exponentiates the linear predictor instead of performing the logarithmic transformation of the dependent variable. The Gamma distribution is appropriate for dealing with positive dependent variables with constant coefficient of variation - property which shares with the log-normal distribution -, but the model is robust even in the presence of large deviations of this criterion. Modeling observations with a Gamma distribution and a logarithmic link function is a better alternative than using the standard regression with logarithmic transformation of the dependent variable, since the model requires no external transformation, retains the original information and it is easier to interpret. "Indeed," explains Hardin and Hilbe, "because the format of the two parameters of the Gamma distribution is flexible and can be parameterized to fit many response formats, it would be preferable to the Gaussian model for many situations of data with strictly positive responses" (Hardin and Hilbe, 2007, p. 90; Halekoh, 2007). All Models were estimated using the statistical program Stata, version 9.2 (Stata, 2005).

The appropriate measure of the earnings gap between contrasted categories depends on the purpose of the analysis. The earnings gap estimated in this research reflects various forms of discrimination, not only those that occur in the context of integration into the job market, but also the consequences arising out of choices and paths taken under the influence of experienced or anticipated constraints (Gunderson, 1989, pp. . 48-49). The coefficients of the log linear specification, when providing relative differences between the categories, fit well with the theoretical logic of the study of inequality. This specification also helps to correct the strong positive asymmetry of the distribution and helps to reduce the influence of outliers in the estimation.

The treatment of hours worked plays an important role in the specification of the earnings equation to estimate the gender gap. Here follows the specification proposed by the innovative methodological work of Morgan and Arthur, which avoids the underestimation of the gender earnings gap. It is recommended to use the log of earnings as the dependent variable and the log of hours worked as an independent control variable, with the equivalent return in terms of log of hours worked varying in a piecewise mode with a spline function through the range of hours worked (Morgan and Arthur, 2005, pp. 398-401). The equivalent of the first recommendation in a Generalized Linear Model would be the choice of log-link function.

The comparison among groups involving control of multiple variables in order to study interactive or conditional effects, it is sometimes done by calculating regression equations for each group separately. However, this analytical practice usually does not result in a statistical test of differences in the estimated coefficients between the two groups, when this test is necessary to make inferences about differences between the groups. The analysis conducted with the construction of interactive terms applied in this study, performs this statistical evaluation of differences between groups (Jaccard and Turrisi, 2003, p. 36). In the interactive model, the independent variable X has a conditional effect, which depends on the value of the variable Z, with which it interacts. It is estimated the effect of X on Y, given Z=0 (zero). When interactive terms are set between binary variables such as gender and race, the conditional effect on the value 0 (zero) refers naturally to the reference category (omitted) of another variable that compose the interactive term (Brambor, Clark and Golder, 2006 , pp. 73-74). The analysis of variations in the gender gap between racial groups will use the strategy of "recoding of binary variables," in which successive recalculations are made from the regression equation and the relevant statistics are produced after the specification of each reference category of interest (Jaccard and Turrisi, 2003, pp. 55-60).

Empirical research uses the micro data basis from 2005 PNAD (IBGE, 2006). The sample used in this study consists of 165,147 cases that have valid information for all variables. Due to the choice of log linear specification of a Generalized Linear Model, the analysis was restricted to cases with positive earnings. It is used only the earnings of the main job, for reasons of adjustment, since the socio-economic classification used to measure the concept of social class was built considering the main job of the person.

Gender gap variations between racial groups

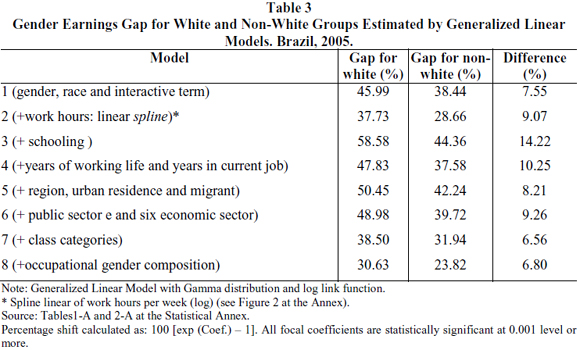

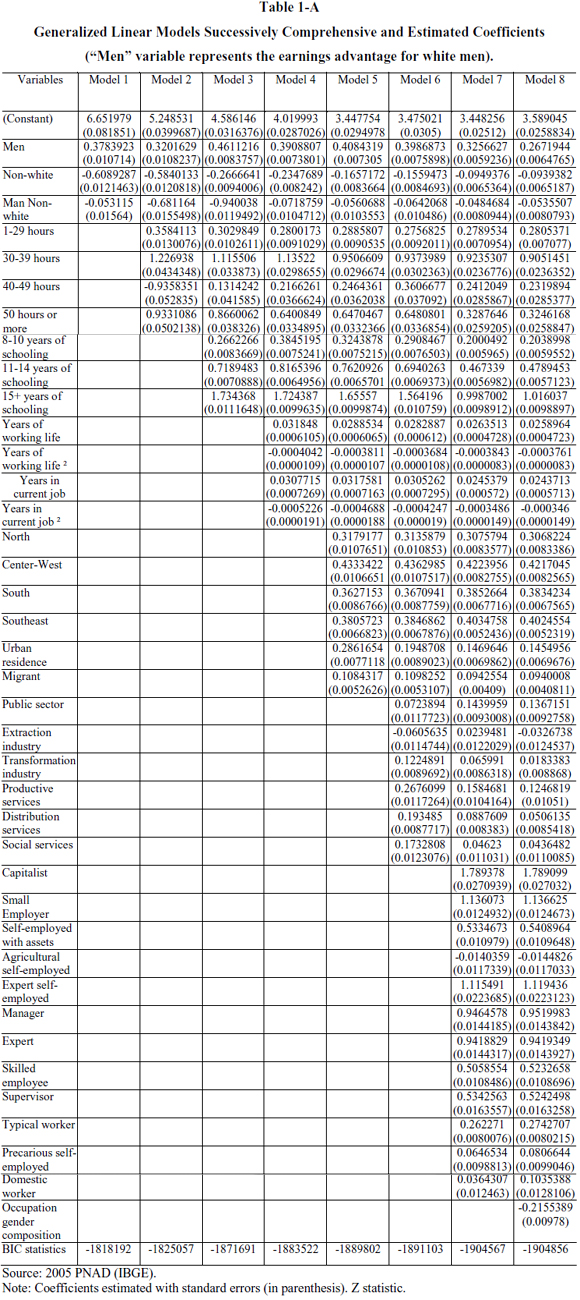

Table 3 presents the results of the estimated models already converted to percentage differences in favor of man5. Model 1, consisting only of the variables of the interactive term, shows that the gender advantage of male is not uniform across racial groups. The gender gap between the white men group supplants the one recorded on the non-white group. This revealing pattern of a higher gender penalty for white women will be kept on all models, with variations in intensity.

Model 2 controls the differences in hours worked between men and women, using a solution that avoids the underestimation of gender gap, as demonstrated elsewhere by Figueiredo Santos (2008). The inequality of hours worked between men and women reduces the gender gap in both racial groups. However, the gap is more reduced among non-white group, showing that in this group there is a greater gender divergence in the effect of hours worked, as captured by the linear spline, which generates an increase in the gender gap between the two racial universes.

Parte superior do formulário

Model 3 introduces the control of educational credentials. The effects of inequality of education between groups and the earnings differentials by educational level are controlled. In the specification of the regression model without interactive terms between educational credentials and the ascribed factor race or gender, earnings differentials by educational level were similar between the groups. It means that the effect produced by the earnings gap is due to the inequality of education found among the categories (given the existing earnings differentials by level of education). This procedure produces and reveals a very significant increase in inequality of treatment of gender in racial groups. The even stronger absolute increase in the distance between white men makes the racial gap in gender inequality reach the highest point. As the earnings gap is already in a very high level among the white, the statistical control of the educational credentials - the control of a suppressor variable that brings out the direct effect of inequality of treatment of gender - increases the absolute variation of the gender gap among racial groups, although its relative increase, compared to the percentage recorded in the previous model, shows a very small difference between racial groups6.

The control of the discrepancies of years of working life and time in the current job, shown in model 4, in which white and non-white women have disadvantages, reduces the difference between the two gaps, but this discrepancy is still at a high level. In a very simplified way, one can say that the control of the variability due to a disadvantage diminishes the earnings gap between the disadvantaged group (women) and the privileged one (men), revealing thus, the weight of the contribution of this component to the gender earnings gap. In this sense, the gender discrepancies in relation to these factors appear to be greater among white people because there is a greater decrease both absolute and relative to the gender gap.

The controls of the circumstances of geographical location, household and migration conditions, carried out in model 5, increase the gender gap in both racial groups, but this process occurs more strongly in the non-white group, which precipitates a reduction in their racial variation. This result shows that the urban and regional distribution gives a slight relative advantage to the women in the non-white group when confronted to the non-white men, because its statistical control causes further increase the gender gap in this racial group.

From model 6, socioeconomic variables are introduced. They are related to the social division of labor and are typically structural in nature. Model 6 makes the divergence in the gender gap increase. Gender inequality in access to economic sectors, in which there are different patterns of average earnings, is higher among the non-white group, since the control of this mediating component of inequality generates a greater reduction in inequality of earnings in this racial group, which produces the increase of its discrepancy between the racial groups.

The introduction of the class categories, in model 7 reduces the discrepancy between the gender gap to its lowest level. This means that the asymmetrical access to class positions, which are unequally rewarded, plays a key role in explaining the existing divergence. First, it is necessary to uncover the kind of earnings gap that is estimated in this model. It is controlled the differential distribution of men and women between the class positions within each racial universe, and the discrepancies in payment between the positions of class. Unequal access to the class order between men and women seems to be greater within the white universe, because of the control of the intersections between class and gender, in each racial group, approximate the gender earnings gap between white and non-white groups due to the fact that gender gap decreases more in the white group at both the absolute and relative levels. The strong component of unequal access to valuable resources, which is associated to racial oppression, possibly accounts for a smaller class differentiation among non-white men and women.

Finally, model 8 incorporates an indicator of occupational and work-type gender segregation, which is the proportion of women in each of the 519 occupational groups of the PNAD. The control of the existing occupational and work-type gender segregation within the categories of social class - the allocation between the class positions have been statistically controlled in the previous model - has a major impact on the gender gap, but slightly increases their divergence between racial groups. Note, then, that the difference between racial groups is most often associated with large aggregates of the class structure, since the internal component of occupational and work-type segregation, despite its importance as a mediating factor of gender inequality in both racial groups, represents only a slight relative disadvantage of non-white women, indicated by the fact that the male advantage decreases more in the non-white group.

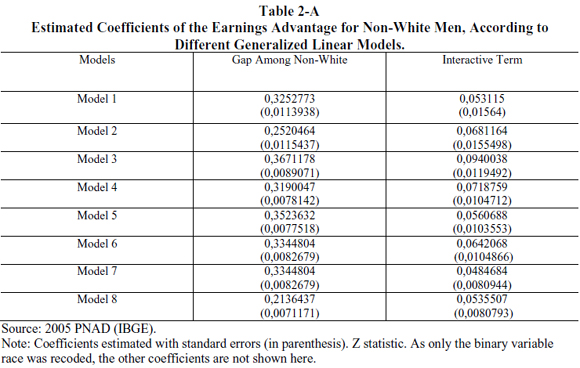

Alternative method: the effect contained in the interactive term

An alternative methodology to analyze and present the interactive effects between gender and race on earnings was proposed and used by Yu Xie and Emily Greenmar (2008). After presenting a critical review of the thesis of "double jeopardy" in North-American literature, as well as the strategies developed to study the joint effects of race and gender, the study offers a model of empirical research, using what would be, in the authors' point of view, a new and less restrictive concept of their effects. In this approach, the coefficient of main interest in the regression equation is the one formed by the interaction term between race and gender variables. In order to properly understand the meaning of the value captured by the interactive term, it is important to pay attention to the fact that it does not strictly represent the magnitude of an effect, as the coefficients of the variables that compose it do, but it express itself essentially how an effect changes, i.e., it corresponds to an effect on another effect (Kam and Franzese, 2007). The study developed here is closely related to this methodology, differing more in the way that data is presented, since the racial variation of gender coefficient between racial groups stems precisely from the magnitude and sign (positive or negative) of the interactive term, which estimates how the effect of race changes the gender effect or, symmetrically, how the effect of gender changes the race effect 7.

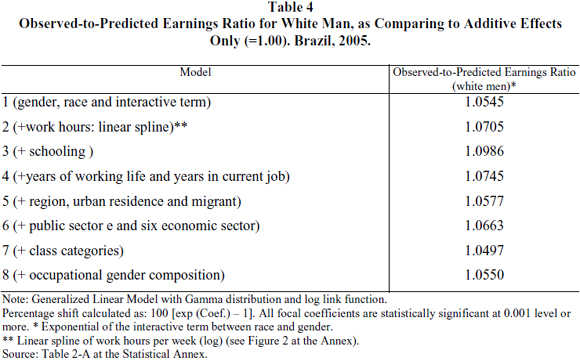

In the interactive model built here to apply this alternative method, race is included as a binary variable that takes the value 1 for the white person. Gender is included as a binary variable that takes the value 1 for men. It was generated, then, a multiplicative or interactive term between the variable of race and gender. The coefficient of interactive term represents the extent to which the membership of the white racial group has a different effect for men compared to women, or alternatively, the extent to which being a man has a different effect for members of the white group in relation to the members of the non-white group. The exponential or antilog of the coefficient of the interactive term, in the coding applied in this research, can be thought of as an observed/predicted or expected earnings rate from the white man, where the predicted earnings is based on the assumption of additive effects (no interaction) between race and gender variables. The Generalized Linear Model used in this study exponentiates the linear predictor. The U.S. researchers use a standard regression model with logarithmic transformation of earnings. A positive value of the coefficient corresponds to the exponential higher than 1, while the negative value corresponds to a value inferior to 1 (Green and Xie, 2008). The coefficient exponential value 1 is equivalent to the absence of interaction between variables, i.e., the coefficient of race does not affect the gender and vice-versa. This form of presentation has the merit of highlighting the significance of the interaction term in a simple and clear mathematical way, as a positive or negative discrepancy in relation to the neutral value 1 (one), reflecting the absence of interaction.

Table 4 shows the estimated coefficient exponential of the interactive term, which gives the observed earnings rate compared to the predicted for the white man. The values of the coefficient exponential, in the various statistical models, indicate that the average earnings of the white man range from 5.0% (model 7) to 9.9% (model 3) more than it would be predicted under the assumption of additive relations between race and gender variables. The discrepancy between the observed and predicted earnings for the white man shows that the white man benefits from an additional gain of gender when compared to the non-white man.

Greenmam and Xie (2008) noted the existence, in North-American society, of a greater gender penalty for white women, compared to all other racial and ethnic groups. In the interpretation of this result, the focus turned to the role specialization, based on neoclassical economics, whose theoretical model links inequality in the workplace to the gender inequality within the family. The authors found some evidence suggesting that within the white families there would be a higher role specialization than in families of other racial groups. This means that the white woman in the United States, from this approach point of view of role specialization, would have a higher gender penalty in their individual earnings since the familiar context, particularly of white couples with children (different from that of the non-white women), would indicate an "economic rationality" derived from this advantage of group, associated to the specialization of roles between men and women within labor division and sharing of family earnings, even if the woman has, in this specialization, a subordinate individual role in the job market. The methodological convergence between the two studies, however, does not prevent the existence of an important theoretical divergence in the interpretation of the results obtained despite the evidence presented by both articles contradict the additive assumptions inherent to the proposition of double jeopardy. This article, when looking into the Brazilian data, fits in a sociological orientation located within the Marxist tradition in social sciences and adopts a distinct line of interpretation.

Theoretical significance of the interaction between gender and race

The notion of structural limitation helps to clarify the apparent paradox underlying the smaller gender penalty suffered by a racially privileged group, which occurs as a consequence of the interaction processes between social determinants. Erik Olin Wright introduced the notion of "mode of determination" in order to emphasize the plurality of causes within the Marxist theory. The structural limitation would be, then, a mode of determination in which a structure or process sets limits of variation in another structure or process (Wright, 1980 and 1981). The interpretation of the results highlights the form assumed by the process of structural interaction between social hierarchies and the characteristics of racial inequality in Brazil. First, it should be understood that the hypothesis of "double jeopardy" reflects a "confined" view of the structure of inequality, because it assumes that inequality in a hierarchy does not generate consequences for inequality in the other hierarchy. The person in a subordinate position in the two hierarchies would suffer, then, the full effect of both inequalities. The non-additive or interactive relationship assumes the possibility of a social hierarchy to condition the effect of another hierarchy: interaction is precisely equivalent to an effect on another effect. The form of this conditioning can be thought of as an embarrassment of asymmetry that can be produced by another hierarchy. Second, there is a very big racial disparity of earnings in Brazil, as can be seen in the gross racial gap. Likewise, non-white men and women suffer from a huge component of unequal access to valuable resources and contexts, which characterize racial inequality in Brazil. This accentuated racial oppression would be able to hinder, to some extent, the variation that can be produced by other attributes such as gender within the non-white group, which is subordinated in the racial dimension. A similar process was observed in the study of interactions between class and race in Brazil, which demonstrated the existence of a lower class inequality among non-white people compared to white people. The structural interaction between class and race takes an especially restrictive sense when the class exploitation limits the racial inequality within the working class, and especially in its poorest segment (Figueiredo Santos, 2005a). When the differences in valuable contexts and resources, which are the foundation of racial inequality in Brazil, are controlled, the racial variation between the gender gap of earnings recedes to a lower level. The explanation, in Brazil, to the biggest gender advantage of the white man, equivalent to the smallest advantage of the non-white man, is rooted in the characteristics of racial inequality. The common weight of racial oppression of non-white men and women would leave a smaller space for the performance of the causal asymmetry associated to the attribute of gender. The racial hierarchy would establish a certain limit to the variation to the hierarchy of gender. The main part of the effect of race on gender discrepancy is mediated by the unequal allocation of racial groups in the class structure. The racial variation of gender gap of earnings, as demonstrated, reaches its lowest amount (6.56%) when there is statistical control of the categories of social class. The underlying structure of economic inequality of class reveals an important mediating factor in the constitution of the patterns which emerge from the interactions between race and gender. In a general scenario for high gender advantage in favor of men, the lowest gender penalty faced by non-white women, because of certain social compression introduced by racial oppression, should not obscure the fact that these women experience a strong inequality of access to the contexts of class unequally rewarded. The dimension of skill and expertise allowed advancements of class for women in their non-white racial world. However, the advantage gained by non-white women in relation to the men of the same color, in the access to privileged positions of the middle class, seems to be contradicted by a stronger relative distribution among the poorest positions, which have a much greater social density. Among non-white women, it should be remembered that racial division remains as a barrier much more difficult to overcome than gender inequality. In fact, all non-white people (men and women) are at a clear disadvantage in class order.

REFERENCES

AGRESTI, Alan. (2007), An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. 2. ed. Hoboken, John Wiley & Sons.

BRANBOR, Thomas, CLARK, William Roberts and GOLDER, Matt. (2006), Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analysis. Political Analysis, Vol. 14, nº 3: 63-82.

BIDERMAN, Ciro and GUIMARÃES, Nadya Araújo. (2004), Na Ante-sala da Discriminação: o Preço dos Atributos de Sexo e Cor no Brasil (1989-1999). Estudos Feministas, 12(2): 177-200.

BROWNE, Irene and MISRA, Joya. (2003), The Intersection of Gender and Race in the Labor Market. Annual Review of Sociology, 29: 487-513.

CACCIAMALI, Maria Cristina and HIRATA, Guilherme Issamu. (2005), A Influência da Raça e do Gênero nas Oportunidades de Obtenção de Renda: uma Análise da Discriminação em Mercados de Trabalho Distintos: Bahia e São Paulo. Estudos Econômicos, vol. 35, nº 4: 767-795.

DUNTEMAN, Gerge H. and HO, Moon-Ho R. (2006), An Introduction to Generalized Linear Models. Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, nº 145. Thousand Oaks, Sage.

FIGUEIREDO SANTOS, José Alcides. (2002), Estrutura de Posições de Classe no Brasil: Mapeamento, Mudanças e Efeitos na Renda. [Structure of Class Positions in Brazil: mapping, changes and effects on earnings]. Belo Horizonte/Rio de Janeiro, Editora UFMG/Iuperj.

_________. (2005a), Efeitos de Classe na Desigualdade Racial no Brasil. Dados - Revista de Ciências Sociais, vol. 48, nº 1: 21-65. [Class Effects on Racial Inequality in Brazil. Dados. Special English Edition 2, 2006. http://socialsciences.scielo.org/pdf/s_dados/v2nse/scs_a05.pdf].

_________. (2005b), Uma Classificação Socioeconômica para o Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, vol. 20, nº 58: 27-49. [A Socioeconomic Classification for Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais. Special English Edition 2, 2006. http://socialsciences.scielo.org/pdf/s_rbcsoc/v2nse/scs_a04.pdf].

_________. (2008), Classe Social e Desigualdade de Gênero no Brasil. Dados - Revista de Ciências Sociais, vol. 51, nº 2: 353-402.

FERDMAN, Bernardo M. (1999). The Color and Culture of Gender in Organizations: Attending to Race and Ethnicity, in POWELL, Gary N. (editor). Handbook of Gender and Work. Thousand Oaks, Sage.

GLENN, Evelyn Nakano. (2000), The Social Construction and Institutionalization of Gender and Race, in FERREE, Myra Marx, LORBER, Judith, HESS, Beth B (editors). (2000), Revisioning Gender. Walnut Creek, Altamira Press.

Goodman, Leo. (2006), A New Way to View the Magnitude of the Difference Between the Arithmetic Mean and the Geometric Mean, and the Difference Between the Slopes When a Continuous Dependent Variable is Expressed in Raw Form Versus Logged Form. Working Paper, University of California, Berkeley, Department of Sociology and Department of Statistics.

GREENMAM, Emily and Yu, XIE. (2008), Double Jeopardy? The Interaction of Gender and Race on Earnings in the United States. Social Forces, Vol. 86, nº 3: 1217-1244.

GUNDERSON, Mortley. (1989), Male-Female Wage Differentials and Policy Responses. Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 27, nº 1: 46-72.

HARDIN, James W. and HILBE, Joseph M. (2007), Generalized Linear Models and Extensions (2ª ed.). College Station, Stata Press.

HASENBALG, Carlos, VALLE SILVA, Nelson do and LIMA, Márcia. (1999), Cor e Estratificação Social. Rio de Janeiro, Contra Capa.

IBGE. (2006), Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios - 2005. Microdados. Rio de Janeiro, IBGE.

JACCARD, James (2001), Interaction Effects in Logistic Regression. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage (Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, nº 07-135).

JACCARD, James and TURRISI, Robert. (2003), Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression (2ª ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage (Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, nº 07-072).

KAM, Cindy and FRANZESE JR., Robert J. (2007), Modeling and Interpreting Interactive Hypotheses in Regression Analysis: a refresher and some practical advice. Michigan, Michigan Press.

LEFFLER, Ann and XU, Wu. (1997), Gender and Race Impacts on Occupational Segregation, Prestige, and Earnings, in DUBEK, Paula J. and BORMAN, Kathryn (ed.). Women and Work: a Reader. New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press.

LOVELL, Peggy A. (2000), Race, Gender and Regional Labor Market Inequalities in Brazil. Review of Social Economy. Vol. LVIII, n. 3: 279-93.

MARINI, Margaret Mooney. (1989), Sex Differences in Earnings in The United States. Annual Review of Sociology, n.15: 343-380.

MATOS, Raquel Silvério and MACHADO, Ana Flávia. (2006), Diferencial de Rendimento por Cor e Sexo no Brasil (1987-2001). Econômica, Rio de Janeiro, V. 8, Nº 1: 5-27.

MORGAN, Laurie a. and ARTHUR, Michelle M. (2005), Methodological Consideration in Estimating the Gender Pay Gap for Employed Professionals. Sociological Methods & Research, Vol. 33, nº 3: 383-403.

PETERSEN, Trond. (2006), Functional Form For Continuous Dependent Variables: Raw Versus Logged Form. Working Paper, University of California, Berkeley, Department of Sociology.

RESKIN, Barbara F. and CHARLES, Camille Z. (1999), Now You See'Em, Now Don't: Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in Labor Market Research, in Irene Browne (ed.), Latinas and African American Women at Work: Race, Gender and Economic Inequality. New York, Russell Sage Fundation.

REYNOLDS, H. T. (1982), Analysis of Nominal Data. Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, nº 007. Beverly Hills, Sage.

RUDAS, Ramás. (1998), Odds Ratios in the Analysis of Contingecy Tables. Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, nº 119. Thousand Oaks, Sage.

SOARES, Sergei Saurez Dillon. (2000), O Perfil da Discriminação no Mercado de Trabalho - Homens Negros, Mulheres Brancas e Mulheres Negras. Texto para Discussão Nº 769. IPEA, Brasília.

STATA. (2005), Stata Base Reference Manual, Release 9, Vol. 1-3. College Station: Stata Press.

TELLES, Edward. (2003), Racismo à Brasileira: Uma Nova Perspectiva Sociológica. Rio de Janeiro, Relume Dumará .

VALLE SILVA, Nelson do. (2000), A Research Note on the Cost of Not Being White in Brazil. Studies in Comparative International Development, vol. 35, nº 2: 18-27.

VALLE SILVA, Nelson do. and HASENBALG, Carlos. (1992), Relações Raciais no Brasil Contemporâneo. Rio de Janeiro, Rio Fundo.

WRIGHT, Erik Olin. (1980), Class and Occupation. Theory and Society, Vol. 9: 177-214.

WRIGHT, Erik Olin. (1981), Classe, Crise e Estado. Rio de Janeiro, Jorge Zahar.

Annexes

Statistical Annex

* This study had a primary research assistance of Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG, and a supplementary assistance of Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq. The author is grateful to Professor Trond Petersen from the Department of Sociology at University of California-Berkeley, for the opportunity of knowing his innovative methodological work which grounds the choice of the statistical model used in this investigation. This study also included the participation of three scientific initiation scholarship students: Lara Cruz Correa, Juliana de Souza Barbosa e Eder Lima Moreira, who collaborated in handling the data of this research.

1 This program explores the effects of the divisions of class, race and gender, as well as their intersections and interactions in the production of inequality. The socioeconomic classification for Brazil is used as an analytical tool that enhances the typology used in the book Estrutura de Posições de Classe no BrasilStructure of Class Positions in Brazil] (Figueiredo Santos, 2002). The theoretical basis of its empirical categories was previously formulated in another study (Figueiredo Santos, 2005b).

2 Considering the studies already developed and the current interest in the conditional relationships between these categories, the theoretical position of these sociological concepts will not be repeated in this paper. The recapitulation of empirical manifestations of inequality in Brazil organized around these categories will occur only when necessary.

3 It is not assumed in this paper the thesis that gender would be inherently constituted by race. Here, it is explored the effects of interaction between these categories.

4 The logarithmic transformation, of extensive use, is part of the Family of monotonic transformations that preserves the underlying order of the transformed variable.

5 Although the main interest of this study is to estimate the partial coefficients which capture the interactive effects, Table 1-A, from the Statistical Annex provides the BIC statistic, used to compare models. The best fit model is one that records the lowest value. As this statistic often has a negative value, the model with the largest negative value would be preferable (Hardin and Hilbe, 2007, pp. 56-8).

6 In the shift from model 2 to model 3, a greater absolute increase of the percentage discrepancy occurs among whites, 20.85% against 15.70% among non-white people, which explains the expansion of racial divergence. However, the relative increase in the earnings gap, in relation to the previous level, differs very little between the racial groups. Among non-white people, the distance is multiplied by 1.548, going from 28.66% to 44.36%, whereas the distance between the white people is multiplied by 1.553, going from 37.73% to 54.58%. The female advantage in the control of educational credentials, within their racial group, is higher among non-white people when computed in terms of average of complete years of study. The non-white woman has an average of 7.565 against 5.999 years of schooling of the man, which gives an advantage of 1.566 years, whereas the white woman has an average of 9.538, versus 8.154 years of the man, which creates an advantage of 1.414 (data for people with positive class position and earnings).

7 The study of Xie and Greenmar presents an instructive representation and mathematical demonstration of the divergence between the additive and interactive effects. The authors model the interactive effects by introducing interactive terms in the regression equation. The convergence between the approaches is clear, for example, when they summarize the methodology in order to examine the relationship between the determination of earnings of race and gender: "For each racial or ethnic group k, we compute the quantity d, which represents the difference between the earnings and gender gap of the minority and whites (Greenam and Xie, 2008, p. 1225).